This is the 7th excerpt from Alma Salm’s POW memoir. It picks up where the sixth excerpt — 8 Horrific Things Japan Did to POWs in Manila — ends.

Thirty-six hours later, about three o’clock in the morning of May 26, 1942…

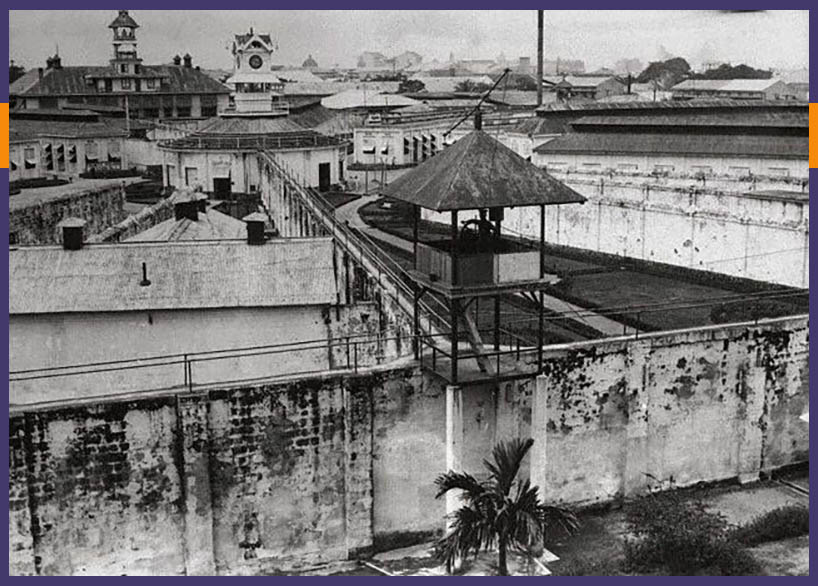

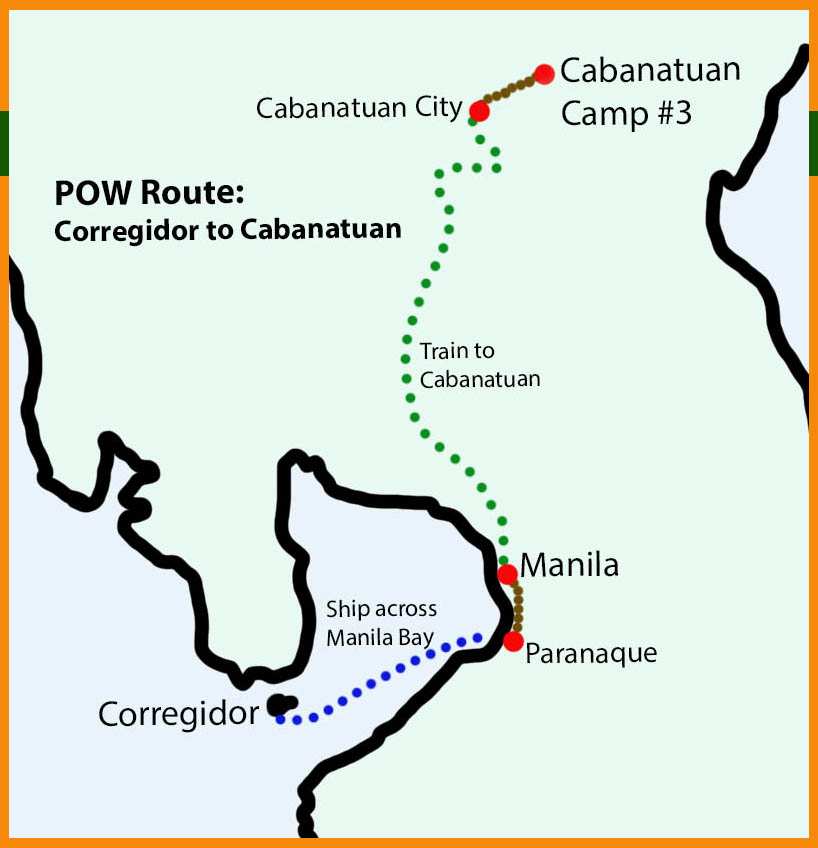

A contingent of about fifteen hundred officers and men of the various services were marched in one long column thru the [Bilibid] Prison gates down to the Manila Railroad station.

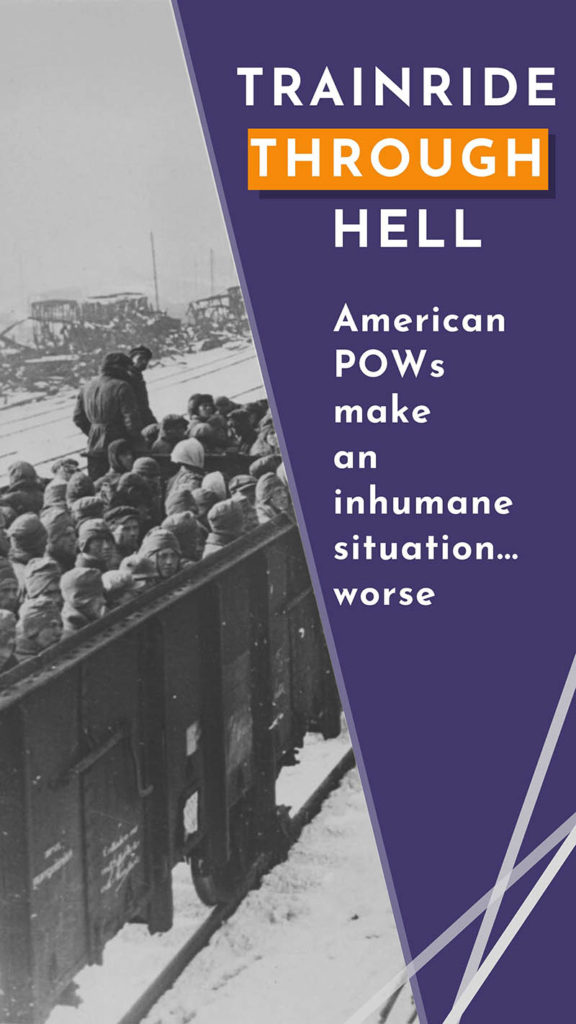

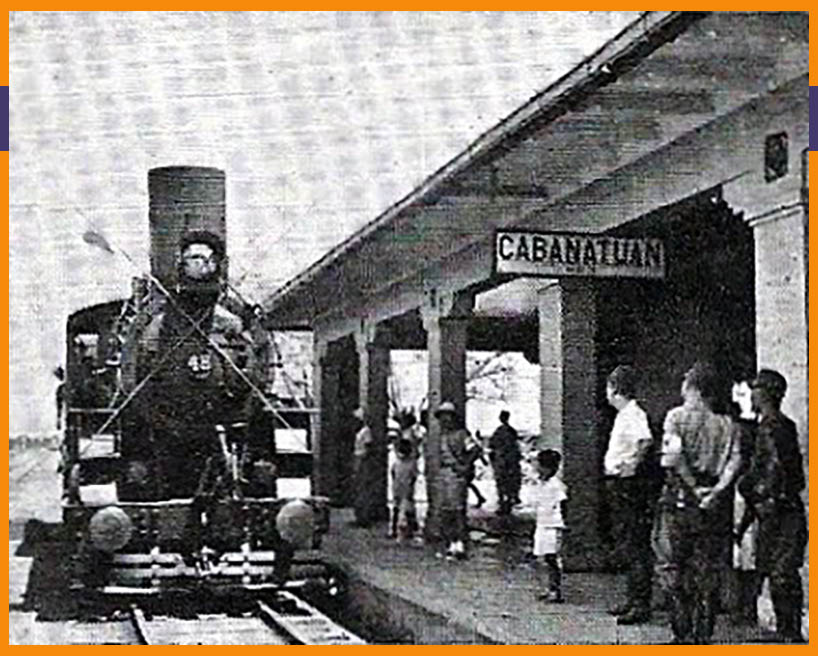

We were ordered into a train of box cars waiting for us.

These box cars were much smaller than the standard size used in the United States, but nevertheless they literally stuffed one hundred men and officers in each car until, figuratively speaking, a shoe horn had to be used to squeeze in the last man. No cattle car was ever so crowded.

Obviously there were no facilities or conveniences therein. We sat down or stood up the best we could in our filthy cramped quarters. There was very little ventilation, except that which came in through the small slide doors in the middle on either side of the car, at which point two Jap armed guards took their positions.

Inhumane conditions for the American POWs

The train pulled out about 6:30 am and rattled northward across the broiling Luzon plains with it’s destination the town of Cabanatuan about seventy-five miles away in the rice paddy country.

The conditions under which we traveled these eight hours in the cars is a story itself.

The hot, still tropical air and the searing sun burning down on the thin metal roofs of those cars plus partial ventilation almost stifled those who could not get near the side-door openings.

Many men defecated in the car because of the frequent urge in view of their active dysentery. The lack of oxygen had the effect of making many of us drowsy.

I was suddenly aroused from my lethargy by sharp words ahead of me.

And the insubordination begins

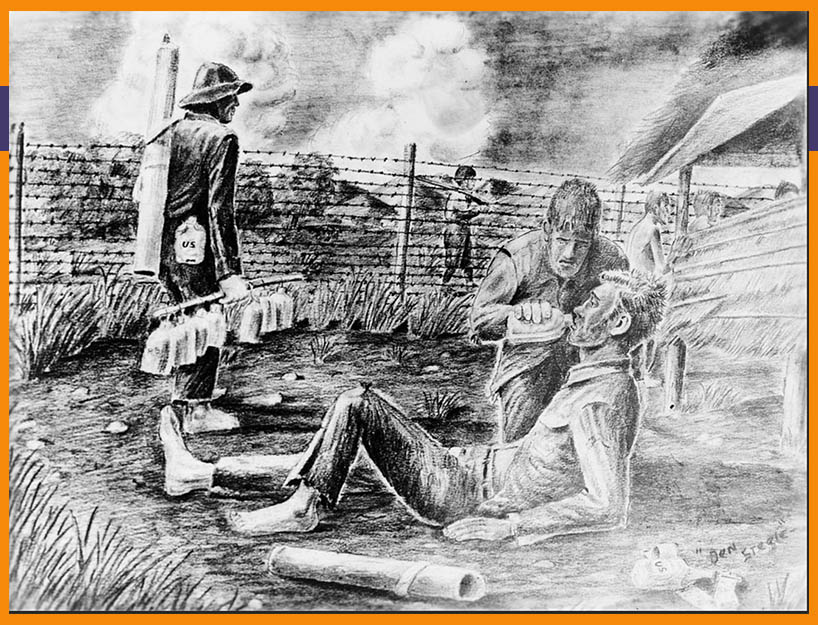

A large Army corporal in violent dispute with an Army captain was calling the officer some hard names. The latter, a very inoffensive individual, attempted to discipline him quietly, but this infuriated the “non-com” who answered with blows on the officer.

Other enlisted men entered into the argument.

One said, “You can get away with giving us orders in the Army but not now, brother. You are a prisoner of war just like the rest of us. You don’t have a damn bit more authority than we do. If you think so, try doing something we aren’t permitted to do and see if you can get away with it.”

Others joined in.

“Yeah! Try it.”

Some acted like regular hoodlums and seemed for the moment to have thrown away all respect for the officer’s rank and the authority it represented.

However, as ugly as some of these men were, it seemed they were to be more pitied than condemned (although I certainly do not condone, for an instant, the insubordination). They were weary, half sick, and irritated youngsters for the most part with combat fatigue due to the long months on the firing line. And now prisoners of war under the worst possible conditions was more than a lot of them could stomach at the moment.

“Go to hell” — being POWs puts everyone on the same level

During my internment in the prison camp, arguments between men and officers became common until no one paid much attention to them.

A private would tell an officer to “go to hell” when receiving — not an order — but instructions or a request. I fully believe, however, considering the number of men involved, this sort of thing was the exception rather than the rule although these minority ran into many hundreds. The majority of the trouble makers were new inductees, and their actions for the most part indicated lack of proper military indoctrination, training, and discipline. Most old regulars conducted themselves more understandingly toward the officers.

Officers seldom gave orders, merely giving instructions as a Group Leader of one hundred men in a labor battalion.

Japs always referred to the Group Leader (ie, officer in charge) as captain or Tai (meaning superior person). And the Tai was expected to have the men do as he was instructed by the Japanese. He also had the responsibility, and if the men didn’t do the job correctly, the Japs not only punished them but the Tai also.

However, in that [labor battalion of] hundred, there were dozens of officers carrying out the slave labor details along with the privates and the “non-coms.” The only respect shown was such as one man would accord another according to whether he liked him personally or not as man to man and not as an officer.

The inexorable leveler of being a fellow prisoner placed us more or less on one plane.

How POW camps bring out true human nature

Nevertheless, bitter feelings were felt and spoken continually as time of captivity lengthened.

But remember, the men were becoming disheartened as the months passed into years. They were half-sick with frayed nerves due to their continual hunger, facing uncertain existence and future. All they wanted was to somehow keep alive, to escape the dreaded infections, and to be able to have their liberty restored to them again after paying such a frightful price for it.

So, whatever they said or did, right or wrong as judged by our American concepts of morals, laws, conventions, and Christianity, remember that their inhuman existence visibly affected and changed their lives and philosophies.

The best and the worst in men came out. Some were weak, sordid, mercenary, and would exploit or steal from others. Stealing food was the worst crime; the cardinal sin a man could commit against his fellow-man in a Japanese prisoner of war camp. Others had superlative characters — held up — sacrificed to their own detriment to help those in greater need.

Those who exploited or stole without compunction from their fellow-men were a type who just didn’t care. They were already in a prison — one far worse than any in the United States could be — and threats of punishment or discipline after they were released didn’t phase them one iota.

Cabanatuan City: Gateway to the hellish camps

Upon arrival at the town of Cabanatuan, we stumbled off the train and were bivouacked for the night in a barb wire enclosed field about a mile from the railroad station.

I was very fortunate in being able to bribe the Jap guard in our new cage and had him motion a Filipino woman vendor to come over to the fence.

I bought a water pail full of luscious mangos and some small bananas. They didn’t last more than a few minutes, for I was instantly surrounded by my fellow prisoners who begged to buy the fruit their systems needed so badly.

We rigged up our pieces of shelter halves, blankets, or whatever covering one was fortunate to possess, as protection against the ever-present blistering Luzon sun and crawled underneath. The ground was our bed. For those who didn’t have coverings the sky was their roof.

It rained as usual that night, and we looked and felt like drowned rats.

At three o’clock the next morning, after being given a rice ball about the size of a baseball and a few spoonsful of very thin plain onion water that was cooked by our men under Japanese direction, we were formed into different columns of one hundred men each and marched out in relays halting in the main street of north Cabanatuan.

Here we counted and recounted by yelling, gesticulating Japanese guards.

Read Next

Images

- Image 1. Bilibid Prison. Chief L., on Pinterest, found online at https://www.pinterest.com/pin/341992165429002745/?nic=1, accessed 16 October 2019.

- Image 2. Map showing route to Cabanatuan. Created by Anastasia Harman.

- Image 3. Red Army POW transport. Found online at https://www.pinterest.com/pin/329255422728612202/?lp=true, accessed 16 October 2019.

- Image 4. Cabanatuan POWs. Found online at https://www.pinterest.com/pin/93660867222677847/?lp=true, accessed 16 October 2019. Note: I’ve had a difficult time finding an actual original source for this drawing. Writing in the lower right corner might be a name. But as of right now, I don’t know the original source.

- Image 5. Cabanatuan train station. Added by Dirk tow mater celoso, Philippinetrains Wiki, on Fandom, found online at https://philippinetrains.fandom.com/tl/wiki/Cabanatuan_Station, accessed 16 October 2019.

![Train Ride thru Hell: American POWs Make an Inhumane Situation…Worse [Memoir #7]](https://www.anastasiaharman.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Train-ride-thru-hell-featured-image-367x680.jpg)