In late September 1945, weeks after the US retook The Philippines at WW2’s end, a young Japanese man approached a group of American soldiers in the wilds of Luzon island.

The wounded, starving man came toward the Americans with arms raised. He knew they would think him an uncaptured Japanese soldier — the enemy. And they did.

But this Japanese man claimed to be an American serviceman. And not just any serviceman. He identified himself as an American spy who was captured by and then escaped from the Japanese military.

The soldiers were hesitant. Could this Japanese man, wearing a Japanese uniform, really be American military? Or was he the enemy?

It was a question that many would ask for decades to come.

The only possibility

The man in question was indeed a Japanese-American. But back then, he was more commonly referred to as a “Nisei.”

Literally translated, Nisei means second generation — ie, the American-born child of parents born in Japan. During WW2, “Nisei” was used to describe to Japanese-Americans serving in the US military.

On May 6, 1942, “Lieutenant General Jonathan Wainright sent out the surrender message [from Corregidor island to the occupying Japanese forces], which was translated into Japanese by a Neisi [sic]” (Salm, pg. 5). There was only one Nisei serving with the American forces in this place at that time.

And his name was Richard Motoso Sakakida.

Hawaiian sugar-field beginnings

Richard Motoso Sakakida was born in Maui, Hawaii, on November 19, 1920, to Isoji Sakakida and Kiku Tanaka. They were Japanese immigrants who had spent some 20 years working on sugar plantations near Pu’unēnē, Maui.

Isoji (Richard Sakakida’s father) had come to Hawaii from Hiroshima, Japan, in 1899 when he was 22. Like most Japanese immigrants of the time, Isoji was seeking work. Crop failures of the late 1800s pushed many southern Japanese to Hawaii’s promising sugar plantations.

Working sun up to sun down, with only a small lunch-time break, plantation workers received minimal pay. They endured harsh treatment, poor nutrition, crowed, dilapidated barracks.

Isoji married Kiku Tanaka, also from Hiroshima, around 1905. The couple had six children, including one who died in childhood. Richard was their youngest.

The family relocated to Honolulu, Oahu, in the mid-1920s when Richard was a child. He went in to the public school system and in high school joined the ROTC (Reserve Officers’ Training Corps). Richard’s father, Isoji, died when Richard was a teen.

As a US counter-intelligence agent

In March 1941, some 9 months before the Pearl Harbor attack, 20-year-old Richard Sakakida was contacted by his former ROTC instructor and soon recruited as a sergeant in the U.S. Army. His Japanese-language skills helped him become an early member of the Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC).

In other words, an American spy.

After receiving counter-intelligence training, Sakakida and fellow Nisei Arthur Komori were sent to Manila, Philippines. They assumed alternate identities, infiltrated Manila’s Japanese community, and passed along intelligence to the U.S. military.

When Japanese forces began attacking The Philippines after Pearl Harbor, Sakakida worked on the American front lines. He translated Japanese documents, dairies, and other papers and broadcast surrender messages to the Japanese forces.

Nisei like Sakakida were in a dangerous situation. They looked like the enemy to their own American servicemen. And they were considered traitors by the Japanese. Nisei were often assigned guards to protect against both friendly and enemy fire. Some Nisei in combat situations fought against friends or family from Japan.

A vital part of the American surrender

By early 1942, Japanese forces were occupying The Philippines. Sakakida and Komori were ordered to Australia for their own safety in case the Japanese military actually conquered. Sakakida, however, opted to remain in the Philippines and let a third Nisei leave instead. This man’s wife and children lived in Japan and could be subject to capture themselves.

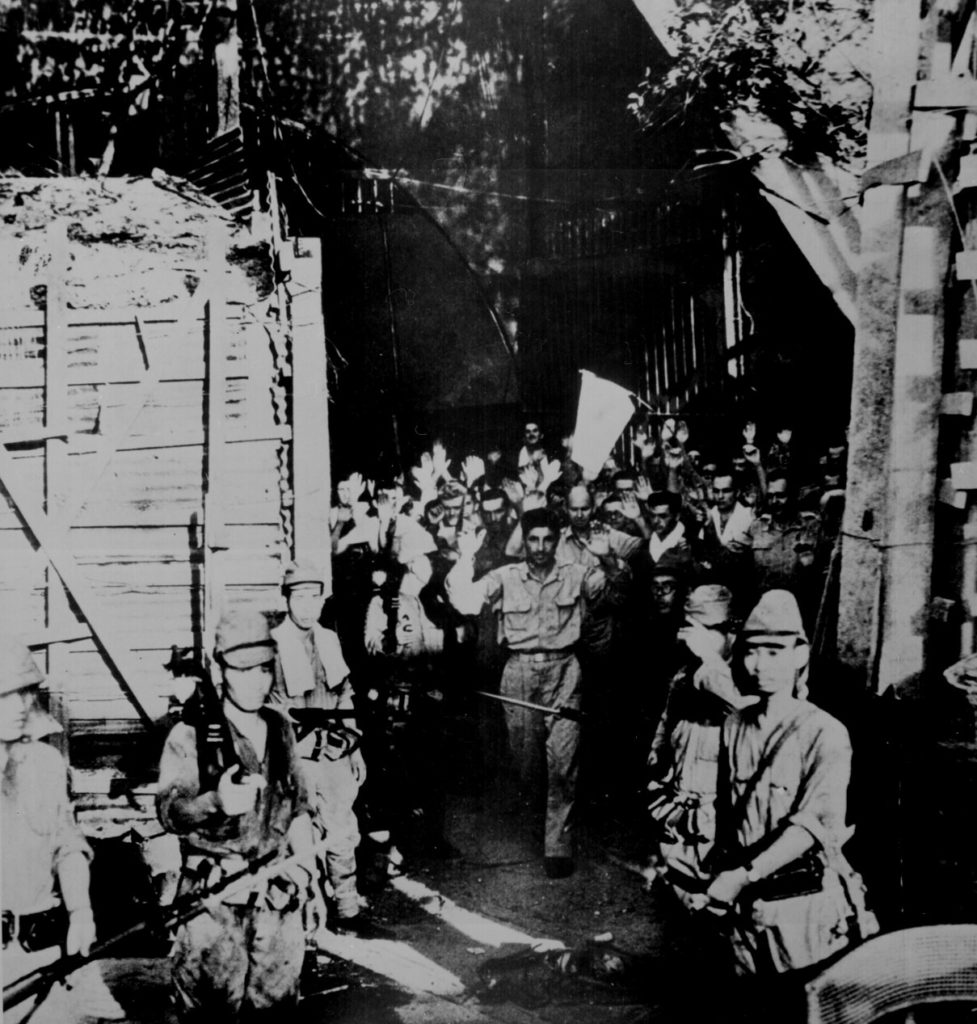

Thus, Richard Sakakida was the only Nisei with the surrendering American forces in Bataan and on Corregidor. And he played a vital role:

On 6 May 1942, I broadcast the surrender announcement in Japanese and that afternoon proceeded to Bataan from Corregidor with General Wainwright’s Chief of Staff for the surrender negotiation. Upon arrival we were lined up on the pier and individually questioned. I was asked if I was a Filipino. I answered “No, I’m an American.” Whamo! I was slapped on my face. My glasses flew and cut my face but my Japanese interrogator continued to slap me around. He was well aware that I was a Nisei.

–Richard M . Sakakida

This much we definitely know about Sakakida: He was a Nisei, a spy, a translator. But what happened once the Japanese captured him?

Well, this is where the story gets…interesting.

Sgt. Sakakida the American hero

There are two lines of thought about Sgt. Sakakida’s activities once captured by the Japanese. The mostly widely known story, goes like this:

Before the Americans surrendered, Sakakida’s counter-intelligence superior gave him this order: “We depend on you to get in on [the Japanese] side and try to get intelligence for the benefit of the U.S. Forces. I doubt whether you can do it because they will really work on you.”

The Japanese tortured and interrogated Sakakida for several months. As in strung up with his arms tied behind his back, beaten, and more. The Japanese believed him to be a U.S. Army spy. Sakakida claimed to be a civilian forced into translating for the Americans.

After months of fruitless torture, the Japanese decided Sakakida was telling the truth and eventually assigned him to work for a Japanese colonel. In this position, Sakakida gathered classified information, including some of Japan’s plans for invading Australia. He was able to pass along the info to guerillas in the Filipino resistance.

Late one night in August 1944, Sakakida and a group of Filipino guerillas, all disguised as Japanese officers, entered Bilibid Prison near Manila. They cut the lights, opened the gates, and enabled 500 Filipino guerillas, including a high-ranking resistance leader, to escape into the mountains. Sakakida, still working for the Japanese colonel, was at work the next morning to witness Japanese reaction to the breakout.

Sakakida continued to have access to classified Japanese information. And he continued to pass along that information to the resistance.

As the war turned against Japan, Sakakida came under increasing Japanese suspicion. He had passed along information that led to a number of successful American air attacks against the Japanese. It was time for Sakakida to escape.

Escape, injury, and jungle survival

Sakakida escaped from Japanese custody into the wilds of Luzon (the Philippine island that Manila is on). He described his jungle survival:

One day at dusk I was caught in a barrage of Japanese mortar shelling. I distinctly remembered three shells falling rather close by when I suddenly blanked out. When I came to I was unable to get up and my stomach area felt wet. I soon learned that instead of perspiration it was blood.

Remembering that there was a river close by I rolled and crawled until I finally made it to the river. I felt at least I would have water to drink and nurse myself. About three hours later the stench was so bad, I finally decided to check my stomach wound. Yes, it was infected and pussy. I carefully washed off the area and found a piece of shrapnel imbedded. Since I had no access to 911, I got my razor blade and became Doctor Sakakida.

Still unable to travel, I sat by the river. To my surprise I saw little crabs about an inch to inch and one half in the river. Every day I was able to catch 3 to 4 of them and enjoy them for dinner.

Finally I was able to walk, so started on my way. I decided to follow the river down stream hoping that it would take me out to civilization. It was very slow travel. I could only take a few steps and rest.

–Richard M . Sakakida

Sakakida survivied a reported 4 months on fruit, crabs, and other things he scavenged from the jungle. He was wounded and sick with dysentery, malaria, and beriberi.

It was in this bedraggled condition that he approached the group of American soldiers in September 1945.

Sgt. Sakakida the war-time traitor

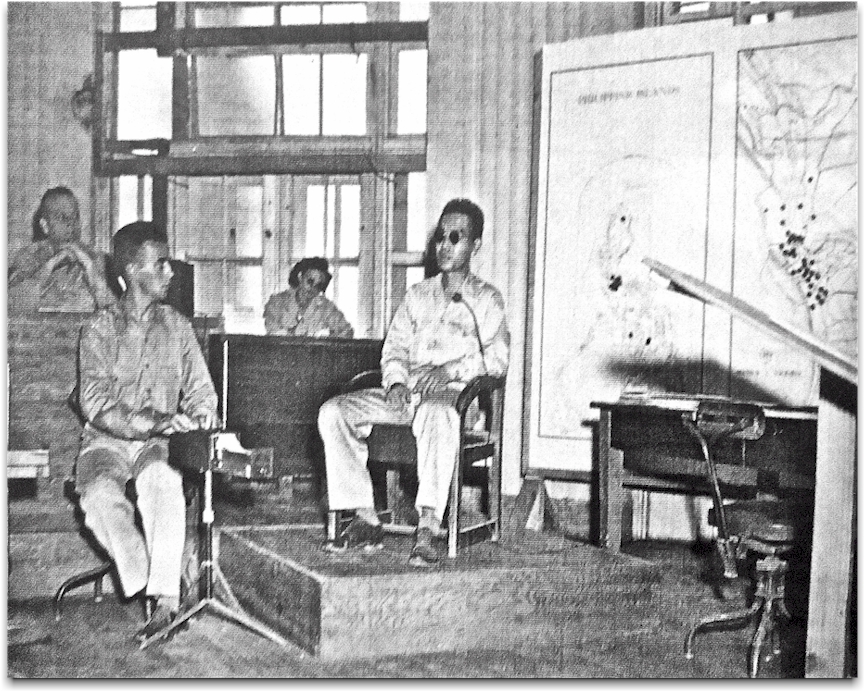

After revealing himself to those skeptical American soldiers, Sakakida was taken to American headquarters on Luzon. Once his identity as an American serviceman had been established, he was reunited with his CIC unit.

Here’s where it starts to get dicey: Some sources say he was interrogated extensively — as an enemy — by Army intelligence.

Then, in the 1980s and ’90s, stories regarding Sakakida’s war-time activities surfaced that have led some to believe he willingly sided with the Japanese once he was captured.

A Col. Carl Englehardt stated in 1989 that “A day or two [after the Americans surrendered on Corregidor], I ran into Staff Sergeant Sakakida near the West Entrance to Malinta Tunnel. Sure enough, he was wearing a Japanese uniform. He hurriedly told me that he had been impressed into the Japanese army because he was obviously of Japanes [sic] descent.”

Eye witnesses in Manila during the war have stated they saw Sakakida in Japanese uniform acting as an interpreter in court rooms. And documents show he was present for the trial and execution of an American woman accused of working with the Filipino guerillas.

In addition, researchers claim to have not found any mention of Sakakida in records or eye-witness accounts about the mass prisoner escape from Bilibid Prison. Researchers also claim that neither the US nor Filipino guerillas have any official record of Sakakida passing along information from the Japanese.

War crimes investigator and career Air Force man

Directly after the war, Richard Sakakida became part of the War Crimes Investigation team in The Philippines. He helped identify Japanese war criminals. In 1947 he transferred to the Air Force, where he worked in counter intelligence. He was stationed in Tokyo for nearly 20 years. Lieutenant Colonel Richard Sakakida retired in 1975.

He married Cherry M. Kiyosaki, also from Maui, in 1948. After retiring from the Air Force, Richard and Cherry lived in Fremont, California, until his death on January 23, 1996. They did not have children.

War-time hero or opportunistic traitor?

The main claims against Sakakida say that the widely spread story about his war-time activities comes from one place — Sakakida himself. Multiple WW2 documents, his critics say, show him acting in full cooperation with the Japanese during the war.

But…if he was instructed to “get in on [the Japanese] side and try to get intelligence for the benefit of the U.S. Forces,” then it’s not surprising to have documents and eye-witnesses stating his was “working for the Japanese” during the war.

On the other hand, “working for the Japanese” and “passing along Japanese intelligence” are two different things. He could have worked for the colonel and never passed along info, as critics claim.

Still, Sakakida received a Bronze Star for his WW2 activities. And in 1996, a US Senator told the entire Senate that Sakakida carried out “daring intelligence missions for his country.” This senator continued: “[Sakakida’s] sacrifices not only resulted in the advancement of the Allied cause during the Second World War, they reflected a great sense of duty and personal courage rarely seen even in that great conflict.”

What do you think?

So, what do you think? Was Sakakida a war-time hero or did he betray his country? Was he working for the Japanese on orders to infiltrate and confiscate. Or was he taking advantage of his nationality to avoid harsher treatment?

Write a comment below and let me know what you think.

Also, I’ve only overviewed Sakakida’s story here. If you want to know more about the accolades for and criticisms against him, you could check out these articles:

- “Undercover Agent in Manila” by Richard Sakakida

- “America’s Secret Army: The Untold Story of the Counter Intelligence Corps” by Ian Sayer and Douglas Botting

- “American Hero or Turncoat?” by Louis Jurika

- “How about Plain Old Traitor?” by Peter Parsons

Read next

Share Sgt. Sakakida’s story

Know anyone who would be intrigued by Sgt. Richard Sakakida’s story? Please consider sharing this post on social media or with anyone who would appreciate it. Thank you.

Sources

- “Nisei,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nisei, accessed 10 February 2019.

- “10 Overlooked Stories of Japanese-American Heroism in World War II,” Listverse, https://listverse.com/2015/09/19/10-overlooked-stories-of-japanese-american-heroism-in-world-war-ii/, accessed 10 February 2019.

- Ian Sayer and Douglas Botting, “America’s Secret Army: The Untold Story of the Counter Intelligence Corps,” Federation of American Scientists, https://fas.org/irp/congress/1996_cr/s960130a.htm, accessed 10 February 2019.

- “Japanese Laborers Arrive,” HawaiiHistory.org, http://www.hawaiihistory.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=ig.page&PageID=299, accessed 24 March 2019.

- Kelli Y. Nakamura, “Richard Sakakida,” Densho Encyclopedia, http://encyclopedia.densho.org/Richard%20Sakakida/#cite_note-ftnt_ref3-4, accessed 24 March 2019.

- Kelli Y. Nakamura, “Plantations,” Densho Encyclopedia, http://encyclopedia.densho.org/Plantations/, accessed 24 March 2019.

- “Richard Sakakida,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Sakakida, accessed 24 March 2019.

- Richard M . Sakakida, “Undercover Agent in Manila,” Japanese American Veterans Association, http://www.javadc.org/sw.htm, accessed 25 March 2019.

- “Richard M. Sakakida,” Japanese American Veterans Association, http://www.javadc.org/sakakida.htm, accessed 25 March 2019.

- Louis Jurika, “American Hero or Turncoat?” found online at http://corregidor.org/crypto/intel_01/sakakida_01.htm, accessed 18 May 2019.

- Col. Carl Englehardt in The QUAN, official publication of The American Defenders of Bataan & Corregidor, 1989, quoted in Louis Jurika, “American Hero or Turncoat?”

- Peter Parsons, “How about Plain Old Traitor?” found online at http://corregidor.org/crypto/intel_02/sakakida_01.htm, accessed 18 May 2019.

- Louis Jurika, “A Philippine Odyssey,” found online at http://corregidor.org/crypto/intel_01/A%20Philippine%20Odyssey%20-%20Louis%20Jurika.pdf, accessed 18 May 2019.

Images

- Image 1: “Richard M. Sakakida,” Japanese American Veterans Association, http://www.javadc.org/sakakida.htm, accessed 25 March 2019.

- Image 2: Maui sugar cane plantation laborers. From the Alexander and Baldwin archives. Found at Honolulu Civil Beat, https://www.civilbeat.org/2016/01/say-goodbye-to-hawaiis-last-sugar-plantation/, accessed 24 March 2019.

- Image 3: Manila waterfront, ca 1940, taken by Harrison Forman, held by American Geographical Society Library, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries, online at https://collections.lib.uwm.edu/digital/collection/agsphoto/id/18932/rec/2, accessed 17 May 2019.

- Image 4: “Surrender of American troops at Corregidor, Philippine Islands, May 1942.” National Archives and Record Administration. 208-AA-80B-1. National Archives Identifier: 535553. Found at https://www.archives.gov/research/military/ww2/photos, accessed 17 May 2019.

- Image 5: Bilibid Prison, Manila, found at “An Interview with Commander George Edward Morris, Jr., Regarding His Experiences in World War II,” http://www.zianet.com/tmorris/tedandkayinwwii.html, accessed 17 May 2019.

- Image 6: Luzon island landscape, from Adobe Stock Photos.

- Image 7: Sakakida interrogation, appears in Louis Jurika, “American Hero or Turncoat?” found online at http://corregidor.org/crypto/intel_01/sakakida_01.htm, accessed 18 May 2019.