This post contains potentially disturbing content.

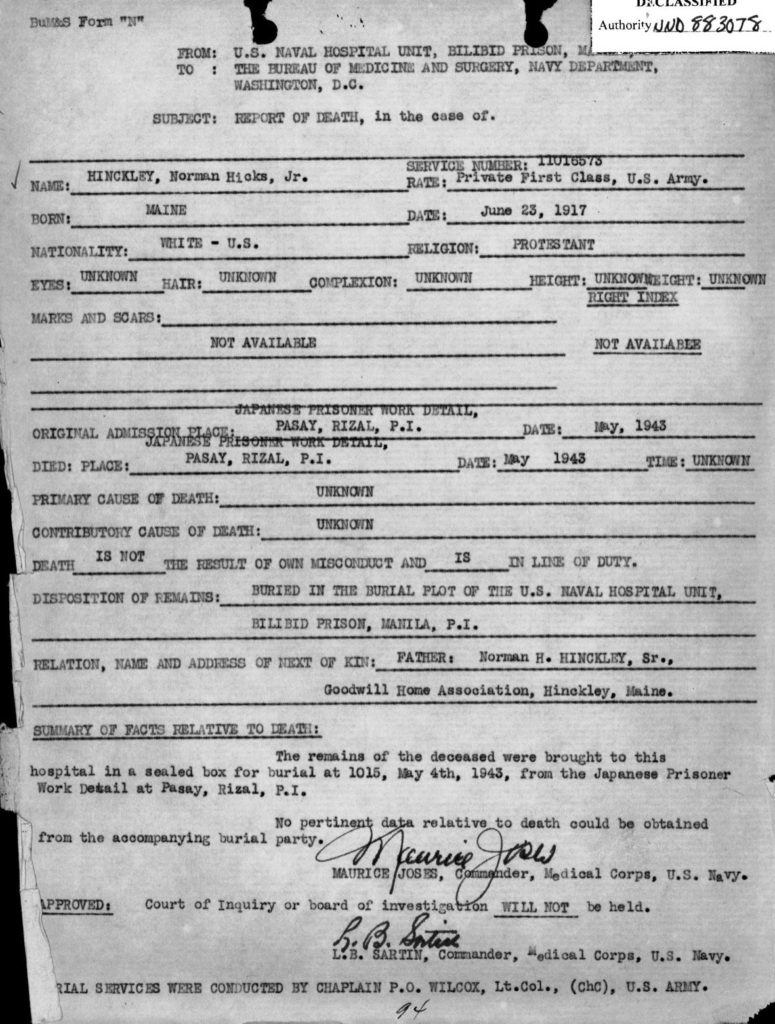

At 10:15 in the morning of May 4, 1943, the American naval hospital unit at Bilibid Prison, just outside of Manlia in The Philippines, was visited by a Japanese burial party. They had with them a sealed box, which contained the remains of 26-year-old PFC Norman Hicks Hinckley Jr.

But if the American’s wanted any details of PFC Hinkley’s cause of death, they were disappointed. “No pertinent data relative to death could be obtained” from those mid-morning visitors. An American chaplain conducted a burial service, and PFC Hinckley was laid to rest in the U.S. naval hospital’s burial plot.

And, per standard practice, a report of death was made. The only death information provided to the U.S. Navy medical bureau–and likely to Hinckley’s family–was that his cause of death was “Unknown.”

But was that the truth? Was it really possible that no one knew how Hinckley had died?

A young man’s rapid demise

On September 16, 1940–over a year before the Pearl Harbor attack pulled America into WW2–a 23-year-old Norman Hicks Hinckley Jr. enlisted as a private in the U.S. Army. He was 5’7″, 146-pounds, and fit enough to be admitted to the army’s Air Corps.

Yet two and a half years later, he was described as an emaciated, sick prisoner of war in The Philippines. And his strong will to survive was at a breaking point.

What could have happened to bring him to such a point? And could the full story of Norman Hinckley’s demise ever come to light?

A long way from rural Maine

Hot, tropical Manila is a long way from the lakes and green hills of southern Maine, where Norman Hicks Hinckley Jr. grew up.

He was born June 23, 1917, in Waterford, Maine (population 765), the only son of Norman and Rosalie Hinckley. Rosalie immigrated from Belfast, Ireland, to the US in 1910. She married Norman Hinckley Sr. in 1914. Their first child, a daughter named Charlotte, was born about a year later. In 1919, the youngest Hinckley, a daughter called Rosemary, joined the family.

In 1917, Norman Sr. worked as a storekeeper at the Good Will Farm, a home for orphaned and other struggling boys, in Hinckley, Maine. And Norman Jr. spent his early years in the nearby areas.

Air corps, infantry, surrender, and the Bataan Death March

Private First Class Norman Hinckley was assigned to the Air Corps’ 17th Pursuit Squadron, 24th Pursuit Group, V Interceptor Command. The 24th Pursuit Group was activated in The Philippines in August 1941.

Japanese aircraft attacked the Philippines four months later, on December 8, 1941–mere hours after attacking Pearl Harbor. Within a couple days, the 24th Pursuit Group’s fighting strength was reduced to one third its initial size.

By month’s end, the majority of the 24th Pursuit Group’s personnel joined the US Army 71st Infantry to defend the Bataan Peninsula. US forces on Bataan surrendered to the Japanese four months later on April 9, 1942.

While records we’ve uncovered so far don’t specifically state that PFC Hinckley joined the 71st Infantry forces, it’s likely that he did. Thus, when the Americans on Bataan surrendered, he would have endured the infamous Bataan Death March–80 miles across the hot, humid Luzon island with little food, water, or rest.

He was reported as a POW to the Red Cross on May 7, 1942.

A year enduring an “inhuman hell hole”

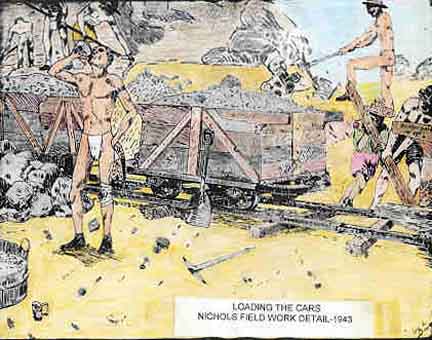

Hinckley seems to have been one of the first POWs sent to the Nichols Field work camp near Manila in July 1942. He and fellow POWs labored under strenuous, brutal conditions to level hills and build runways by hand. Hinckley “endured this inhuman hell-hole,” Alma Salm reported, “tenaciously willing himself to live for almost a year before being ordered by the doctor back to [Cabanatuan’s] Number One prison [camp] 80 kilometers away on the hot, treeless plain.”

“After a few weeks respite at Cabanatuan,” Salm continues, “volunteers were called up for another out-of-camp detail. Hinckley, poor devil, was hungry. Hoping there was more opportunity to forage for food on some of these distant details, he volunteered. It was not until his arrival at Manila the prisoner learned their destination—Nicholas Field. And when those corrugated iron prison walls again loomed before Hinckley—that did it! Overnight his face took on the ghostly paleness of a man who was long overdue to distant parts.”

The timeline is a bit difficult to figure out, but it seems that PFC Hinckley returned to Nichols Field in early 1943. Salm described the 25 year old: “Tall he was and spare, with wasted body and ulcerous arms and legs.” And despite his dismay at being returned to Nichols Field, he had a “superb determination not to die—[a] way of hurdling and conquering so many obstacles.”

“He took every epidemic that struck camp and somehow survived. It was true after each sickness he was a little more emaciated but as he sort of apologized once with a grin, ‘My damn sense of curiosity—just wondering what is going to happen next—somehow keeps me ticking.‘ ” But, Salm continues, “As I watched him during these last months I saw that fine spirit of his was noticeably wearing thin and his courageous philosophy was no longer of any help.”

The truth about Hinckley’s death

The Japanese reported that they didn’t know the cause of Hinckley’s death.

However, the truth is that Hinckley’s barbaric demise was witnessed by dozens, if not hundreds, of Japanese and Americans. And Alma Salm recorded it in his memoir–perhaps the only existing document detailing the death of Norman Hinckley.

Image 4. Veranda of Pasay Elementary School where Norman Hinckley was housed while at Nichols Field. It was possibly to one of these pillars that Hinckley was bound during his last days of life. Photo taken by Al McGrew. View more images of Pasay Elementary School.

Enduring malignant malaria and dysentery, [Hinckley] had labored among the [Nichols Field] pits day in and day out until he was no longer physically able to be a companion to a pick and shovel.

The American doctor in camp had grouped Hinckley with our sick; but the “Wolf,” our fiendish Jap slave driver, would obstinately wave the ill man out each morning to the labor battalion where his detail now consisted of boiling our drinking water and brewing tea for the Japanese guards….

Each day saw Hinckley’s gaunt figure at his task, a little more somber and detached. Then one evening he was not among the marching slaves as they returned from the pits. The following morning as the prisoners assembled in the quadrangle, Hinckley’s exhausted and abused form greeted us form the sala above. He had been apprehended out of bounds on the airfield and after the usual beatings by the Japs was lashed to one of the pillars.

In this condition he remained under sentence of death. That evening upon our return he was still there. He had been given no water nor rice since the previous day and his active dysentery had caused numerous defecations which ran down his legs and added to his misery. It was a ghastly sight, Oh God!

Sometime during the night, guided by a candle of stars overhead Hinckley’s soul quietly left us. (Salm Memoir, pages 1-3)

Hinckley would have turned 26 the next month.

And what about this sealed box?

On May 4, 1943, PFC Norman Hicks Hinckley Jr.’s remains were brought in a sealed box to the U.S. Naval Hospital unit at the Bilibid Prison near Manila.

A sealed box? What exactly was the state of Hinckley’s remains?

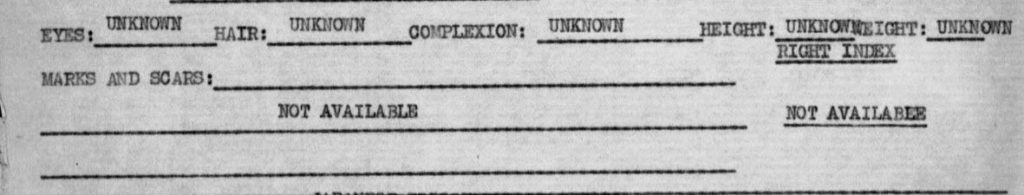

The American Report of Death offers some clues:

Notice that Hinckley’s eye color, hair color, complexion, height, weight, and scars or marks are all listed “Unknown.” This suggests that the person filling out the form couldn’t tell these things from the state of Hinckley’s remains. And perhaps more telling–in the spot designated for the right index fingerprint, typed text states “Not Available.” (Scroll to very bottom of this post for the full report of death.)

Had Hinkley’s body been cremated? Possibly. What seems certain is that the state of Hinckley’s remains did not allow the Americans to determine how he had died.

PFC Hinckley’s legacy

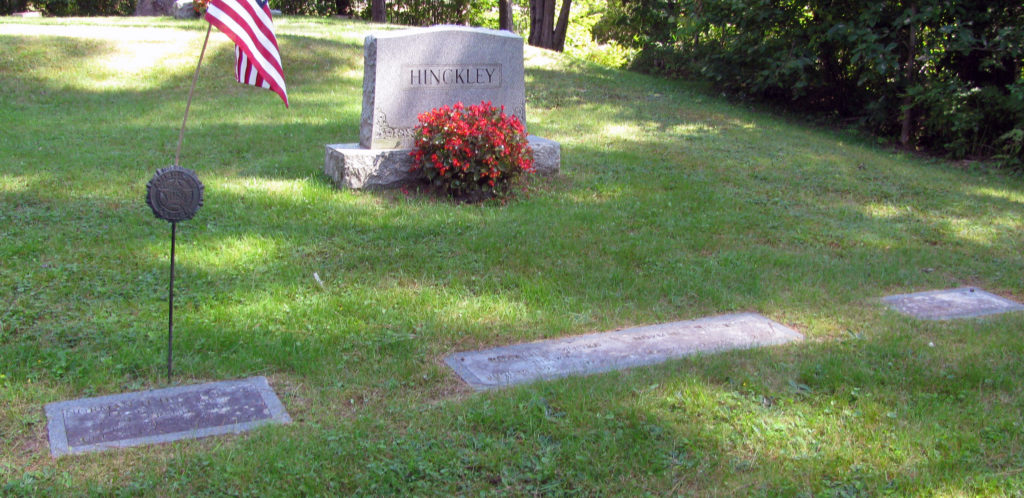

PFC Hinckley’s father, Norman Sr., died in the 1970s. His mother, Rosalie, passed in 1983. His older sister, Charlotte, died in 2000; she never married and never had children as far as we can find.

All three are interred at the Hinckley Home Farm School Cemetery in Hinckley, Maine. Next to them is a grave marker for PFC Norman Hinckley.

Norman’s younger sister, Rosemary, passed away at age 97 in 2017. She was survived by her 2 sons (who are PFC Hinckley’s nephews), 2 grandchildren, 2 great-grandchildren, and 2 great-great-grandchildren. Rosemary and her husband are also buried in Hinckley Home Farm School Cemetery.

Read next

- Learn more about Nichols Field and Pasay Elementary School, the prison camp where Hinckley spent most of his time as a POW.

- Salm began his memoir with his account of and tribute to Hinckley. Read the full text.

Help us honor PFC Hinckley

Sharing PFC Hinckley’s story with others keeps his service and sacrifices alive in our memories. Please consider sharing this post on social media or with anyone who would appreciate knowing his story. Thank you.

Sources

- “World War II Prisoners of the Japanese, 1941-1945,” database online, entry for Norman H Hinckley Junior, Ancestry.com, accessed 16 Oct 2011.

- “US World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946,” database online, entry for Norman H Hinckley, Ancestry.com, accessed 18 Oct 2011.

- “Maine Birth Records, 1621-1922,” database online, entry for Norman H Hinckley, Ancestry.com, accessed 19 Oct 2011.

- “1920 US Federal Census,” database online, entry for Norman H Hinckley family, Ancestry.com, accessed 19 Oct 2011

- Marriage Record of Norman H Hinckley and Rosalie A Moore, database inline, Maine Genealogy website, accessed 19 Oct 2011, http://www.mainegenealogy.net/individual_marriage_record.asp?id=469986.

- “WWI Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” database online, entry for Norman Hicks Hinckley, Ancestry.com, accessed 19 Oct 2011.

- “One Man’s Vision: The History of Good Will-Hinckley,” Good Will-Hinckley website, accessed 25 June 2013, http://www.gwh.org/AboutGWH/History.aspx.

- “24th Pursuit Group,” Wikipedia, last modified January 28, 2013, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/24th_Pursuit_Group.

- Kentner’s Journal Bilibid Prison, Manila, P.I. from 12-8-41 to 2-5-45 by Pharmacist Mate, Robert W. Kentner, page 59, located on “PFC Norman Hicks Hinckley Jr,” https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/152331012/norman-hicks-hinckley, accessed 2 Feb 2019.

- “Vermont Death Records, 1909–2008,” database online, entry for Charlotte Moore Hinckley, Ancestry.com, accessed 19 Oct 2011.

- “Memorial Page for Rosemary (Hinckley) Bitcon, https://www.saylesfh.com/notices/Rosemary-Bitcon, accessed 23 March 2019.

Image credits and sources

- Portrait of Norman Hinckley. Detail from Averill High School, graduating class of 1938, courtesy David Bartlett.

- Image 1: Prescott Administration Building at Good Will-Hinckley built in 1916, ca. 1926, found online at https://www.mainememory.net/artifact/14357, accessed 16 May 2019.

- Image 2: “POWs on the Bataan Death March. (U.S. Air Force photo)” VIRIN: 090803-F-1234S-024.jpg. Found at: https://www.nationalmuseum.af.mil/Upcoming/Photos/igphoto/2000510465/, accessed 16 May 2019.

- Image 3: Drawing by Al McGrew, H Company, 60th CAC, who was captured on Corregidor, found at “Pasay Camp (Nichols Field),” Center for Research: Allied POWs under the Japanese, Roger Mansell, Palo Alto, California, http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/philippines/nichols_pasay/nichols_plot.html, accessed 2 February 2019.

- Image 4: Courtesy Al McGrew, found at “Pasay Camp (Nichols Field),”

http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/philippines/nichols_pasay/pasay_school_plot.html, accessed 2 February 2019. - Images 6-7: Taken by Gail Kelly, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/152331012/norman-hicks-hinckley, accessed 2 Feb 2019.

- Image 8: Found on website of Sayles Funeral Home, St. Johnsbury, Vt,

https://www.saylesfh.com/notices/Rosemary-Bitcon, accessed 23 March 2019. - Image 5 & 9: Kentner’s Journal Bilibid Prison, Manila, P.I. from 12-8-41 to 2-5-45 by Pharmacist Mate, Robert W. Kentner, page 59, located on “PFC Norman Hicks Hinckley Jr,” https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/152331012/norman-hicks-hinckley, accessed 2 Feb 2019.

Documents