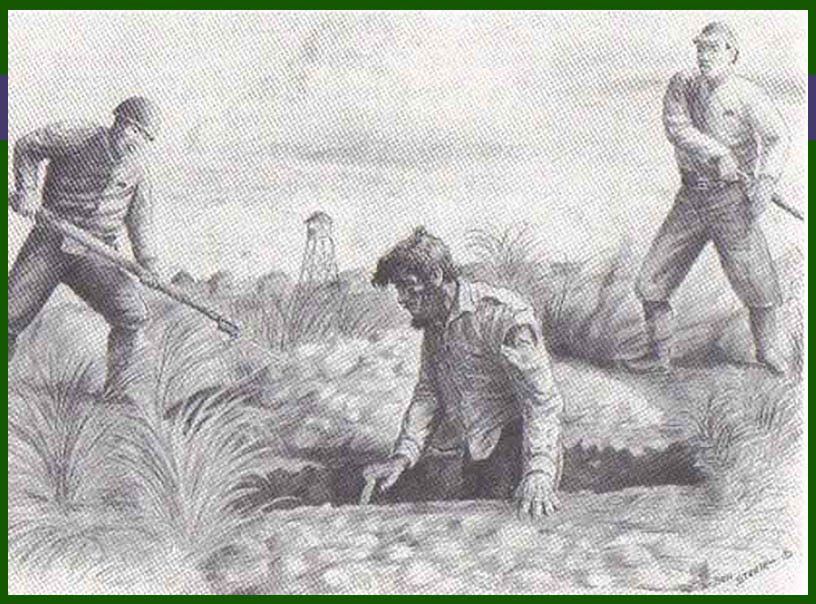

Japanese soldiers forced American POW John Burk to dig his own grave.

It was not an uncommon practice during WW2 in The Philippines.

Burk had been court martialed in summer 1943 after spending 3 torturous months in a Philippine dungeon. And he was sentenced to death.

Stop for a moment and just consider, if you even can, what it must be like — emotionally, mentally, physically — to dig the grave you’re about to enter. It’s difficult for me to begin to fathom such a horrifying experience.

But providence stepped in for Storekeeper Burk.

He never would occupy that grave. Instead, a happenstance event some 4 years prior saved his life — and likely those of 3 shipmates.

Sprinting into the Navy

John Burk entered this world on October 15, 1911, in Sparks, Nevada. But San Jose, California, was his real home, where he was raised among his DiFiore family, who were orchard-planting Italian immigrants.

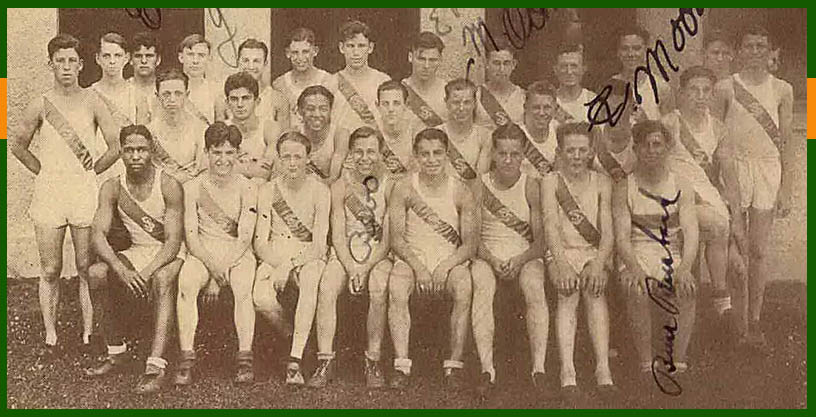

But fruit orchards wouldn’t be his calling. No, young John was a sprinter.

A sprinting “sensation,” in fact, at San Jose High School, where he graduated in 1929. Here’s a picture of his track team from his junior year (1928), when he was “one of the fastest sprinters in the” league:

John kept sprinting when he joined the Navy right out of high school. He was stationed at the naval air base in Hawaii in the early 1930s, where he was an All-Navy sprinter and eventually coached the track team. In 1932, he joined the Navy Olympic boxing team training at Annapolis, Md.

Diplomatic mission to Japan

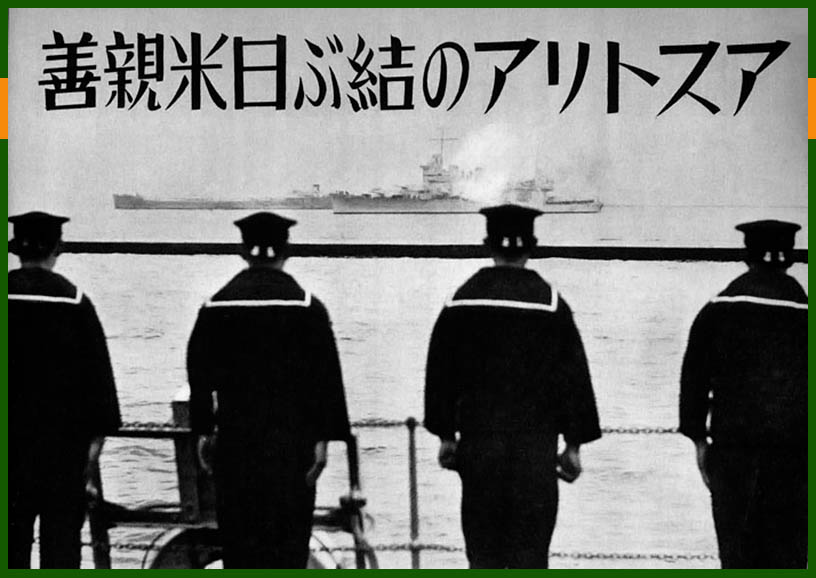

By the late 1930s, Storekeeper 2nd Class Burk had traded in his running shoes for sea legs. In 1939, he was assigned to the USS Astoria when the ship received a special mission: return the cremated remains of Hiroshi Saito, Japanese Ambassador to the United States, to Japan.

Burk and the Astoria left Annapolis, Maryland, on March 18, 1939. They sailed through the Caribbean and Panama Canal, then to Hawaii, and finally across the Pacific to Japan.

The Astoria, flying the Japanese flag and accompanied by 3 Japanese destroyers, sailed into Yokohama harbor on April 17, 1939. She honored Ambassador Saito with a 21-gun salute, then American sailors carried his urn ashore.

The Japanese were exceptionally grateful to the Astoria crew, who spent a week in Yokohama attending Ambassador Saito’s funeral and several other social events.

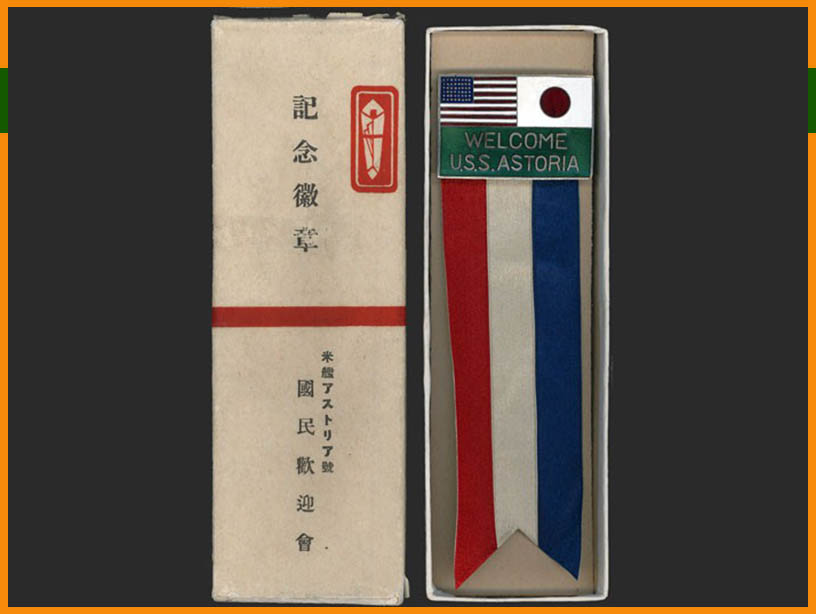

As a thank you for returning the ambassador’s remains, every crew member of the USS Astoria, Storekeeper Burk included, received a badge of honor.

Little did Burk know that the real honor of participating in this event was yet to come — and would save his life.

Front-row seat to WW2 in The Philippines

In October 1939, Burk joined the crew of the USS Canopus, a submarine tender who serviced American subs in China and The Philippines. And, on December 8, 1941 (mere hours after Pearl Harbor), Storekeeper Burk and the Canopus were in Manila harbor when the Japanese attacked.

Within weeks, American forces pulled out of Manila. Except John Burk and 3 other Canopus storekeepers — Arthur Lazcano, Gordon Fontaine, and William Patton — were left to blow up several warehouses filled with equipment and supplies the Navy didn’t want in Japanese hands. (For details on their mission, see Arthur Lazcano’s life sketch.)

The four men were successful, but by then Japanese military had invaded Manila. The uninjured, combat-ready Americans needed to figure out how to survive without being shot dead on site.

An American POW of the Japanese

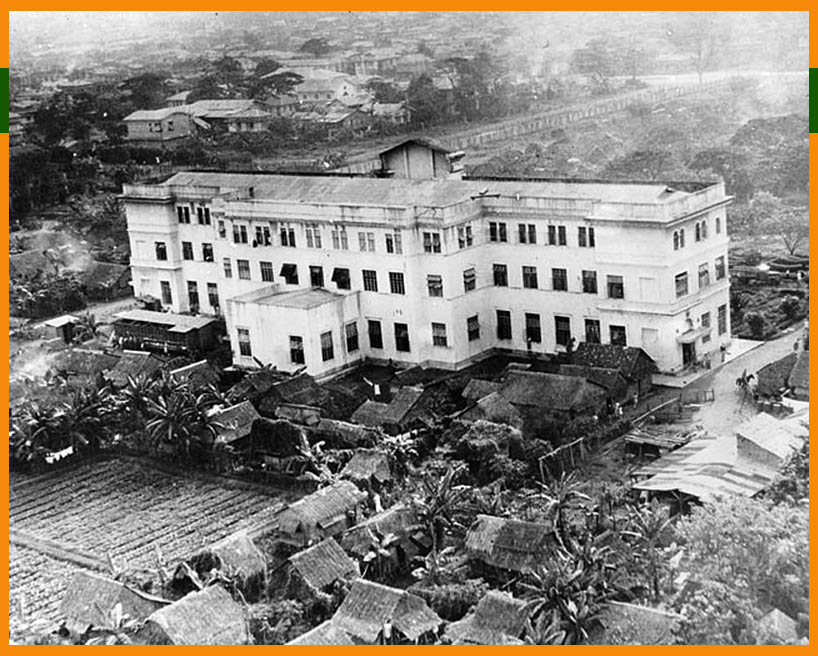

Burk’s obituary states that the 4 storekeepers “hid for several months in the mountains” near Manila. We know from other sources, however, that all 4 men pretended to be civilians and entered the Santo Tomas Internment Camp in Manila with other non-military enemies starting as soon as Manila fell in January 1942. So I’m not clear on how hiding in the mountains fits into the the story, although it sounds fascinating!

About a year later, roughly spring 1943, the Japanese discovered that military personnel were interred at Santo Tomas, so they gave an ultimatum — surrender now (to an unknown fate) or be executed immediately if discovered.

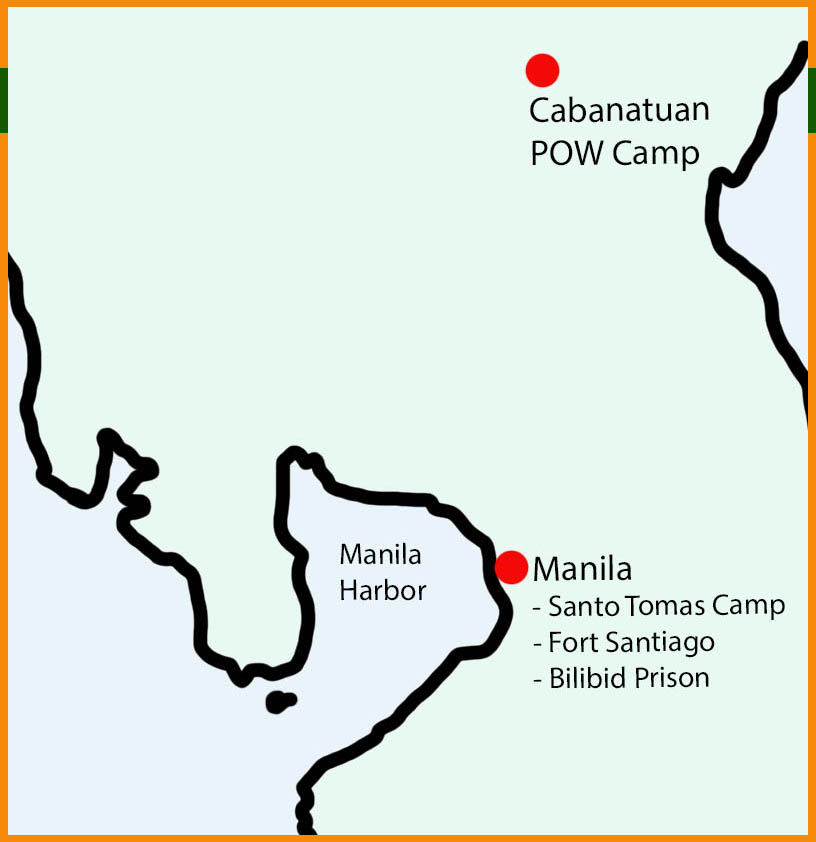

The 4 men surrendered and were immediately incarcerated in the dungeon of Manila’s medieval Fort Santiago.

”For three months we were beaten, starved, tortured and finally court-martialed,” John Burk later described.

And this is where Burk’s trip to Japan and his time in The Philippines all come together.

A providential blast from the past

At the court-martial’s end, apparently, John Burk was sentenced to death — and thus forced to dig his own grave.

But then, providentially, Seaman Burk’s past saved him. A Japanese general realized that Burk was part of the Astoria crew and that he had been decorated by Japan’s emperor in 1939.

That small ribbon-badge (pictured above) saved Burk from death. His sentence was changed to 50 years hard labor.

I’m not certain how Burk’s shipmates Lazacno, Fontaine, and Patton fit into the court-martial part of the story, however all 4 men were spared execution. (Perhaps the other 3 men’s association with Burk saved their lives as well?)

Regardless, “one day [in summer 1943] . . . into camp walked my storekeepers from the USS Canopus Burk, Fontaine, Lazcano, and Patton,” wrote Alma Salm, the Canopus‘s Chief Storekeeper who was already imprisoned at Cabanatuan POW camp about 70 miles north of Manila. Salm hadn’t seen his men for some 18 months, and likely thought them dead.

Waiting on the Yanks with tanks

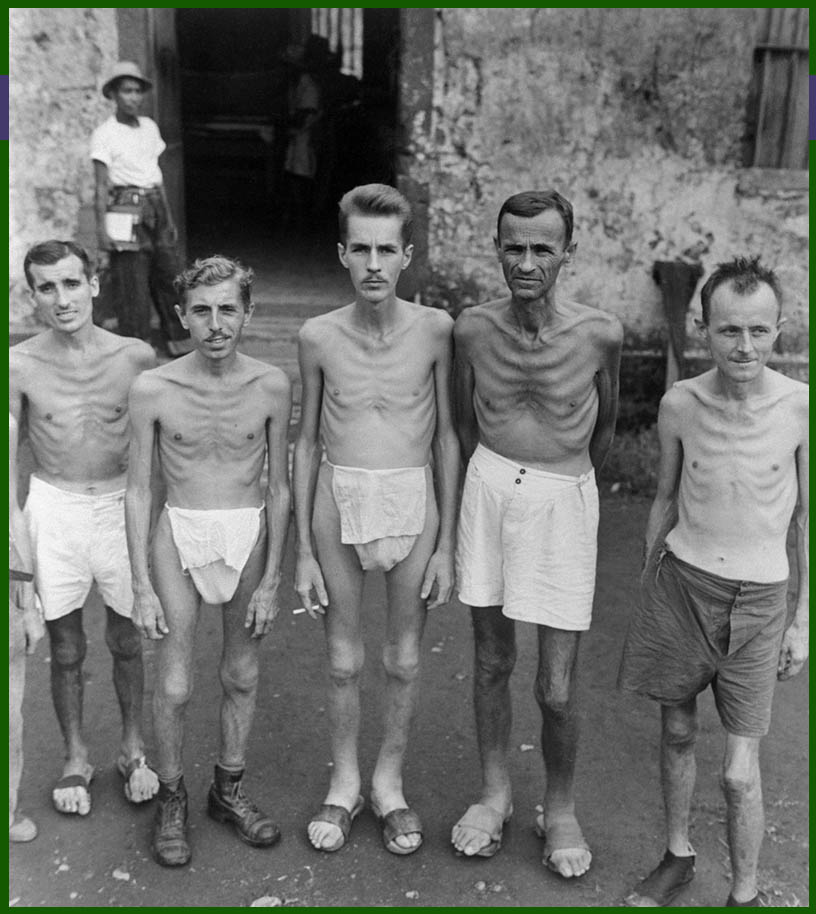

Life at Cabanatuan POW camp was not easy. The prisoners were starved, disease ridden, beaten, and worked like animals. Burk spent the next year and a half at various POW work camps in The Philippines.

On February 4, 1945, he was incarcerated at Bilibid Prison in Manila. There had been heavy fighting, mainly by air, for the past several days, and the hungry prisoners eagerly awaited the “Yanks with tanks with steaks and cakes.”

At 11:45 am, the Japanese guards left the prison because they “had been assigned another duty.” The POWs remained inside Bilibid for safety (since they were in the middle of a war zone) and even positioned their own guards to keep unwanted visitors out of the prison.

Around 6 pm on February 4, 1945, a rifle butt knocked a hole in one of the prison’s wooden shutters. Was it Filipinos? the prisoners wondered. Or Japanese?

As it turns out, both guesses were wrong.

American forces completely surrounded the prison walls, wanting to know what was inside. They had assumed Japanese forces, but were surprised to find 1,200 POWs — 700 military and 500 civilians, including women and children. The liberators passed cigarettes through the prison bars as they announced: “We’ve come to get you out!”

John Burk had been imprisoned for 37 months and weighed just 87 pounds.

”I am free, well, skinny and happy and hope to be with you soon,” the newly liberated Burk wrote to his kid sister, Miriam. “Any words I might use to express how terribly I missed you would be inadequate. We had it tough but it only made us realize how lucky we are to be Americans. Love to all, Johnnie.”

He also wanted some of his mother’s spaghetti and meatballs.

On February 18, 2945, Burk and other POWs from Bilibid Prison boarded the USS Pollux. 9 days later, he was transferred to the HMS Empire Mace. Storekeeper Burk was on his way home.

Thanks of a grateful nation

In 1946, so not long after his release, Burk received the “highest tribute of my naval career” — a letter from US President Harry S. Truman, which included these words:

”You have fought valiantly and have suffered greatly. As your Commander in Chief, I take pride in your past achievements and express the thanks of a grateful Nation for your services in combat and your steadfastness while a prisoner of war.”

President Harry S. Truman

John Burk remained in the Navy after liberation, eventually achieving Lt. Commander and receiving a Purple Heart. He retired in March 1958.

After the Navy, Burk settled in the San Francisco Bay Area, where he worked for a flight simulator manufacturer.

Ongoing family tragedy

While John Burk was imprisoned in The Philippines, his wife Emma was waiting for him in San Diego, California. She was a beautician, but I haven’t found much more about her.

I do know, however, that whatever happy reunion John and Emma had was short lived. Emma died sometime in the 1940s, and John Burk married Lois Kreutzberger, a single mom of 1 daughter, in 1950/51. John and Lois soon had 2 children of their own — a daughter and a son. They were married for 25 years, until her passing in February 1975.

Interestingly, John Burk’s obituary says he was married 3 times, and all 3 died before he did. Lois was his 3rd wife. Which suggests that John married and then lost a wife in the early-to-mid 1930s, before marrying Emma. Or that he married a woman in the late 1940s after Emma died, and that woman passed away before 1950/51 when he married Lois. Either way, 3 tragic losses for John.

Adding to that tragedy, John and Lois’s 10-year-old son, Richard, died in a car accident on December 11, 1963. John was driving. He never got over the loss.

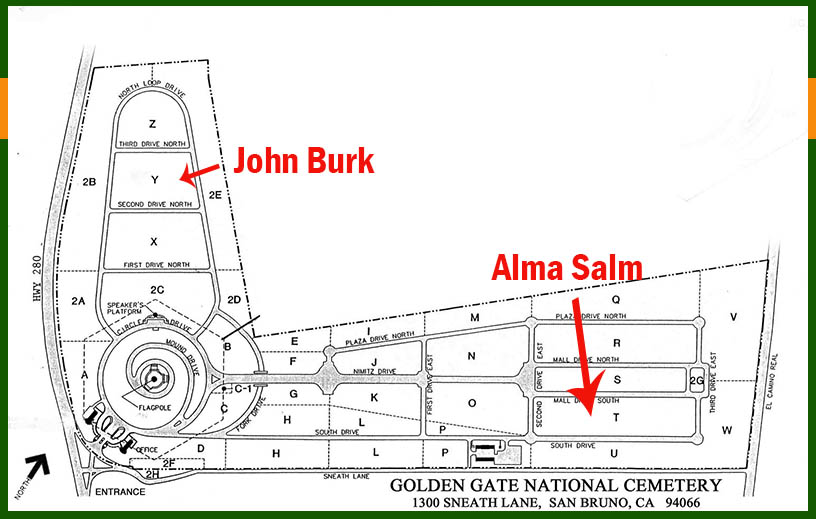

Reunited in death

90-year-old John Burk died of heart failure on August 10, 2002.

He’s buried with his son, Richard, in Golden Gate National Cemetery in San Bruno, California.

Interestingly, Burk’s resting place reunites him with another from his past. Chief Storekeeper from the USS Canopus, Alma Salm, who ordered Burk on the sabotage mission in Manila, is also buried in the same cemetery.

A strange little research helper

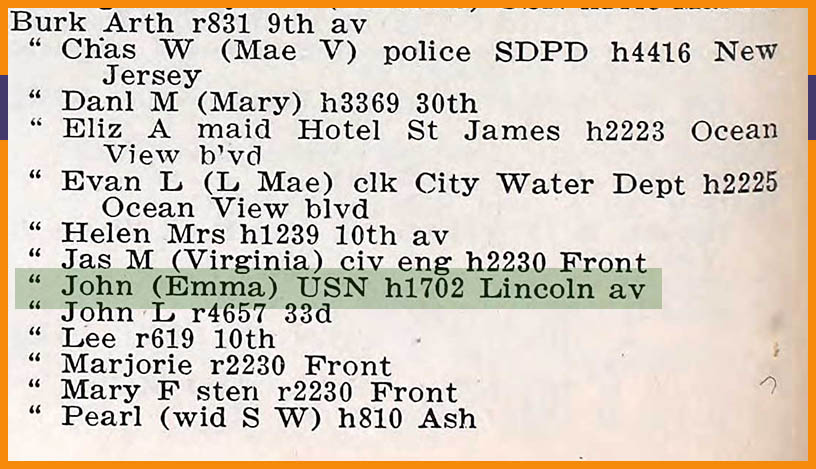

Tracking people in the 1930s, ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s can be difficult. Many birth marriage and death records — ie, some of the most valuable records for family history — are still private. And the 1930 and 1940 censuses, while awesome, give us only glimpses spaced 10 years apart.

So what to do when you’re stalking . . . uh, I mean, researching people in the mid-1900s?

I like to use City Directories.

City Directories are a precursor to phone books. Typically you’ll learn this info about someone:

- Individual’s name — often includes both husband and wife

- Occupation

- Address

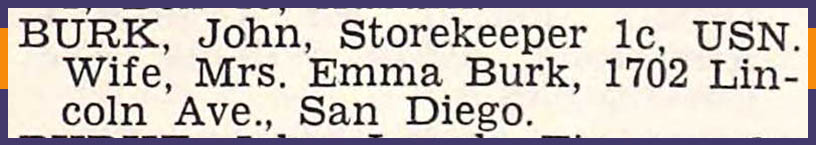

City Directories helped me learn about Emma Burk (John’s 1st or 2nd wife). I knew she existed because her name appears in a 1946 military record for him:

But I could not find anything else about her . . . except in San Diego City Directories. I know it is the right Emma Burk because she was living at the same address listed in the military record.

And while the City Directories didn’t tell me when Emma was born or when she died, finding her in several years of City Directories helped me narrow down a time frame of when she could have passed away.

See, John remarried in 1950/51, and his obit says that Emma “preceded him in death,” suggesting that she died while they were married. So Emma would have had to pass away before 1950/51. And between City Directories and military records, I know she was alive and married to John Burk between 1939 and 1945. So . . . that narrows down her death to between about 1946-50.

So next time you’re trying to track down a mid-20th century person, try out City Directories. I use the ones on Ancestry.com.

Read Next

Sources

- “Limited Track Team,” The Bell, page 106, 1928 yearbook for San Jose High School, San Jose, California, database: U.S., School Yearbooks, 1900-1999, Ancestry.com, found online at https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/1265/, accessed 6 December 2019.

- “The Saito Cruise 1939,” USS ASTORIA CA-34: The Official Home of “Nasty Asty,” http://www.ussastoria.org/The_Saito_Cruise_1939.html, accessed 10 December 2019.

- USS Astoria (CA-34), Wikipedia, found online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Astoria_(CA-34) , accessed 9 December 2019.

- “JOHN BURK, 90, PRISONER OF WAR SAVED FROM DEATH NAVY MAN HAD BEEN DECORATED BY JAPAN’S EMPEROR,” San Jose Mercury News, San Jose, California, August 17, 2002, found online at GenealogyBank.com, https://www.genealogybank.com/doc/obituaries/obit/105DA82385533F6C-105DA82385533F6C, accessed 9 December 2019.

- “List of Internees: Aalten, Hans Van to Dudley, Earl Carlyle, Sr.,” “Santo Tomas Internment Camp,” American Historical Collection, Rizal Library Special Collections Building, Ateneo de Manila University, Loyola Heights, Quezon City, Philippines, found online at http://rizal.lib.admu.edu.ph/ahc/gd_STIC.htm, accessed 7 December 2019.

- HMS Empire Mace, 27 Feb 1945, page 64, in database “U.S. World War II Navy Muster Rolls, 1938-1949,” Fold 3, online at www.fold3.com/image/309811459?rec=295459860&xid=1945, accessed 10 December 2019.

- USS Pollux, 18 Feb 1945, page 49, in database “U.S. World War II Navy Muster Rolls, 1938-1949,” Fold 3, online at www.fold3.com/image/309811413?rec=295459062&xid=1945, accessed 10 December 2019.

- “Bilibid Liberation Roster,” found online at https://www.west-point.org/family/japanese-pow/BLR.htm, accessed 10 December 2019.

- Sgt. Ike Thomas, “The Last Days of Bilibid,” found online at https://www.west-point.org/family/japanese-pow/Hudson%20Files/LastDaysBilibid.htm, accessed 10 December 2019.

- “New Bilibid Prison,” Wikipedia, found online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Bilibid_Prison, accessed 11 December 2019.

- Grave Locator, National Cemetery Administration, US Department of Veterans Affairs, found online at https://m.va.gov/gravelocator/index.cfm, accessed 11 December 2019.

- Burk, John entry in “Combat Naval Casualties, World War II, (AL-MO),” 1946, page 200, in U.S., Navy Casualties Books, 1776-1941, database online at Ancestry.com, accessed 7 December 2019.

- John and Emma Burk entry, San Diego, California, City Directory, 1939, page 88, in U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995, databases online, Ancestry.com, accessed 6 December 2019.

Images

- Image 1: “His Own” drawing. Ben Steele, “His Own — Camp O’Donnell,” Ben Steele’s Personal Chronically from Bataan to Hiroshima, found online at http://artmontana.com/article/steele/hisown.html, accessed 13 December 2019.

- Image 2. 1928 SJHS Track Team. “Limited Track Team,” The Bell, page 106, 1928 yearbook for San Jose High School, San Jose, California, database: U.S., School Yearbooks, 1900-1999, Ancestry.com, found online at https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/1265/, accessed 6 December 2019.

- Image 3-5: Astoria Crew in Yokohama. Photos from Brent Jones collection, found online at “The Saito Cruise 1939,” USS ASTORIA CA-34: The Official Home of “Nasty Asty,” http://www.ussastoria.org/The_Saito_Cruise_1939.html, accessed 10 December 2019.

- Image 6: USS Canopus. USS Canopus. Official US Navy image, image number 80-G-1014615, in the collections of the US National Archives and Records Administration, found online at Naval History and Heritage Command, Department of the Navy, https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/OnlineLibrary/photos/sh-usn/usnsh-c/as9.htm, accessed 19 August 2019.

- Image 7: Arthur Lazcano picture. “New Jap Torture Related by Liberees Here,” Oakland [California] Tribune, September 12, 1945, page 12, online at WorldVitalRecords.com, accessed 19 October 2011. Gordon Fontaine picture. “Rites Monday,” Green Bay Post-Gazette, Green Bay, Wisconsin, March 18, 1948, page 5, online at Newspapers.com, accessed 2 October 2019.

- Image 8: Santo Tomas Internment Camp. US Army photo, public domain, Wikimedia Commons, found online at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Santo_Tomas.jpg, accessed 2 October 2019.

- Image 9: Dungeon at Fort Santiago. Licensed from Adobe Stock Images.

- Image 10: Map created by Anastasia Harman.

- Image 11: Aerial view of Bilibid Prison. “Bilibid Prison, Manila, Philippines, Feb. 1945,” uploaded by John Tewell, Flickr, found online at https://www.flickr.com/photos/johntewell/6058065261, accessed 15 October 2019.

- Image 12: Liberated POWs at Bilibid. Bettmann/Corbis photo found online at http://projects.wsj.com/lobotomyfiles/?ch=sidebar, accessed 10 December 2019.

- Image 13: Graves of John and Richard Burk. Memorial for John Burk, Find a Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/73905655, accessed 11 December 2019. Memorial for Richard John Burk, Find A Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/73904467/richard-john-burk, accessed 11 December 2019.

- Image 14: Map of Golden Gate Cemetery.

- Image 15: Burk’s Military record. Burk, John entry in “Combat Naval Casualties, World War II, (AL-MO),” 1946, page 200, in U.S., Navy Casualties Books, 1776-1941, database online at Ancestry.com, accessed 7 December 2019.

- Image 16: 1939 City Directory. John and Emma Burk entry, San Diego, California, City Directory, 1939, page 88, in U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995, databases online, Ancestry.com, accessed 6 December 2019.