A Japanese plane flew over The Philippine’s southern Bataan peninsula in January 1942 looking for targets.

To be specific, it wanted American ships that had survived the earlier bombing runs.

The pilot was encouraged — an abandoned American ship tilted in Mariveles’s small harbor. Bomb holes peppered her deck, and smoke rose from the hull.

The previous air attacks had succeeded. This American ship was no threat.

Except…

Well, there was something the Japanese scout didn’t realize. The problem was he’d trusted his eyes. And, really, who could blame him — that was his job, right? Scouting. Looking. Seeing.

But that’s where things go wrong, isn’t it? Because, you know, looks can be deceiving.

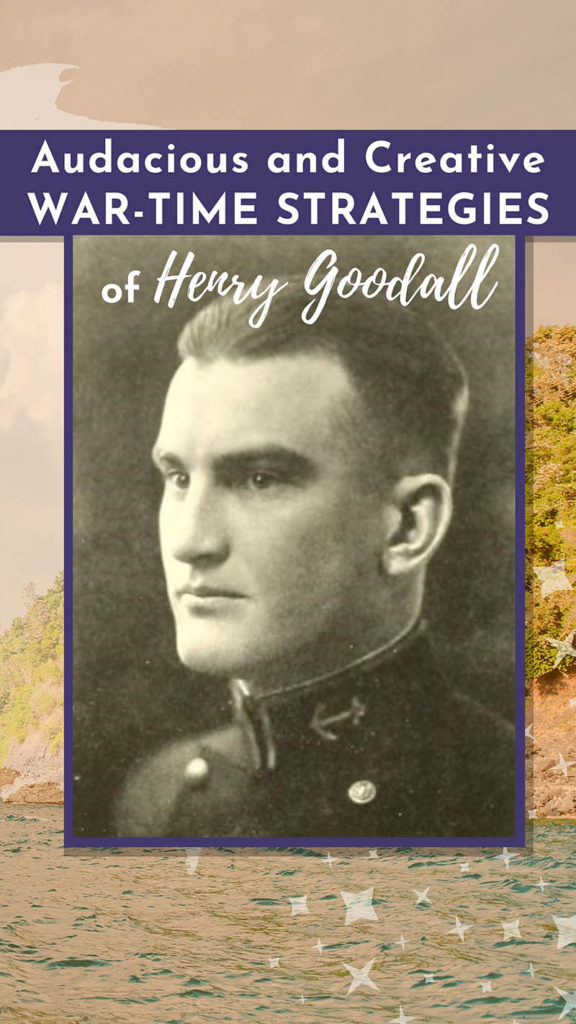

In fact, the decrepit-looking USS Canopus was a hoax. And, years later, the President of the United States would thank one specific man for this masterful hoax — Lt. Commander Henry Goodall.

That Midwestern hometown football star

Henry William Goodall grew up in Salina, Kansas, with his mother and much older siblings, who all worked to support the family after Henry’s father died when Henry was 7.

Born September 2, 1900, Henry became a handsome young man and star football player for his hometown high school, graduating in 1919.

After graduation he worked at a poultry house in Salina, then joined the Navy in September 1920 and spent the 1920s and ’30s working his way up the naval officer ranks. In 1929, he married Eugenia Strickland.

A ship in disguise?

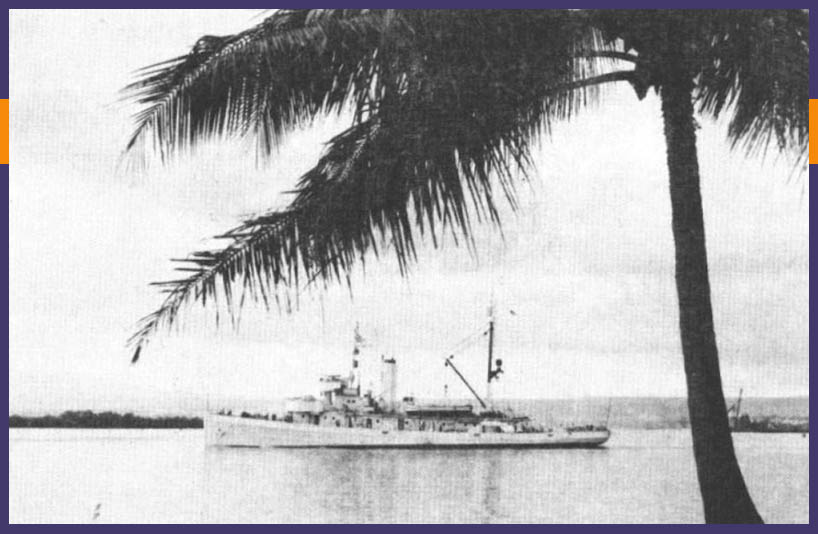

When Japanese aircraft attacked Manila, Philippines, on December 8, 1941, Lt. Commander Henry Goodall was the 41-year-old Executive Officer for the submarine tender USS Canopus. By order of Captain Earl Sackett, the crew repainted the Canopus to match Manila’s docks and hung fishing nets to disguise her as a fishing boat from Japanese bombers.

The camouflage worked, and the Canopus was among the handful of American ships able to retreat from Manila to Mariveles Harbor on December 26, 1941. But now the camouflage would no longer hide the ship, since the Japanese knew every ship in Mariveles Harbor was American military.

Thus the Canopus became a target.

And targeted she was. On December 29, an armor piercing missile hit the Canopus. It shot through all decks and damaged the engine room. A week later, the Japanese attacked again.

Abandoning the USS Canopus

Lt. Commander Goodall and Captain Sackett still had some hands to play, however.

They couldn’t pretend Canopus was a fishing ship, but they could pretend that attacks did their job and that the Canopus was useless.

The crew made the Canopus look as abandoned as possible. They made the old ship list (tilt) in the small harbor’s water and placed the cargo booms at odd angles. They hid oily rags in smudge pots near the blackened bomb holes so that smoke rose out of the ship for several days.

Japanese scouts saw a destroyed, abandoned ship. But, during the night . . .

Well, at night the ship came alive. Under Lt. Commander Goodall’s direction, the crew in the on-board machine shop worked tirelessly to create and repair weapons for the beleaguered American forces fighting on Bataan.

Despite the fact that the U.S.S. CANOPUS had been damaged by bombs and was partially beached at Mariveles, the work of repairing weapons and facilities was carried out at night and during non-flying weather. In these very important maintenance tasks and in and about the Section Base, Lieutenant Commander Goodall was exceptionally resourceful in manufacturing parts for extemporized weapons.

Citation on Henry Goodall’s Navy Cross award

Naval Battalion

With the Canopus safe from attack and relentlessly supporting on-shore troops, Lt. Commander Goodall found his services needed elsewhere.

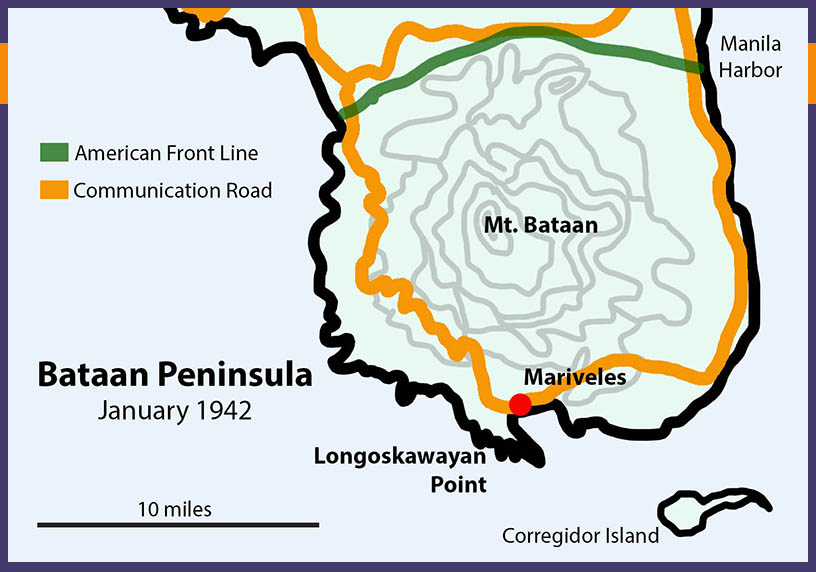

An Army Air Corps commander named Frank Bridget noticed that while Mariveles and the American front on Bataan were both well guarded, the Japanese could easily attack and cut off some 20 miles of a vital communication and supply road within short distance of the coast.

Cutting off that road would be disastrous to the American and Filipino resistance.

So, short on men and weapons, Bridget assembled the “Naval Battalion” — a somewhat rag-tag team of sailors and Marines. Lt. Commander Goodall was the Battalion’s second in command.

As Commander Bridget feared, Japanese troops landed at Longoskawayan Point and made their way inland toward the communication road, where the Naval Battalion met them and pushed them back to shore. But instead of fleeing, the Japanese hid in cliff crevices and caves along the coast near Longoskawayan Point. Their presence continued to threaten the American front lines.

Commanding the Mickey Mouse navy

The Naval Battalion and Canopus crew converted 3 of the ship’s small launches (boats) in to “Mickey-Mouse Battleships” — arming them with machine guns (some taken from destroyed American aircraft) and adding metal armor around the engines and guns.

As soon as the first launch was armed and armored, Lt. Commander Goodall led a small crew on a 6-mile cruise to Longoskawayan Point. Over the next couple of days, they bombed Japanese out of the shore caves and cliffs, even bringing back a few as prisoners.

With Longoskawayan cleared, the “Mickey Mouse” navy, now joined by 2 whaleboats, headed farther north on Bataan’s west coast to clear the shores and cliffs near Quinauan Point, where another Japanese landing party had infiltrated.

“During the entire operation,” explains Goodall’s Distinguished Service Cross citation, “Lieutenant Commander Goodall maintained an exposed position and directed in detail the maneuver and fire of all the boats in his detachment despite intense hostile fire from the beach and repeated bombing and strafing attacks by enemy dive bombers.

Returning from their mission on February 8, 1942, Goodall’s small navy encountered 4 Japanese bombers. The planes dove for the boats, while US sailors returned fire with on-board machine guns. Japanese bombs rained down, punching holes in the boats.

Goodall, his feet seriously wounded, ordered the American boats to shore and “calmly directed the care of other injured men.” 3 men were dead, 4 wounded.

The survivors fashioned stretchers and carried their brothers-in-arms through the Bataan jungle to the communication road. There they found an American truck driver who gave them a ride back to Mariveles, the Canopus, and (relative) safety.

For his actions, Lt. Commander Goodall received a Distinguished Service Cross and the Navy Cross — two of the highest military awards an individual can receive.

Marches, starvation, and torture

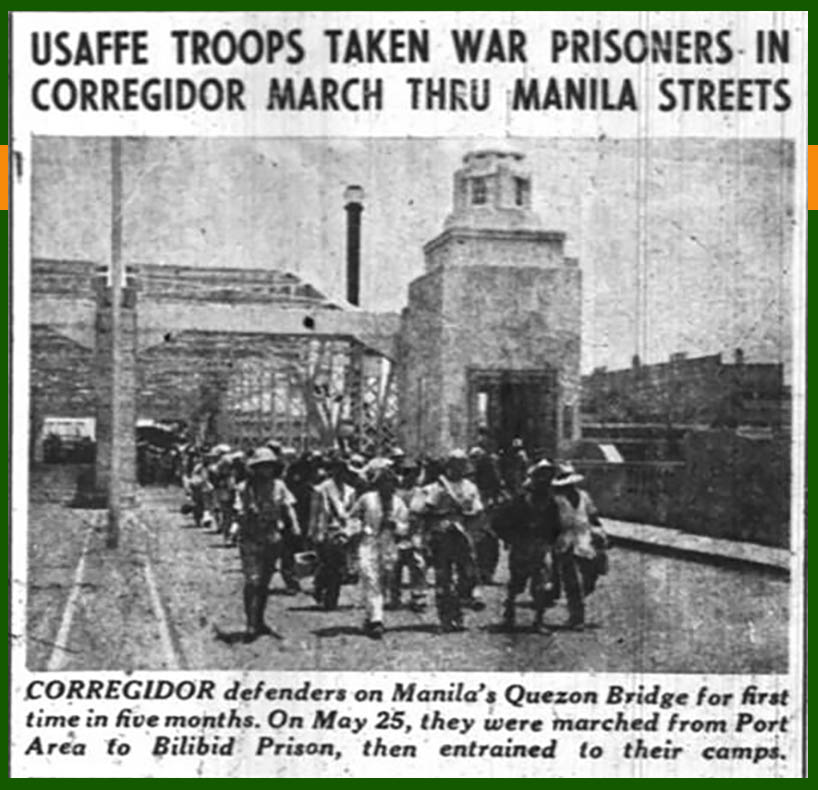

The wounded Goodall ended up on Corregidor, the American island fortress off the coast of Bataan. He became a prisoner of war on May 6, 1942, when the Japanese invaded Corregidor after months of siege and sustained bombing.

So started Goodall’s 33 months as a POW.

During that time, he joined the 1,000s of other American and Filipino POWs in a forced march through Manila en route to Cabanatuan POW camp 70 miles north of the city.

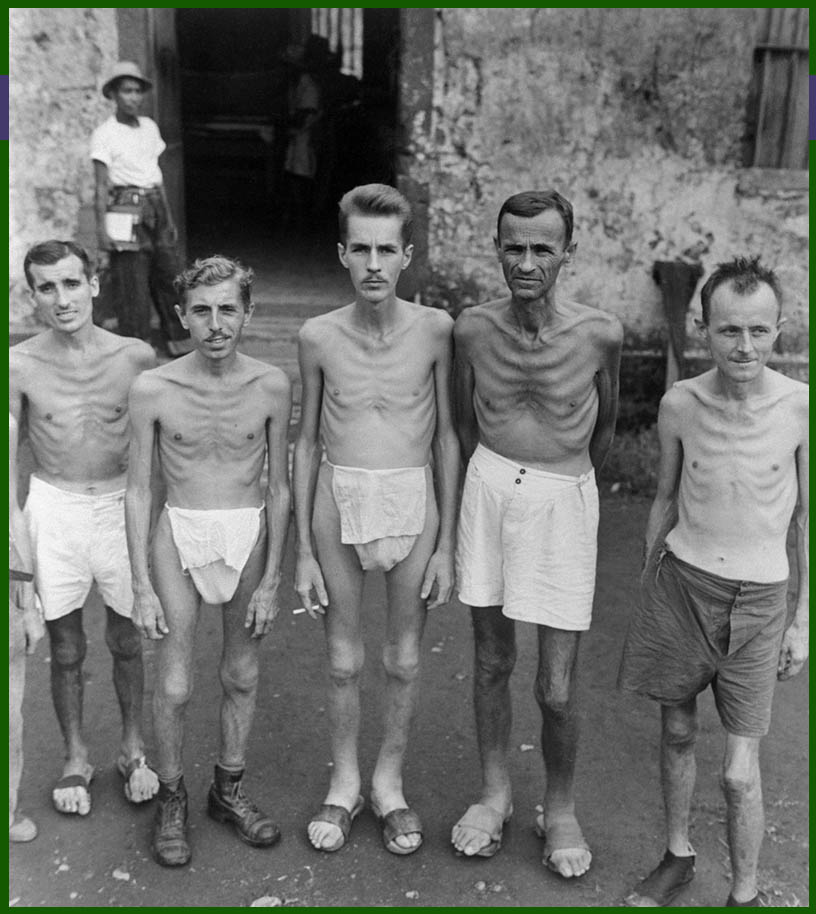

He likely spent the majority of his time at the Cabanatuan POW camps, although few records of his POW movements exist. Cabanatuan POWs endured starvation, diseases, beatings, and tortuous work camps.

The Yanks and tanks arrive in Manila

Nearly 3 years after capture, Henry Goodall found himself incarcerated at Bilibid Prison in Manila. The war had turned in the American’s favor and there had been heavy fighting, mainly by air, for several days. The hungry POWs at Bilibid eagerly awaited the “Yanks with tanks with steaks and cakes.”

At 11:45 am, on February 8, 1945 (almost 3 years to the day since Goodall had been wounded in the air attack), the Japanese guards left the prison because they “had been assigned another duty.” The POWs remained inside Bilibid for safety (since they were in the middle of a war zone) and even positioned their own guards to keep unwanted visitors out of the prison.

Around 6 pm, a rifle butt knocked a hole in one of the prison’s wooden shutters. Was it Filipinos? Or Japanese?

Both guesses were wrong.

American forces completely surrounded the prison walls, curious to know what was inside. They had assumed Japanese forces, but were surprised to find 1,200 POWs — 700 military and 500 civilians, including women and children.

The liberators passed cigarettes through the prison bars as they announced: “We’ve come to get you out!”

Post War

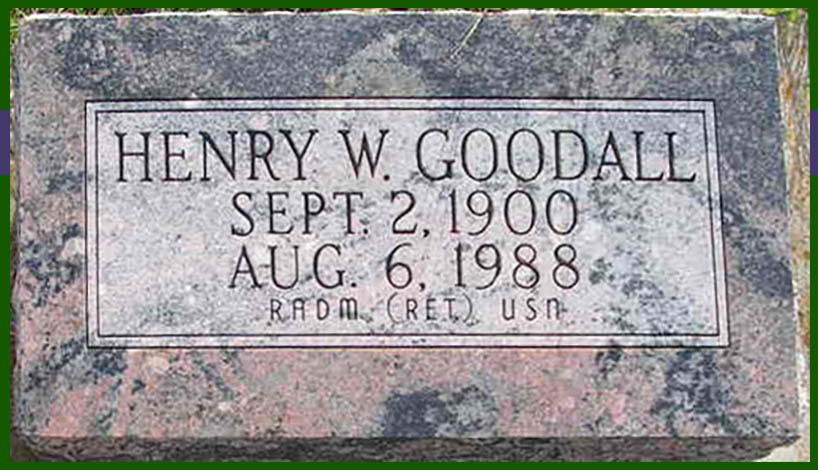

Goodall remained in the Navy after the war and eventually retired as a Rear Admiral.

He died on August 6, 1988, in San Diego, California, just one month before his 88th birthday, and only 3 months after his wife’s passing.

In the end, the hometown football star returned to Salina, Kansas. He rests in Gypsum Hill Cemetery near his parents and 2 siblings.

Read Next

Sources

- “Bilibid Liberation Roster,” found online at https://www.west-point.org/family/japanese-pow/BLR.htm, accessed 10 December 2019.

- Christina Goodall family, 1910 United States Federal Census [database on-line], Ancestry.com, original data from Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910 (NARA microfilm publication T624, 1,178 rolls), Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C., accessed 10 February 2020.

- Christina Goodal family, 1920 United States Federal Census [database on-line], Ancestry.com, images reproduced by FamilySearch, original data: Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920 (NARA microfilm publication T625, 2076 rolls), Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29, National Archives, Washington, D.C., access 10 February 2020.

- Earl LeRoy Sackett, chapters VI and VII, History of the Original USS Canopus, 1943, found online at http://as9.larryshomeport.com/html/chapter_vi.html, accessed 10 February 2020.

- Eugenia S Goodall entry, California, Death Index, 1940-1997 [database on-line], Ancestry.com, original data: State of California, California Death Index, 1940-1997, Sacramento, CA, USA: State of California Department of Health Services, Center for Health Statistics, accessed 10 February 2020.

- Henry Goodall entry, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918 [database on-line], Ancestry.com, original data: United States, Selective Service System, World War I Selective Service System Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, M1509, 4,582 rolls, imaged from Family History Library microfilm, accessed 10 February 2020.

- Henry William Goodall entry , U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935-2014 [database on-line], Ancestry.com, original data from Social Security Administration, Social Security Death Index, Master File, Social Security Administration, accessed 10 February 2020.

- Henry William Goodall entry, 1943 book, U.S., Select Military Registers, 1862-1985 [database on-line], Ancestry.com, original data: United States Military Registers, 1902–1985, Salem, Oregon: Oregon State Library, accessed 10 February 2020.

- Henry W Goodall family, 1930 United States Federal Census [database on-line], Ancestry.com, original data: United States of America, Bureau of the Census, Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930, Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1930, T626, 2,667 rolls, accessed 10 February 2020.

- Henry William Goodall entry, “Distinguished Service Cross WWII / Navy,” Home of Heroes: Medal of Honor and Military History, found online at https://homeofheroes.com/distinguished-service-cross/world-war-ii-distinguished-service-cross-recipients/distinguished-service-cross-wwii-navy/, accessed 10 February 2020.

- Henry W. Goodall entry, World War II Prisoners of War, 1941-1946 [database on-line], Ancestry.com, original data: National Archives and Records Administration, World War II Prisoners of War Data File [Archival Database], Records of World War II Prisoners of War, 1942-1947, Records of the Office of the Provost Marshal General, Record Group 389, National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD, accessed 10 February 2020.

- Henry William Goodall entry, California, Death Index, 1940-1997 [database on-line], Ancestry.com, original data: State of California, California Death Index, 1940-1997, Sacramento, CA, USA: State of California Department of Health Services, Center for Health Statistics, accessed 10 February 2020.

- Henry W. Goodall entry, U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007 [database on-line], Ancestry.com, original data: Social Security Applications and Claims, 1936-2007, accessed 10 February 2020.

- Memorial for RADM Henry William Goodall, Find a Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/22817340, accessed 10 February 2020.

- “New Bilibid Prison,” Wikipedia, found online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Bilibid_Prison, accessed 11 December 2019.

- Salina High School, 1919, Salina, Kansas, Ancestry.com, U.S., School Yearbooks, 1900-1999 [database on-line], accessed 10 February 2020.

- Sgt. Ike Thomas, “The Last Days of Bilibid,” found online at https://www.west-point.org/family/japanese-pow/Hudson%20Files/LastDaysBilibid.htm, accessed 10 December 2019.

- William Goodall family, 1900 United States Federal Census [database on-line], Ancestry.com, original data: United States of America, Bureau of the Census, Twelfth Census of the United States, 1900, Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1900, T623, 1854 rolls, accessed 10 February 2020.

Images

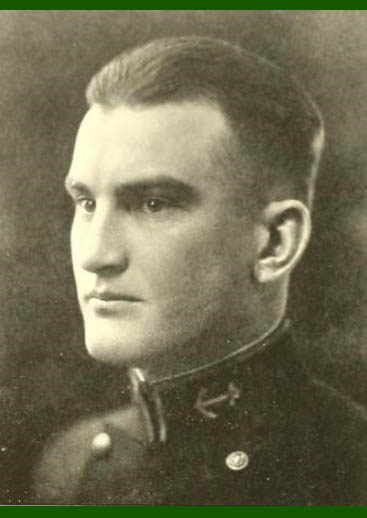

- Image 1. High school pictures. Salina High School, 1919, Salina, Kansas, Ancestry.com, U.S., School Yearbooks, 1900-1999 [database on-line], accessed 10 Feburary 2020.

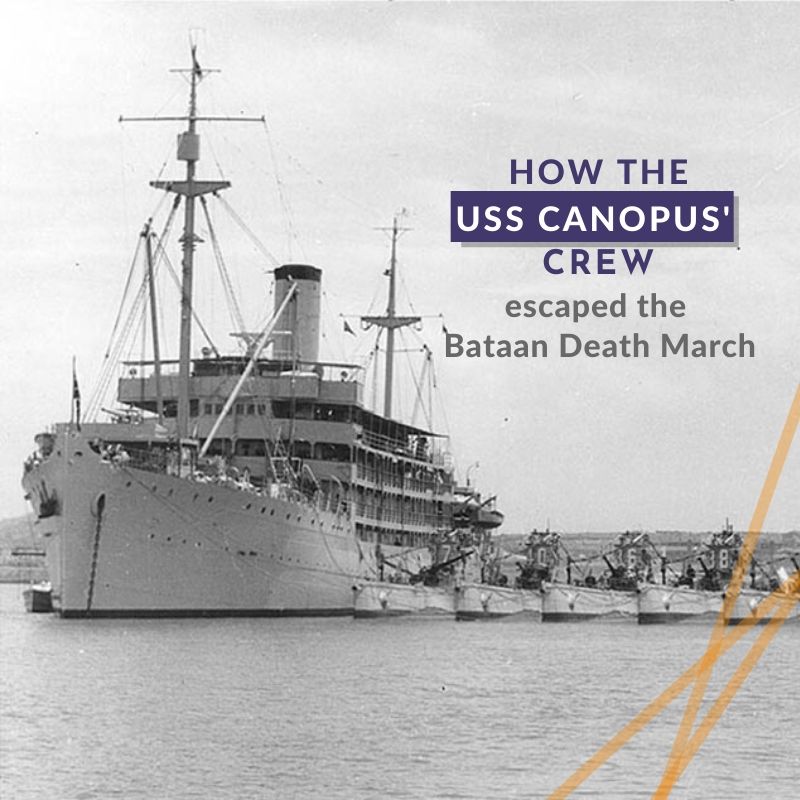

- Image 2. USS Canopus with submarines. Official US Navy image, image number 80-G-1014615, in the collections of the US National Archives and Records Administration, found online at Naval History and Heritage Command, Department of the Navy, https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/OnlineLibrary/photos/sh-usn/usnsh-c/as9.htm, accessed 19 August 2019.

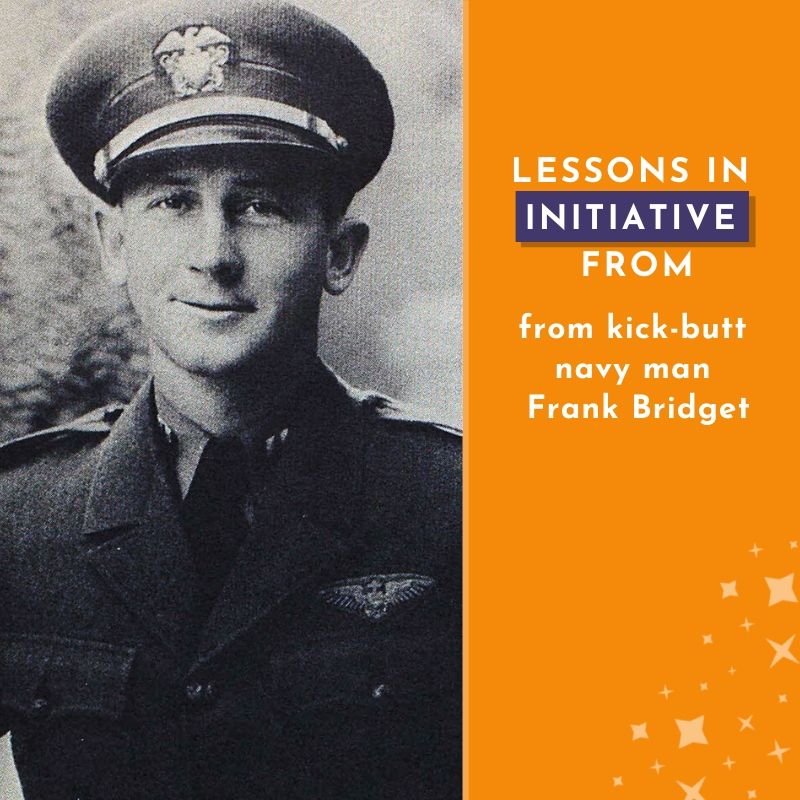

- Image 3. Goodall Navy portrait. Found on the memorial for RADM Henry William Goodall, Find a Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/22817340, accessed 10 February 2020.

- Image 4. Bataan map. Created by Anastasia Harman.

- Image 5. USS Quail. “The U.S. Navy minesweeper USS Quail (AM-15) in the Philippines,” US Navy photo, taken about 1930, Wikimedia Commons, found online at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:USS_Quail_(AM_15).jpg, accessed 11 February 2020.

- Image 6. Bataan coast line. Image licensed from Adobe Stock Images.

- Image 7. American POWs in Manila. From “USAFFE Troops Taken War Prisoners in Corregidor March thru Manila,” The Sunday Tribune, Manila, Philippines, 7 June 1942, page 3, found online at Pinterest, https://www.pinterest.com/pin/120682464999523850/?nic=1, accessed 15 October 2019. Note: This was a Japanese-controlled newspaper.

- Image 8. Bilibid Prison. Liberated POWs at Bilibid. Bettmann/Corbis photo found online at http://projects.wsj.com/lobotomyfiles/?ch=sidebar, accessed 10 December 2019.

- Image 9. Liberated Bilibid POWs. Liberated POWs at Bilibid. Bettmann/Corbis photo found online at http://projects.wsj.com/lobotomyfiles/?ch=sidebar, accessed 10 December 2019.

- Image 10. Goodall’s headstone. Found on the memorial for RADM Henry William Goodall, Find a Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/22817340, accessed 10 February 2020.