The early days of WW2 in The Philippines did not go well for American and Filipino forces.

Surprise Japanese air attacks beginning on December 8, 1941, all but decimated the American air forces in and around Manila and Bataan. Japanese ground troops quickly overran the island, and within mere weeks, that Americans and Filipino resistance had retreated to the Bataan Peninsula.

Such was the situation in January 1942, when a 44-year old naval aviator named Commander Francis “Frank” Bridget realized something.

A flaw.

An oversight.

An imperfection that could cost the Americans the war, or at least The Philippines.

Let’s set the stage — Bataan in Jan. 1942

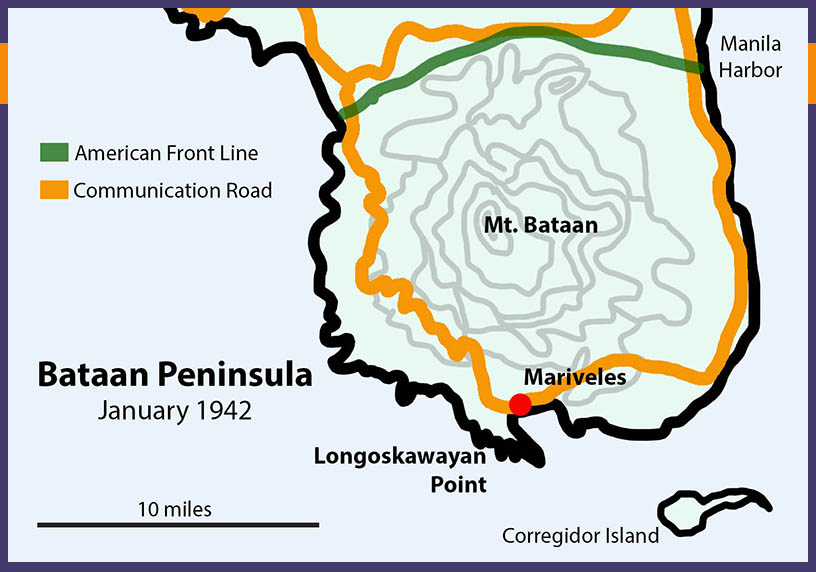

The American’s had amassed in southern Bataan. Their main stronghold was at Mariveles on the peninsula’s southern tip. American warships that had survived initial Japanese bombings at other Luzon naval bases retreated to guard Mariveles harbor.

American ground forces established a front about 20 miles north of Mariveles, and were keeping Japanese forces at bay — for the time being.

Between Mariveles and the front was a major obstacle — Mt. Bataan. The map above shows that the front on the northern slopes of the mountain, while Mariveles sits to the south.

A single road connected headquarters in Mariveles to the troops on the front. The road provided a major line of communication and supplies between those two crucial points.

And this is where Commander Bridget’s observation became so vital to American efforts on Bataan.

A prophetic observation

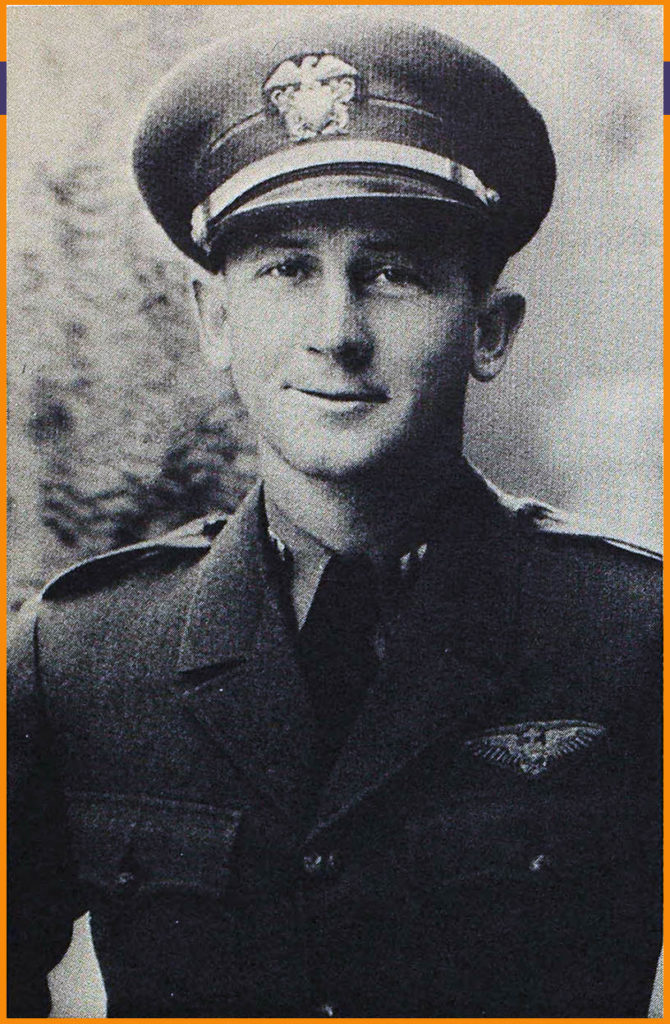

Francis Joseph Bridget entered this world on August 2, 1897, the 5th of 7 children born to Bernard and Josephine Bridget.

Frank graduated from the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, as an Ensign in 1921 and going into naval aviation. He married Charlotte Ballou in 1928, and their daughter Charlotte Bridget was born a little over a year later in 1929.

Throughout the 1920s and ’30s, he worked his way through the naval ranks. When WW2 came to The Philippines on December 8, 1941, Commander Bridget was a 20-year naval veteran with a front-row seat to the devastation of American aviation forces.

He became commander of the basically non-existent air forces on Bataan.

In surveying the American situation in Bataan, Bridget noticed that while Mariveles and the American front were both well guarded, some 20 miles of road within short distance of the sparsely guarded coast that could be sensitive to Japanese attack.

Cutting off that vial communications and supply line would be disastrous to the American and Filipino resistance.

Preventing Bataan’s early fall

“Frank was never one to sit back and criticize when action was needed,” recalled fellow Navy officer Captain Earl Sackett.

And taking action is exactly what Frank Bridget did.

He had about 150 naval aviation ground crewmen under his command. To them he added 330 sailors from various ships and bases and 120 Marines.

With these 600 or so men, Bridget organized the Naval Battalion, with Lt. Commander H. P. Goodall in second command, to prevent Japanese landings on the unprotected Bataan coast.

But . . . the thing is, sailors aren’t trained in ground combat. And, at least during WW2, they didn’t have weapons. At the very least, reported Captain Sackett, most “of the sailors knew which end of the rifle should be presented to the enemy . . . but field training was practically a closed book to them.”

So they first had to find weapons and equipment. They scavenged machine guns from destroyed aircraft and other places. And they dyed their Navy whites with coffee grounds to make them khaki colored and better suited for jungle fighting. (They actually ended up with bright yellow uniforms.)

The Marines assisted with training the sailors, which often times consisted of “watch them [the Marines] and do as they do.”

The Naval Battalion fights WW2 in The Philippines

Equipped and (kind of) trained, this band of sailor-soldiers headed into the Bataan jungle one day in late January 1942 for a training exercise — a hike to the coast to help “harden” them.

Except, well, before they got to the coast, they ran into American soldiers chased by Japanese infantry. The night before, just as Commander Bridget had predicted, Japanese troops landed off of Longoskawayan Point and made their way toward to that vital communication road.

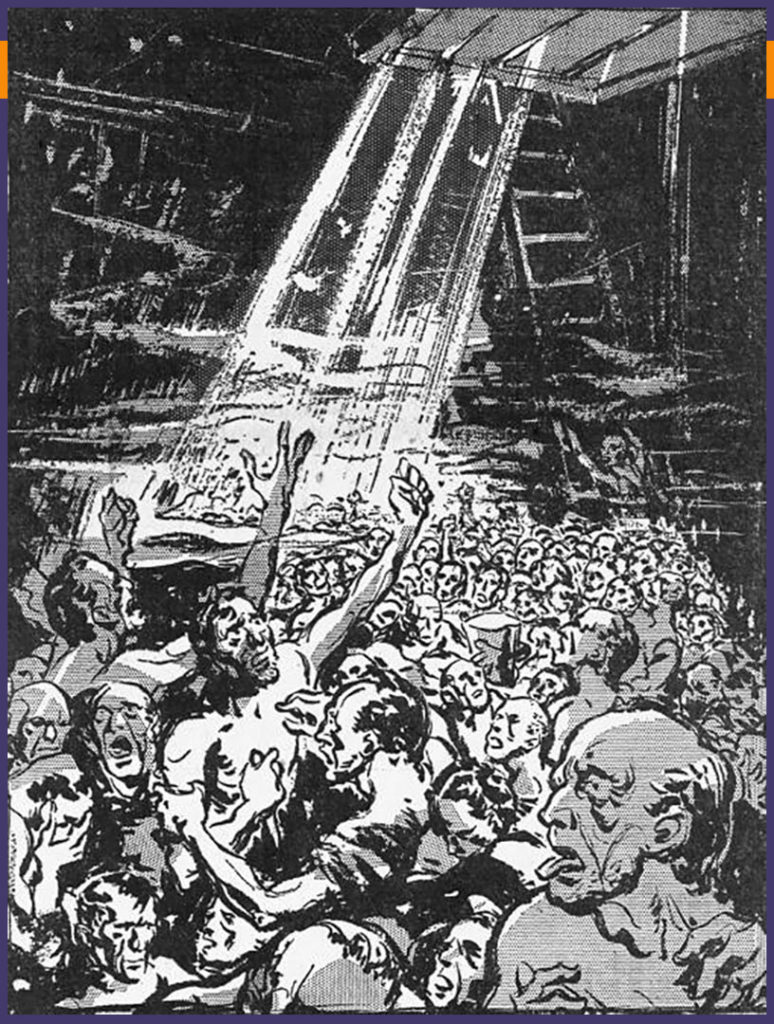

So hike turned into field training and, as Captain Sackett described, “Five days of what was probably the weirdest jungle fighting in the annals of warfare ensued.”

Any by-the-book fighting went out the window as the inexperienced-but-eager Naval Battalion attempted to stop the Japanese advance.

The Japanese soldiers had been especially chosen for this landing — they were larger and stronger than average soldier and well equipped for jungle fighting.

The untrained Naval Battalion didn’t even have food, extra ammunition, bedding, or medical supplies. They were loud. They wore bright yellow uniforms. Their companies couldn’t communicate with each other at night, allowing Japanese fighters to slip past their front.

But they fought. And the didn’t give up. They actually didn’t know enough about ground fighting to realize their case was fairly hopeless.

American “suicide squads” on Bataan

Their actions confused the Japanese.

One Japanese officer wrote in his journal about a “new type of suicide squads, which thrashed about in the jungle, wearing bright colored uniforms, and making plenty of noise. Whenever these apparitions reached an open space, they would attempt to draw the Japanese fire by sitting down, talking loudly, and lighting cigarettes.”

The Japanese also assumed that behind this front were well-stocked reserve forces, and their scouts frantically tried to find these reserves so they could know where best to take their invasion.

After 5 days of fighting, Filipino Scouts arrived to relieve the Naval Battalion. “I’ll take over now, Joe,” these scouts, natives of the island and well trained in jungle warfare, told the sailor-soldiers. They soon drove back that Japanese landing force.

Commander Bridget’s action had prevented Japanese forces from infiltrating southern Bataan, cutting off all American communication, and surrounding American forces. In essence, his foresight prevented the fall of Bataan in January 1942.

It earned precious time, the Americans hoped, for reinforcements to arrive and help push back the Japanese advance. Those reinforcements, however, were routed to other Pacific locations. And Bataan did fall a few months later.

Ordered to Corregidor

Returning from jungle fighting, Commander Bridget and the Naval Battalion then fitted smaller Navy ships with machine guns. They sailed the south eastern Bataan coast, looking for and destroying remnants of the Japanese landing party which had found shelter — with plenty of ammunition and food — in caves along the shore cliffs.

They continued using these retro-fitted ships to frustrate similar Japanese landings until the US Army was able to fortify the coasts.

With Bataan secured, Commander Bridget and the Naval Battalion followed orders to the island military fortress of Corregidor. There they joined the 4th Marines to protecting the island’s beach from enemy landings. But the Japanese did eventually land, on May 6, 1942, and Comm. Frank Bridget became a prisoner of war.

30 months as a POW

After spending several weeks in an oven-like, make-shift seaside POW camp, Bridget and the other POWs sailed to Manila where they were forced-marched and trained 70 miles north to Cabanatuan prison camp.

Bridget spent two and a half years — that’s 30 months — at the Cabanatuan camps. Conditions there were inhumane. Diseases ran rampant. The prisoners worked long hours, had very little food, and were beaten for infractions. He likely also spent time at the “inhuman hell hole” work camp Nichols Field.

Starvation, sickness, and heavy work took it’s toll on the prisoners. By late 1944, most POWs weighed less than 100 pounds. But the Japanese frequently transferred those prisoners well enough to work to other prison-work camps on Japan’s mainland.

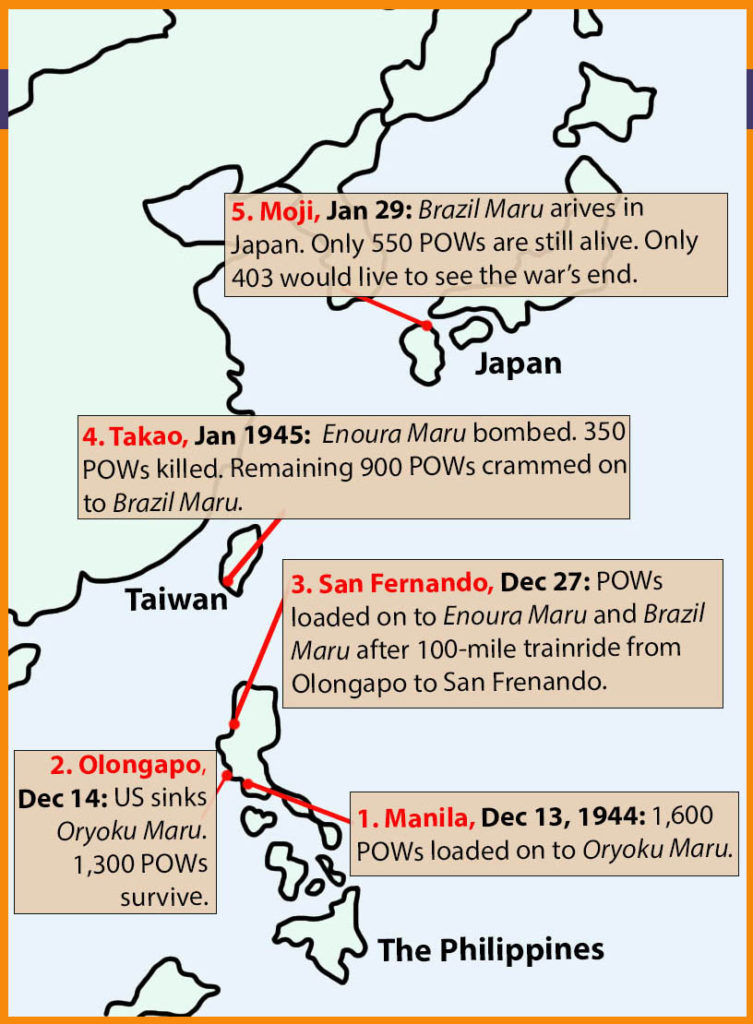

That’s why, on December 13, 1944, Commander Bridget entered the rear hold of the Japanese ship Oryoku Maru in Manila.

Surviving a shipwreck

The Oryoku Maru was a hell ship, because conditions were just that — hell. The Japanese crammed as many POWs as possible into the ship’s holds. There wasn’t enough air, food, or places to defecate.

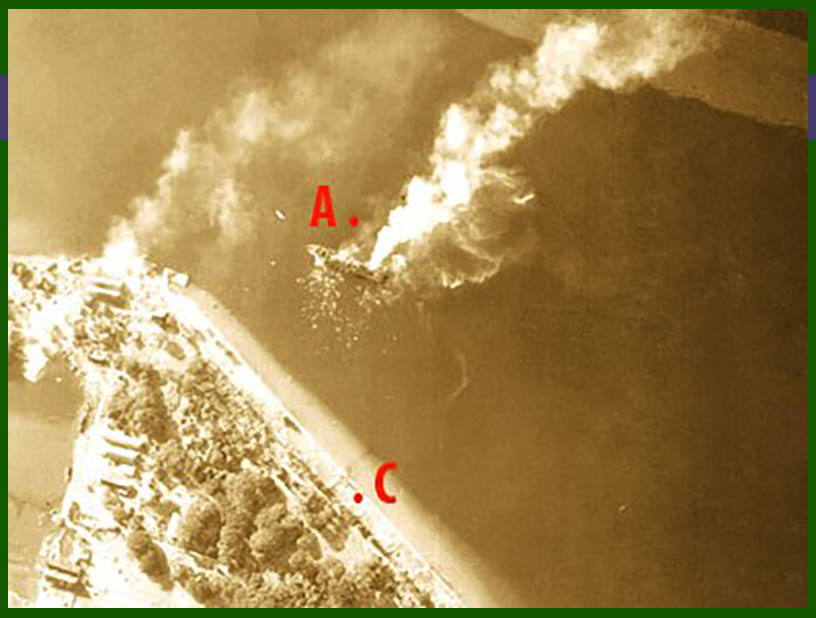

The Oryoku Maru had more than 1,600 POWs stuffed in to it’s 3 holds as it sailed around the Bataan Peninsula. 1,600 POWs. Remember that number, it’s important.

The ship wasn’t marked. So the US Navy planes had no way of knowing what cargo the enemy ship contained when they attacked the Oryoku Maru on December 15.

[Commander Bridget] warned that attempted escape [from the ship] might lead to a mass slaughter by the Japanese and calmly assured the frantic prisoners that if the vessel sank all would be able to abandon ship before it went down.

Citation from Capt. Bridget’s Legion of Merit

The ship did indeed go down. 1,300 POWs escaped the sinking ship and swam to shore at the Olongapo Navy Base.

Once on shore, Bridget and the other POW survivors spent several days on the base’s tennis court unprotected the scorching Philippine sun — with inadequate food and water — before being trained 100 miles north to San Fernando.

Hellish cruise to Japan

Here Frank Bridget entered another hell ship, which sailed from The Philippines on December 27, 1944.

Commander Bridget made every effort to maintain discipline among the [900] American [POWs] packed into the airless, humid holds of the ship, rendering valiant service in sustaining the morale of the starving, panic-stricken men. … [He could speak some Japanese and] repeatedly risked his life to go topside and endeavor to negotiate with the enemy to open ventilators, provide food and water, and alleviate the situation for his entrapped companions.

Citation from Capt. Bridget’s Legion of Merit

They reached present-day Kaohsiung, Taiwan (then Takao, Fermosa), on New Years Day 1945.

During their 2-weeks at Takao, Bridget and the other POWs were transferred to the ship Enoura Maru — another unmarked Japanese ship. And, again, American planes attacked the POW transport ship.

Although badly wounded, Bridget survived this second attack. He and other 900 survivors were all crammed into the Brazil Maru, which set sail for Japan.

When Brazil Maru arrived in Moji, Japan, on January 29, 1945 — 6 weeks after they sailed from Manila — only 550 POWs (of the original 1,600) remained alive.

Commander Bridget was not one of them. He had succumbed to his wounds in the filthy, inhumane hell ship conditions. He was 47.

Legacy

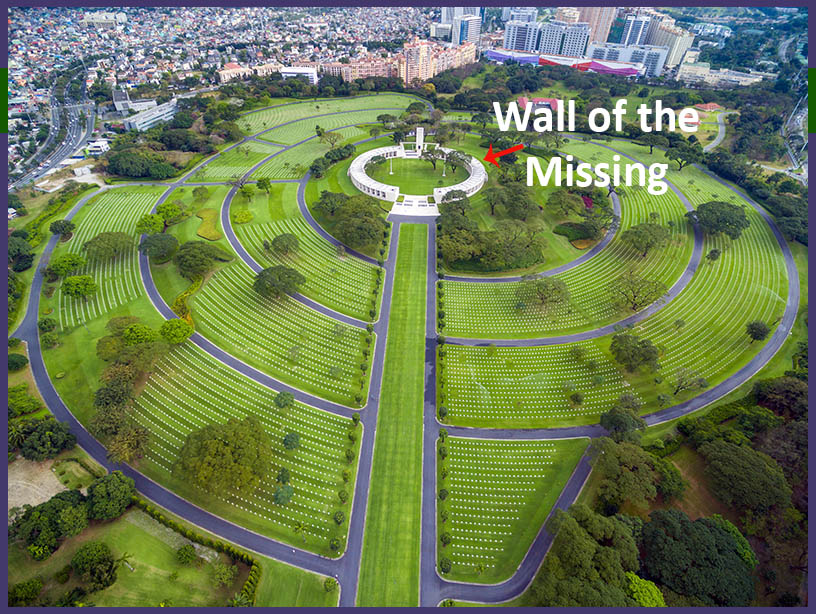

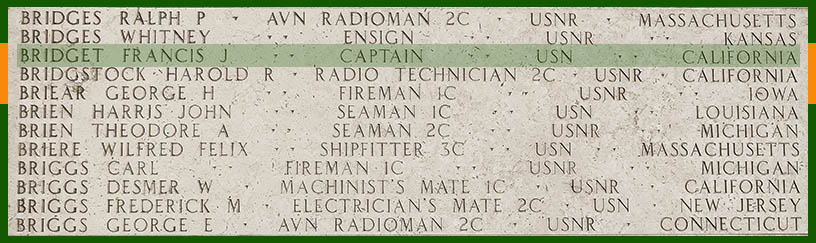

Commander Francis J Bridget is Missing in Action. As far as I can find, no one knows what happened to his body.

His name appears in a tablet on the Wall of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery, along side 36,285 other missing servicemen. In August 1945, Bridget was posthumously appointed to the rank of Navy Captain.

He received three major military awards — Navy Cross, Army Silver Star, and Legion of Merit — for his bravery and leadership during the Battle of Bataan and on-board the Japanese hell ships.

In 1956, the US Navy named destroyer escort USS Bridget in honor of his service and sacrifice.

His wife, Charlotte, died in 1980. She was buried at sea, per her request, perhaps to be with her husband. Their daughter, Charlotte, married and had 5 children. She died in 2011.

Read Next

Sources

- “Bridget, Charlotte Ballou,” Funerals, The San Francisco Examiner, Saturday, November 1, 1980, page B2, found online at Newspapers.com, accessed 27 January 2020.

- “Battle of Bataan,” Wikipedia, found online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Bataan, accessed 30 January 2020.

- “Captain Sackett’s History of the Original USS Canopus,” Chapters 6 and 7, Larry’s Home Port, found online at http://as9.larryshomeport.com/html/chapter_vi.html, accessed 29 January 2020.

- Francis Joseph Bridget marriage record, Ancestry.com. Florida, Marriage Indexes, 1822-1875 and 1927-2001 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2006. Original data: Florida Department of Health. Florida Marriage Index, 1927-2001. Florida Department of Health, Jacksonville, Florida, and/or Marriages records from various counties located in county courthouses and/or on microfilm at the Family History Library, accessed 2 January 2020.

- Francis J Bridget entry, Ancestry.com. World War II Prisoners of War, 1941-1946 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2005. Original data: National Archives and Records Administration. World War II Prisoners of War Data File [Archival Database]; Records of World War II Prisoners of War, 1942-1947; Records of the Office of the Provost Marshal General, Record Group 389; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

- Gabe Christy, “The Amazing Story Of James Crotty, Who Single Handedly Won The Coast Guard A Battle Streamer,” War History Online, found online at https://www.warhistoryonline.com/world-war-i/john-mccrae-officer-doctor-author.html, accessed 30 January 2020.

- James W. Erickson, compiler, “Oryoku Maru Roster,” found online at https://www.west-point.org/family/japanese-pow/Erickson_OM.htm, accessed 3 January 2020.

- “Manila American Cemetery and Memorial” brochure, American Battle Monuments Commission, found online at https://www.abmc.gov/cemeteries-memorials/pacific/manila-american-cemetery#cemetery-info-anchor, accessed 27 January 2020.

- Memorial for Capt Francis Joseph Bridget, Find A Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/56754567, accessed 28 January 2020.

- “Ōryoku Maru,” Wikipedia, found online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ōryoku_Maru, accessed 3 January 2020.

- USS Bridget Cruise Book, 1967, “U.S. Navy Cruise Books Index, 1918-2009,” database online, Ancestry.com, accessed 2 January 2020.

Images

- Image 1. Map of Bataan Peninsula. Created by Anastasia Harman.

- Image 2. Portrait of Francis Bridget. USS Bridget Cruise Book, 1967, “U.S. Navy Cruise Books Index, 1918-2009,” database online, Ancestry.com, found online at search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?db=navycruisebooksindex&<br/>h=383594&ti=0&indiv=try&gss=pt<br/>, accessed 2 January 2020.

- Image 3. Destroyed American plane. USAF Museum, found on “America’s First Ace of WWII,” http://fly.historicwings.com/2012/12/americas-first-ace-of-world-war-ii/, accessed 2 February 2019.

- Image 4. Southern Bataan landscape. Adobe Stock Photo, licensed by Anastasia Harman.

- Image 5. Japanese landing on Corregidor. Public domain, found online at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Correg-japanese-landing.jpg, accessed 2 June 2019.

- Image 6. Oryoku Maru with swimming POWs. US Navy photo, public domain, found online at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Oryoku_Maru_aerial_attack.jpg, accessed 11 July 2019.

- Image 7. Drawing of POWs on hell ship. From George Weller, “Death Cruise, Part 2: Yanks Go Mad on Agony Ship,” Chicago Daily News, November 9, 1945, found online at “News from the Past,” POW Resources, http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/newspaper/newsfrompast-cruiseofdeath.html, accessed 13 August 2019.

- Image 8. Oryoku Maru disaster map. Created by Anastasia Harman, January 2020.

- Image 9. Manila American Cemetery. Adobe Stock Photo. Licensed by Anastasia Harman.

- Image 10. Bridget Memorial Marker. “Francis J. Bridget,” American Battle Monuments Commission, found online at https://www.abmc.gov/node/497781, accessed 27 January 2020.

- Image 11. USS Bridget photo. “USS Bridget (DE 1024),” Navsource Online: Destroyer Escort Photo Archive, found online at http://www.navsource.org/archives/06/06021024.htm, accessed 27 January 2020.