The small boat sailed silently through a dark Manila Bay.

Its passengers, evacuees of bombarded Corregidor island, waited anxiously for sign of their promised rescue.

Were the months of hunger and war behind them? Would their rescuers slip through the blockade of Japanese warships?

Finally, at 7:35 pm they saw it: A recognition signal from a surfaced submarine.

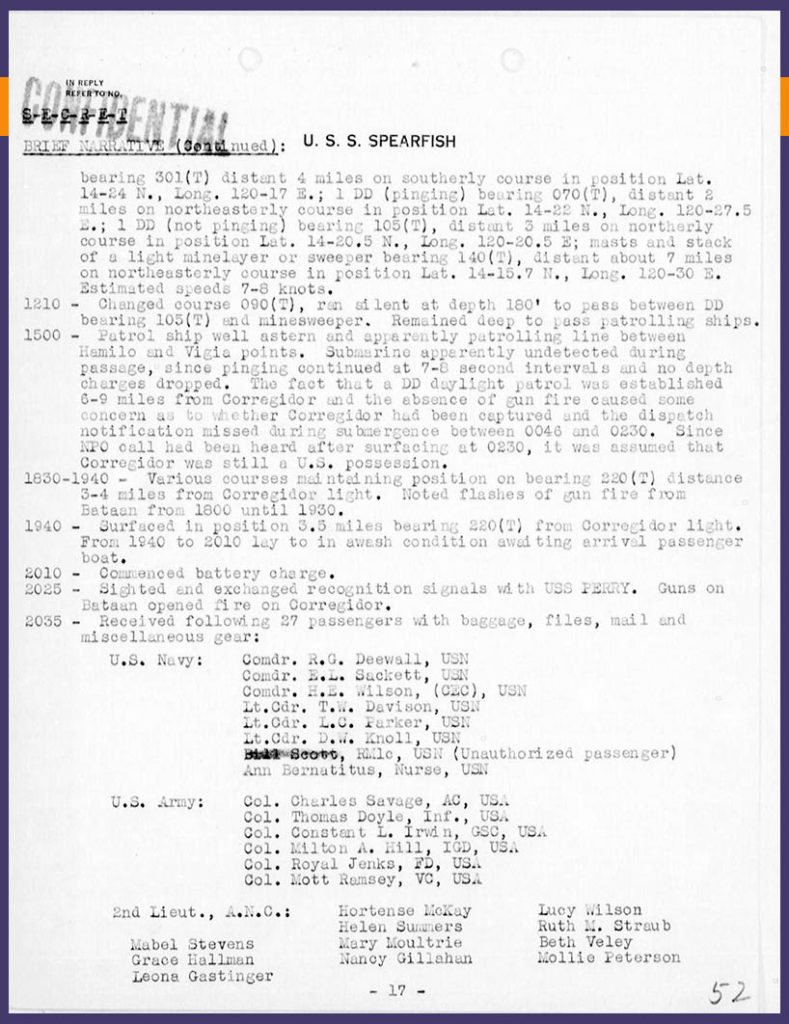

The small craft pulled along side the submarine, and 27 passengers climbed aboard the USS Spearfish with their baggage, important files, and mail.

“In final testimony of the hell left behind,” one of the passengers later remembered, “the dark bulk of Corregidor suddenly blazed with fires and bursting shells. . . . The Japs were starting to lay down a terrific, continuous barrage that was to mean the end of Corregidor.”

But the Spearfish, still undetected by the enemy, and those few American evacuees, including Commander Earl LeRoy Sackett, were safe — at least from the bombs pummeling Corregidor.

But could they evade the gauntlet of Japanese warships guarding the only route out of Manila Bay?

Submarine Commander Sackett

Commander Sackett was no stranger to submarines when he boarded the USS Spearfish.

He was a submarine-school graduate. And he’d served on 3 submarines, even commanding the third one.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Because, while Earl’s adult life was spent mainly at sea, his younger self couldn’t have been farther from the ocean.

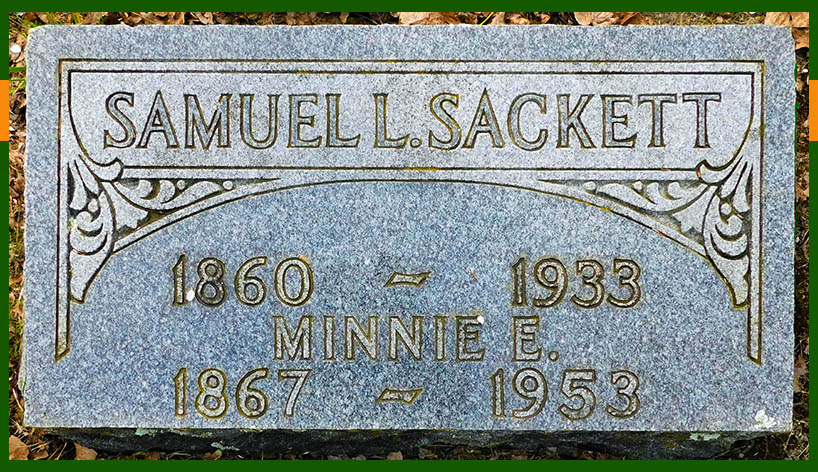

Born in Nebraska on March 29, 1897, Earl was the third of Samuel and Minnie Sackett’s 4 children. The family lived in Wisconsin, Idaho, and possibly Oregon by the time 18-year-old Earl joined the Navy in 1915.

By enlisting, Earl continued the military legacy of his Sackett family: His grandfather fought in the Civil War. And his great-great-great-grandfather served in the American Revolution.

Decorated Navy career

After a year in the Navy, Earl went to the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. He graduated as an Ensign and spent the early 1920s patrolling the ocean.

Despite his near-constant movement, Earl found time to marry Elizabeth Stanford. And in August 1922, their only child, Maidie was born in Norfolk, Virginia.

He went to sub school and served on 3 subs in the mid-’20s, then spent 2 years as a Naval Academy instructor. He received a masters’ in Mechanical Engineering in ’34 and spent the remainder of the ’30s moving up in rank while serving aboard various ships and at Navy bases.

Then, in February 1940, just a month shy of his 44th birthday, Commander Earl L. Sackett assumed command of the USS Canopus.

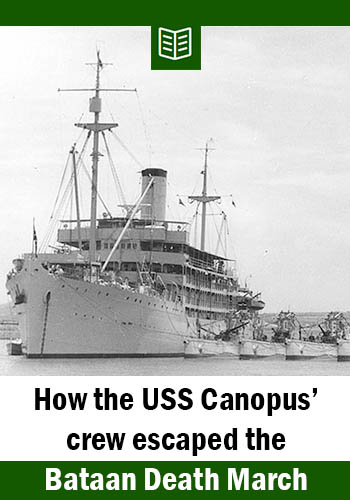

Taking command of the USS Canopus

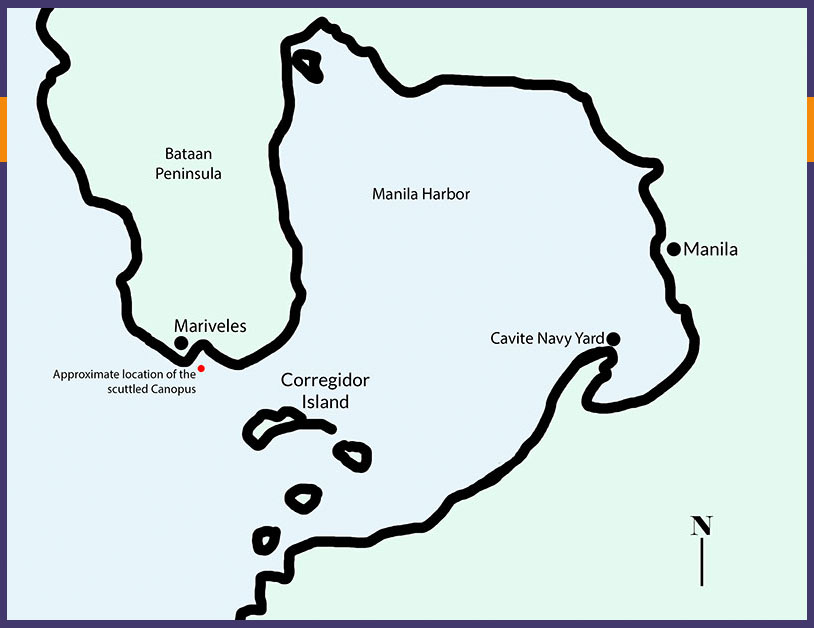

The USS Canopus was a submarine tender. It carried food, fuel, torpedoes, supplies, relief crews, and more for US submarines. She sailed mainly between The Philippines and China, attending to the US submarines that patrolled those waters.

On December 7, 1942, while Japanese planes were bombing Hawaii, the Canopus was in Manila Bay. The old ship had just finished a massive overhaul — getting more armor and better anti-aircraft guns.

Little did Captain Sackett know how immediately useful those additions would be.

Within hours, Japanese planes attacked military sites all around Manila. Under Sackett’s order, the crew painted the ship’s exposed parts the same color as the Manila dock and draped cargo nets to camouflage the ship.

But the Canopus wasn’t a high-priority Japanese target. Until, that is, she moved to Mariveles Harbor on Bataan Peninsula’s southern tip.

How to camouflage a warship in open water

On December 29, an armor piercing missile hit the Canopus. It shot through all decks and damaged the engine room, where escaping steam killed and wounded several of Sackett’s crew members.

A week later, Japanese planes attacked again. And Captain Sackett took drastic measures to ensure his ship and crew were no longer targets. In his own words:

It was useless to pretend any longer [that camouflage would hide the ship from enemy planes], but at least we could make them think that what was left was useless.

The next morning, when [a Japanese] scouting plane came over, his pictures showed what looked like an abandoned hulk, listed over on her side, with cargo booms askew, and large blackened areas around the bomb holes, from which wisps of smoke floated up for two or three days.

What he did not know was that the smoke came from oily rags in strategically placed smudge pots, and that every night the “abandoned hulk” hummed with activity, forging new weapons for the beleaguered forces of Bataan.

The ruse worked.

Japanese planes left the Canopus alone. For the next 3 months, Sackett and the Canopus crew supported the Americans defending Bataan. It was leadership that would earn Captain Sackett a Navy Cross.

But Bataan would fall. And in the early hours of April 9, 1942, Captain Sackett ordered the Canopus backed into deep water. He described: “There she was laid to her final rest by the hands of the sailors she had served so faithfully.”

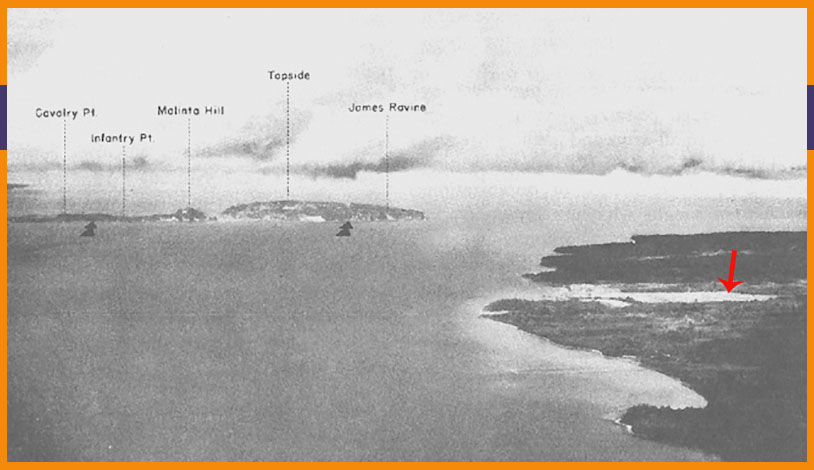

Sackett and the Canopus crew escaped to Corregidor island and joined the 4th Marines to defend the island fortress’s beaches.

Escaping Manila Bay on USS Spearfish

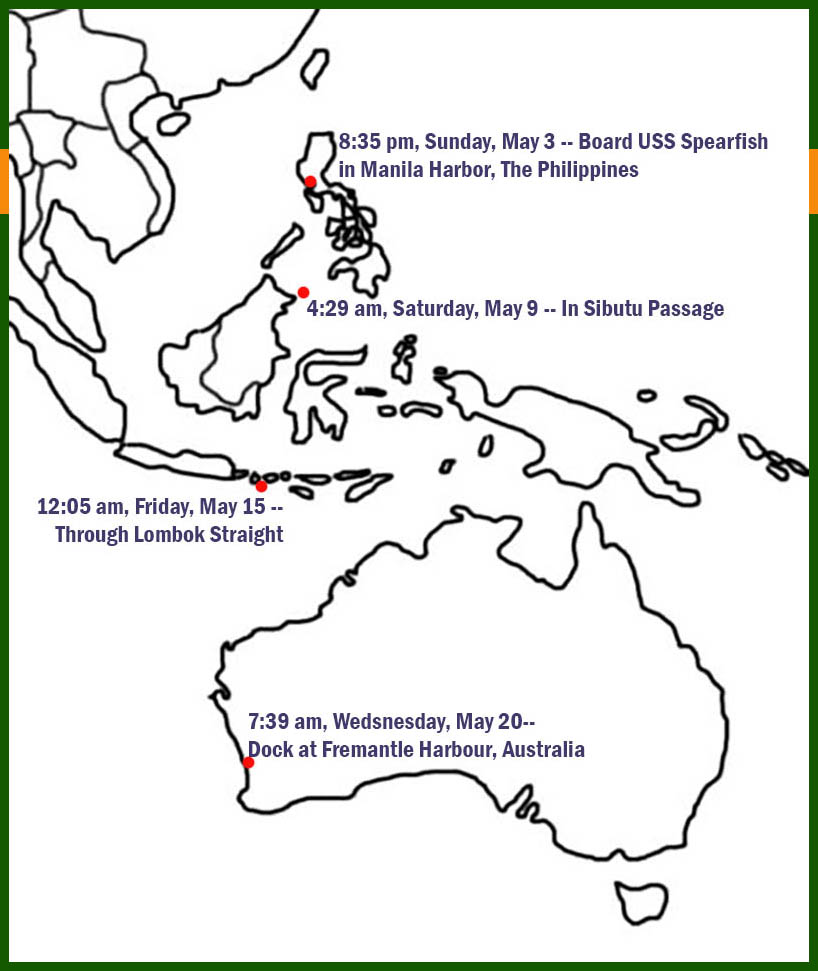

By 8:50 pm on May 3, 1942, less than a month after fleeing Bataan, Commander Sackett and the other Corregidor evacuees (including 2 stowaways, but that’s a story for another day) were on board the USS Spearfish.

Their journey to freedom was — well, it was delayed.

Manila Harbor crawled with Japanese ships. War ships. War ships that would attack — on sight — any American submarine.

So they waited as the active shelling and bombardment of Corregidor played out in front of them. At 9:52 pm fire erupted on Corregidor. The sub, still above water, moved farther away so that the fire’s light wouldn’t give away their position.

A half hour later, they spotted a Japanese destroyer. Immediately the submarine submerged. It silently moved at 5 knots (roughly 5.5 mph) through Manila waters, all the while listening for the destroyer they were trying to evade.

An anxious 24 hours under Manila Bay

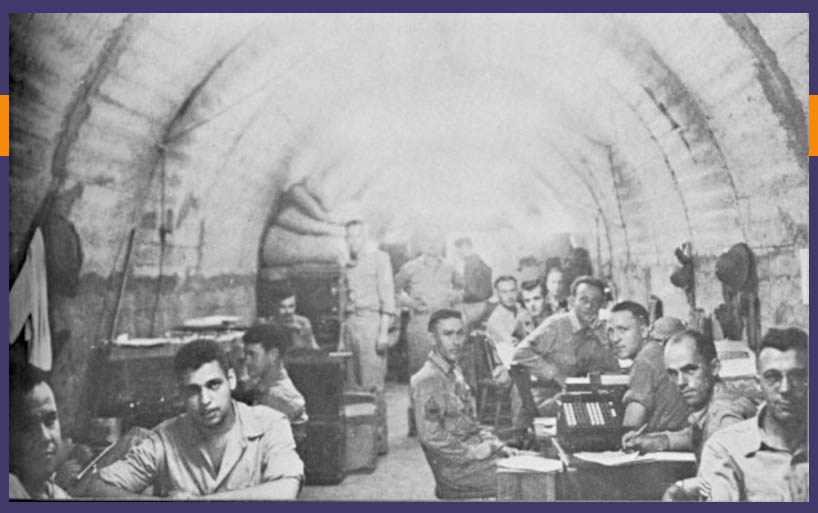

“Within the throbbing steel hull of the submarine,” Commander Sackett would later write, “sympathetic [submarine] crew members served up such food as the hungry refugees had not seen for months. Bunks were already at a premium, but the choicest ones were unselfishly given up to the passengers, with all hands put on a strict schedule for sleeping at different times during the day and night.”

Early the next morning, the sub — still submerged in Manila Bay — spotted two more Japanese destroyers. It dove deeper, changed course, and continued its silent, slow escape.

8:22 am. Yet another Japanese destroyer sighted. The sub again dove and changed course to evade.

At 7:10 that night, after 20 hours and 47 minutes under water, the Spearfish finally surfaced.

It had escaped Manila Bay with its various precious cargo. It was the last American submarine to do so.

Corregidor fell to the Japanese just 2 days later. Earl Sackett wrote:

When news of the fall of Corregidor came through the radio. . . faces were grim and grief stricken. We had hoped that there might be time for more submarines to be sent in, and more of our shipmates rescued. Now that last hope for our friends were gone. They had joined the “Missing in Action” roll call.

Journeying thru Japanese infested waters

Despite safely fleeing Manila Bay, the USS Spearfish was in enemy waters.

“Danger was by no means past. The gauntlet of Japanese-patrolled sea lanes still had to be run, and for weeks the only sight of the sun would be through a periscope. But the passengers had placed their destinies in competent hands, and they had no need to worry over such trifles.

— Commander Earl Sackett

The Japanese controlled all but a few small Philippine islands. And their ships patrolled the waters in and around The Philippines and surrounding nations.

For the next few days, the submarine continued it’s slow progress past the southern Philippine islands, remaining submerged during the day.

At 12:43 am on May 6, the submarine spotted two Japanese destroyers, which almost immediately altered course and sailed straight for the Spearfish. The submarine dove underwater, not resurfacing until 7:13 that night.

But the anxiety wasn’t over.

Not even an hour later, the lookout spotted a submarine — only 600 yards away! Fearing they’d been spotted by an enemy sub, the Spearfish immediately dove.

Fear. Worry, Held breath. Until, that is, word came that it was a false alarm. Not a submarine, probably a cloud or a rock. All was clear.

The Spearfish‘s final push to freedom

8 days after leaving Corregidor, the Spearfish was finally able to transmit a message to Navy command. The passengers had escaped. All were safe.

The submarine increased speed slightly as it sailed farther south.

But it wasn’t until they’d passed through Lombok Straight (on day 12) that they could increase speed to 15.5 knots (about 15.5 mph). And for the next 5 days their cruise was event free.

Captain Sackett reached the safety of Australia’s Freemantle Harbor at 7:29 am on May 20 — 17 days after fleeing Corregidor.

A final trip to Washington

Commander Sackett spent the rest of WW2 commanding the Submarine Repair Facility in San Diego and then on Fleet Admiral Chester A. Nimitz’s staff in Hawaii.

An almost 50-year-old Rear Admiral Earl L. Sackett retired from active Navy duty in January 1947.

He spent his retirement years in San Diego, California, where he died on October 7, 1970. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery just outside of Washington, DC.

Secret docs that broke open the Spearfish story

The gem of this week’s story are Submarine War Patrol Records.

Don’t let the official-sounding name tune you out. These records are awesome!

They’re basically daily journals with timed entries of a submarine’s location, enemy interaction, weather, and more. They literally tell the story of a sub’s journey. I used the patrol records to figure out the details of Commander Sackett’s escape from Corregidor.

It was fairly common knowledge that the Spearfish was the last sub out before The Philippines fell. But I wanted to know about the journey — what Commander Sackett would have experienced in this daring escape.

And the Submarine War Patrol report gave me details that aren’t in other narratives about the Spearfish.

Plus, you get the thrill of reading a document clearly marked “Secret” and “Confidential.” Don’t worry, they’ve been declassified. But you can still feel kinda cool reading through formerly “secret” docs.

I found the Submarine War Patrol Records on Fold3, a military-focused subscription website owned by Ancestry.com.

If you’ve got a WW2 submariner in your tree, try looking for their vessel in the Submarine War Patrol Records. Then page through the records and see what interesting stories you can discover.

Let’s end with a strange twist

Earl L. Sackett was the last captain that Alma Salm (my great-grandfather) served under before capture by the Japanese.

Sackett’s parents — Samuel and Minnie Sackett — are buried in a cemetery near Portland, Oregon. My father (Alma’s grandson) lives literally just a few blocks down the street from that cemetery.

It’s a strange, small world. Especially considering that Earl Sackett was born in Nebraska and Alma Salm came from California.

But coincidences are one of the serendipitous things about family history. You truly never know what you’re going to find…

Read Next

Please Share

Help us honor Commander Sakett by sharing his story. You could tell your children the daring escape from Corregidor. Email this post to your friends or family. Or share on your favorite social media site. Thank you!

Sources

- Burial Detail for Earl L. Sackett, ANC Explorer, Arlington National Cemetery, online at https://ancexplorer.army.mil/publicwmv/#/arlington-national/search/results/1/CgdTYWNrZXR0EgRFYXJs/, accessed 3 September 2019.

- Delayed Birth Certificate for Maidie Sackett, “Virginia, Births, 1864–2014,” Virginia Department of Health, Richmond, Virginia, Virginia, Birth Records, 1912-2016, Delayed Birth Records, 1854-1911 [database on-line], Ancestry.com, online at https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=9277&h=523906&ssrc=pt&tid=163190546&pid=422121363676&usePUB=true, accessed 16 September 2019.

- Earl L. Sackett, State of California. California Death Index, 1940-1997. Sacramento, CA, USA: State of California Department of Health Services, Center for Health Statistics, California, Death Index, 1940-1997 [database on-line], Ancestry.com, online at https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=5180&h=6413797&ssrc=pt&tid=163190546&pid=422121363486&usePUB=true, accessed 17 August 2019.

- Earl LeRoy Sackett, chapter X, History of the Original USS Canopus, 1943, found online at http://as9.larryshomeport.com/html/chapter_i.html, accessed 18 August 2019.

- “Earl LeRoy Sackett,” Arlington National Cemetery Website, online at http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/earllero.htm, accessed 18 August 2019.

- Edward C. Whitman, “Submarines to Corregidor,” Undersea Warfare Magazine, found online at https://www.public.navy.mil/subfor/underseawarfaremagazine/Issues/Archives/issue_15/subs_corregidor.html, accessed 18 August 2019.

- “History,” Naval Submarine Base New London, Commander, Navy Installations Command, found online at https://www.cnic.navy.mil/regions/cnrma/installations/navsubbase_new_london/about/history.html, accessed 17 September 2019.

- Memorial for RADM Earl LeRoy “Peach” Sackett, Find-A-Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/49307273/earl-leroy-sackett, accessed 17 September 2019.

- Memorial for Samuel L. Sackett, Find-A-Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/105467012, accessed 17 September 2019.

- Nathaniel Sackett, Sons of the American Revolution Membership Applications, 1889-1970. Louisville, Kentucky: National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution. Microfilm, 508 rolls, U.S., Sons of the American Revolution Membership Applications, 1889-1970 [database on-line], Ancestry.com, online at https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=2204&h=526475&ssrc=pt&tid=163190546&pid=422125214502&usePUB=true, accessed 16 August 2019.

- “Rear Admiral Earl LeRoy Sackett,” The Sackett Family Association, online at https://sackettfamily.info/g135/p135240.htm, accessed 17 September 2019.

- Samuel L Sackett household, Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910 (NARA microfilm publication T624, 1,178 rolls), Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C., 1910 United States Federal Census [database on-line], Ancestry.com, found online at https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=7884&h=166205012&ssrc=pt&tid=163190546&pid=422121363486&usePUB=true, accessed 16 August 2019.

- Samuel L Sackett household, United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Twelfth Census of the United States, 1900. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1900. T623, 1854 rolls, 1900 United States Federal Census [database on-line], Ancestry.com, online at https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=7602&h=32658818&ssrc=pt&tid=163190546&pid=422121363486&usePUB=true, accessed 16 August 2019.

- Samuel L Sackett, Card Records of Headstones Provided for Deceased Union Civil War Veterans, ca. 1879-ca. 1903, National Archives Microfilm Publication M1845, 22 rolls, records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, Record Group 92,National Archives, Washington, D.C., Headstones Provided for Deceased Union Civil War Veterans, 1861-1904 [database on-line], Ancestry.com, online at https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=1195&h=98508&ssrc=pt&tid=163190546&pid=422125213080&usePUB=true, accessed 17 August 2019.

- U.S. School Yearbooks, 1900-1999, database online, Ancestry.com, original data from US Naval Academy yearbook, 1920, page 81, accessed 3 September 2019.

- USS Spearfish: Report of the Third Patrol, pages 17-22, “U.S. Submarine War Patrol Reports, 1941-1945,” Fold3, database online at https://www.fold3.com/title/494/wwii-submarine-patrol-reports, accessed 18 September 2019.

Images

- Image 1. Earl L Sackett Portrait. U.S. School Yearbooks, 1900-1999, database online, Ancestry.com, original data from US Naval Academy yearbook, 1920, page 81, accessed 3 September 2019.

- Image 2. R-2 Submarine. From collections of the Naval Historical Center, photograph # NH 41873, found online at http://www.navsource.org/archives/08/08079.htm, accessed 19 September 2019.

- Image 3. Portsmouth Navy Yard. “Aerial View of Navy Yard, Portsmouth, New Hampshire,” from series Photographs Depicting Naval Shore Establishments, 1939 – 1947; Records of Naval Districts and Shore Establishments, Record Group 181; National Archives at Boston, found online at https://www.archives.gov/boston/finding-aids/navy-records.html#portsmouth, accessed 19 September 2019.

- Image 4. USS Canopus with submarines. Official US Navy image, image number 80-G-1014615, in the collections of the US National Archives and Records Administration, found online at Naval History and Heritage Command, Department of the Navy, https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/OnlineLibrary/photos/sh-usn/usnsh-c/as9.htm, accessed 19 August 2019.

- Image 5. Map of Manila Harbor. Created by Anastasia Harman.

- Image 6. Mariveles Harbor. From Louis Morton, “Japanese Plans and American Defenses,” The War in the Pacific: The Fall of the Philippines (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1953, found online at https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/5-2/5-2_29.htm, accessed 19 August 2019.

- Image 7. Interior of USS Bowfin. Found on TripAdvisor at https://www.tripadvisor.com/LocationPhotoDirectLink-g60982-d104386-i55628219-USS_Arizona_Memorial-Honolulu_Oahu_Hawaii.html, accessed 20 September 2019.

- Image 8. US troops in Malinta tunnel. US Army photograph, public domain, Photo ID: 3587779, VIRIN: 410000-G-GO214-1005, found online at https://www.dvidshub.net/image/3587779/troops-malinta-tunnel, accessed 19 May 2019.

- Image 9. USS Spearfish. “The Spearfish (SS-190) off Mare Island Navy Yard on 30 September 1944,” USN photo #5965-44, courtesy of Darryl L. Baker, found online at http://www.navsource.org/archives/08/08190.htm, accessed 19 September 2019.

- Image 10. Spearfish Escape Map. Created by Anastasia Harman.

- Image 11. Grave at Arlington. Burial Detail for Earl L. Sackett, ANC Explorer, Arlington National Cemetery, online at https://ancexplorer.army.mil/publicwmv/#/arlington-national/search/results/1/CgdTYWNrZXR0EgRFYXJs/, accessed 3 September 2019.

- Image 12. Spearfish patrol reports. USS Spearfish: Report of the Third Patrol, pages 17 and 22, “U.S. Submarine War Patrol Reports, 1941-1945,” Fold3, database online at https://www.fold3.com/title/494/wwii-submarine-patrol-reports, accessed 18 September 2019.

- Image 13. Headstone for Samuel and Minnie Sackett. Memorial page for Samuel L. Sackett, Find-A-Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/105467012, accessed 19 September 2019.