Note: This post contains war-related content that some may find disturbing.

The relentless May sun made the pavement as hot as hell. But all POWs were required to march. Even the sick ones.

It was a rule enforced by the bayonet end of guards’ guns.

So malaria-ridden Ensign Harry Whitman stumbled his way through Manila that May afternoon in 1942. He was a newly captured prisoner of the Japanese. And, with some 10,000 other American POWs, was on parade through the country’s main city so that the Filipino populace would understand the Japanese victors’ might.

Being exposed to the blazing sun for some 4 miles worsened Whitman’s malaria symptoms. His marching companion, Alma Salm, took the burlap sack holding all the Ensign’s worldly belongings.

And that helped. A little. For a mile or so.

But Whitman’s fever worsened. He became delirious.

Despite fearing Japanese punishment, Salm pulled Whitman from the marching column. Laying the sick man on the hot graound, Salm covered him with an old raincoat and gave him some quinine (malaria medicine). Whitman shivered violently. Both men saturated in perspiration from their now 5-mile march in 90+ degrees.

Just as Salm predicted, Japanese guards were to them in moments, bayonets flashing in the unforgiving sun.

Ideal beginnings in Michigan

Harry Gill Whitman Jr.’s story begins 26 years before that dreadful march, in much an opposite place and time — Connecticut on October 20, 1915. He was the oldest of 5 children — 2 boys and 3 girls — born to Harry Sr and Emily Whitman.

Within a few years, the family relocated to Grand Rapids, Michigan, where Harry Jr. grew up and Harry Sr. was a Vice President for an asphalt company. The family did well, even having a live-in servant in the pre-Depression years. The Whitman’s were a well-known family in Grand Rapids.

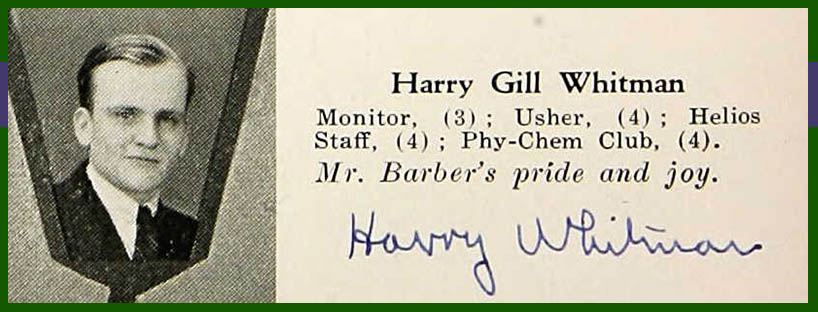

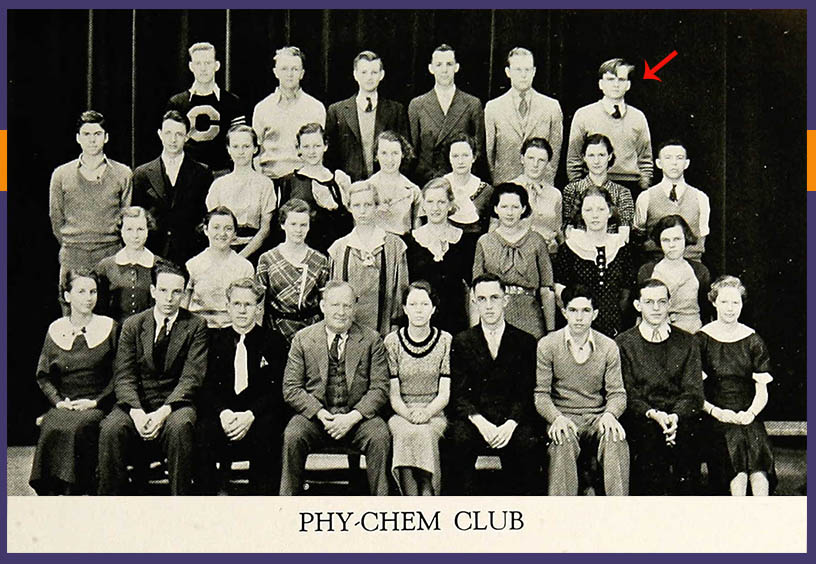

Harry joined the Central High School yearbook staff as well as the Phy-Chem club. In fact, young he was the “pride and joy” of that club’s adviser, Mr. Barber. Harry graduated high school in June 1934.

He attended junior college in Grand Rapids before transferring to MIT — yep, that MIT, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology — in Boston.

On October 15, 1940, 5 days before his 25th birthday and during his MIT senior year, Harry — and all US males ages 18-36 — registered for the WW2 draft. Commissioned an Ensign in the US Naval Reserves shortly before graduating from MIT in June 1941, he earned a BS in Engineering with an emphasis in Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering.

The first 25 years of Harry’s life seem blessed, as we sometimes say. But that was about to change, in at least 7 ways.

1. Stranded on an island hell

Two months after MIT graduation, in August 1941, Ensign Whitman began active duty. And two months after that, on October 24, 1941, he left Honolulu, Hawaii, on a ship bound for Manila in The Philippines.

He didn’t know it then, because the US was not yet at war, but it would be the last time he sailed as a free man.

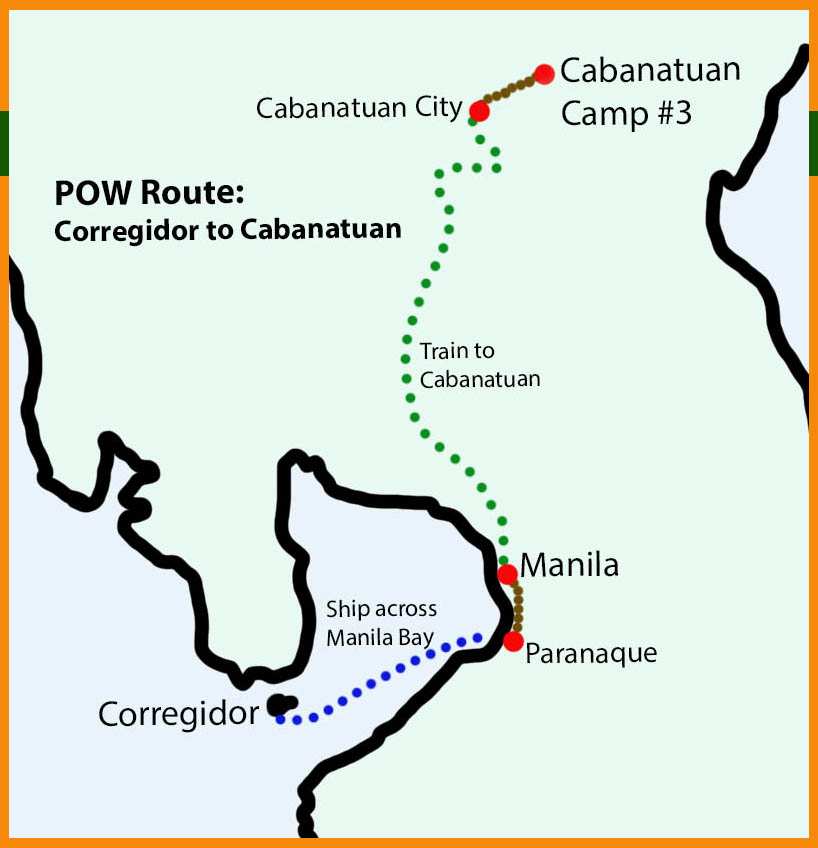

The US entered WW2 mere weeks after Harry arrived in The Philippines. He ended up on Corregidor island in Manila Bay, where he endured months of bombing, shelling, siege, sickness, and hunger before the Japanese finally captured the island on May 6, 1942.

Ensign Harry Whitman was now a prisoner of war.

2. A humiliating march…made worse

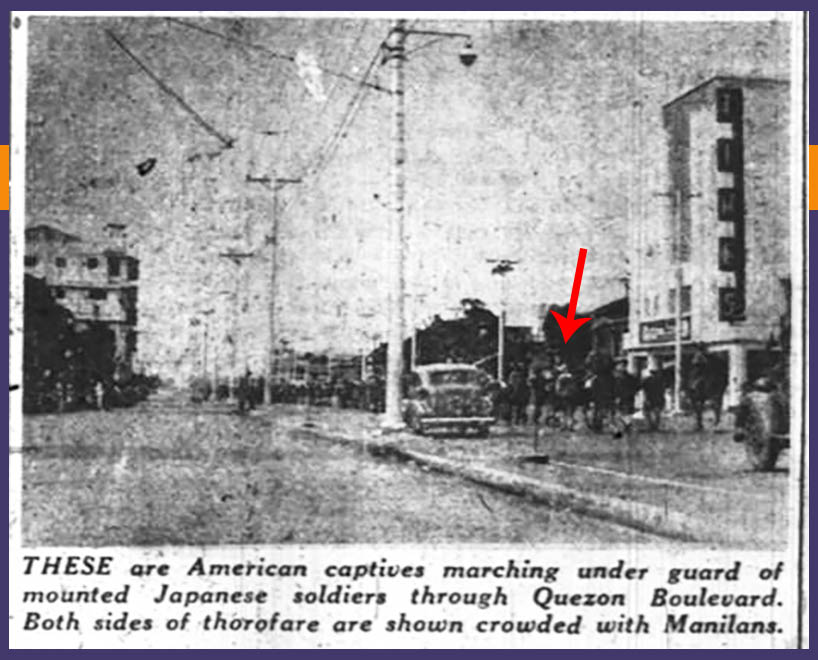

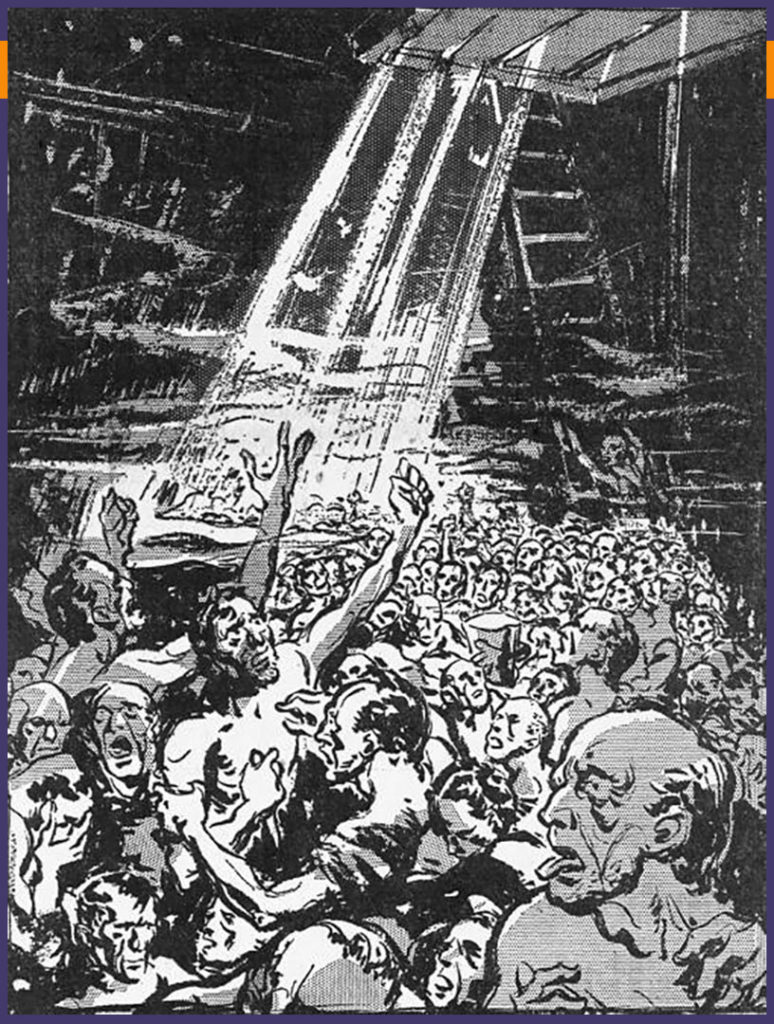

On May 24, 1942, en route to their permanent prison home, the POWs marched through Manila, in a show of Japanese might.

And it was during this 6-mile march that a feverish and delusional Ensign Whitman collapsed on the roadside with Alma Salm by his side. Soon the gun-and-bayonet-wielding Japanese guards arrived.

“I expected and was prepared for the usual violent physical treatment,” Salm explained of that moment.

But the Japanese surprised him. They felt the unconscious man’s forehead and, detecting fever, left Salm and Whitman alone.

When Whitman regained consciousness, Salm stealthily bought mango sherbet from a Filipino street vendor. The cold treat and rest restored Whitman a bit, until a Japanese truck picked the two men up and drove them to that night’s destination — Old Bilibid Prison.

But that day’s march, as rough as it was, paled by comparison to the journey’s remainder.

3. Train ride through hell…and beyond

Next morning, Japanese guards crammed Whitman, Salm, and the thousands of other POWs in to airless boxcars. 100 men per car. Standing room only. No food or water. No place to sanitary relieve the malaria-induced diarrhea so many suffered from. They were trained 75 miles north under the broiling Philippine sun to Cabanatuan City.

Here they spent the night in makeshift tents erected from salvaged tarps and raincoats.

The next morning, May 27, they began a 16-mile march to their new “home” — Cabanatuan POW Camp #3.

Again, the Japanese provided no food or water. Whitman and other POWs had to scavenge water from roadside ditches and mud holes during brief rests.

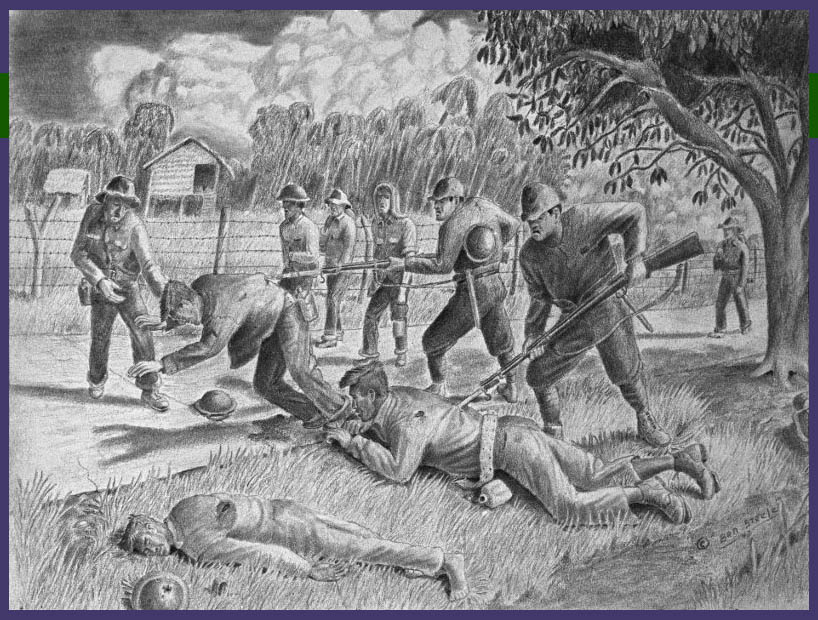

Sick, exhausted, hungry POWs fell to the ground. Some were left alone. Others prodded by the guards’ bayonets to get up and get moving.

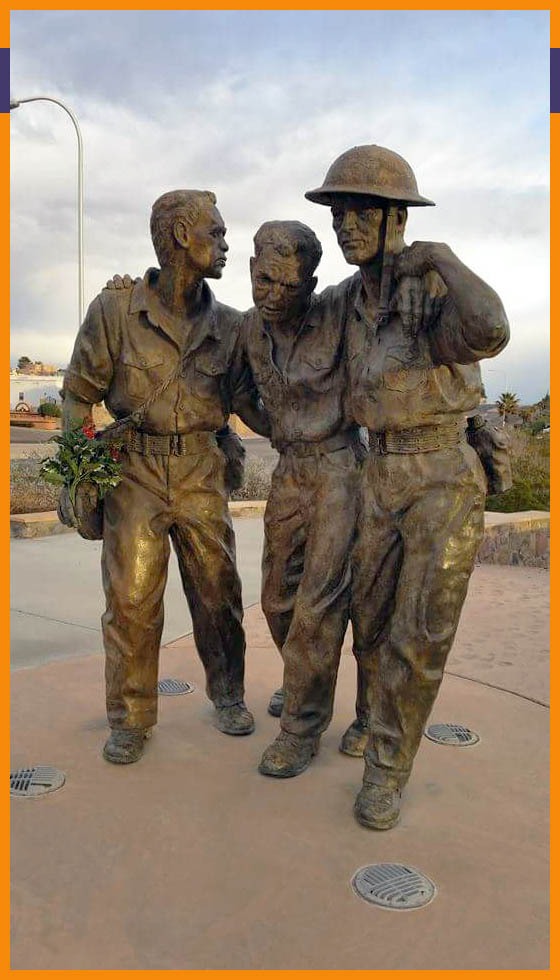

The humidity and heat only increased as the day went on. Not a breath of wind. Ensign Whitman’s fever spiked with another attack of malaria. He could hardly stand, and again Salm took Whitman’s pack.

But Whitman soon began stumbling and wavering and eventually leaned on Salm for support.

“He was a large husky fellow,” Salm recalled, “a former champion swimmer, and sustaining his weight plus carrying two packs was a little more than I could maneuver in my exhausted condition.” Salm himself was nearly 47.

Soon both men were on the verge of black out. Trying to ease the load, Salm reluctantly tossed away both packs — which held their blankets and minimal food.

But it made little difference.

“Finally my companion just slithered from me as I was unable to support him any longer,” said Salm. A Japanese guard jabbed Whitman with a bayonet, but he did not get up.

4. Consequences of an unconscious gesture

Mustering their remaining strength, Salm and another ailing POW hoisted Whitman up and half dragged him for a short distance. But Whitman’s protectors’ strength gave out completely at the bottom of a hill, and an unconscious Whitman again dropped to the ground.

The guards let him lay in the tall grasses at the road’s edge, a white flag marking his location.

“I felt pretty rotten about leaving Harry there,” Salm recalled, “but I knew a truck would pick him up eventually.”

Whitman opened his eyes sometime later to find a Japanese guard standing over him. Harry responded “with a pleasant look and slight smile on his face.”

It was the wrong move.

Taking that smile as an indication that Whitman had been pretending, the guard raised his bayonet and was bout to strike. Panicking, Whitman tapped his head, which helped the guard realize the Ensign was, indeed, a sick man.

Eventually a truck picked up Ensign Whitman and took him to Cabanatuan POW Camp #3.

5. Assigned to the inhuman, hell-hole work camp

Harry Whitman remained friendly with Alma Salm during his 30 months in prison camps.

Cabanatuan was a rough camp, with scarce food and medical attention compounded by copious disease and beatings.

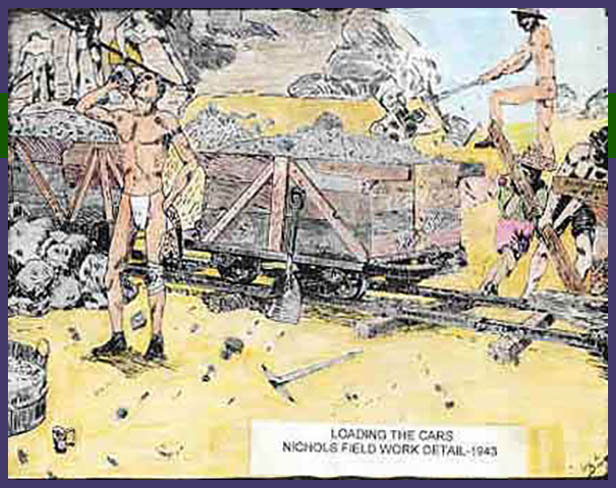

At some point, Whitman spent time at the inhuman hell-hole work camp of Nichols Field. The Japanese forced the sick and starving POWs to hand dig a new air strip. They dug the bottom of a hill until it collapsed, sometimes burying POWs alive.

“He was a splendid fellow,” Salm recalled, “and I enjoyed my associations with him. His hobby was ‘small’ boat building, and I sincerely hope he may return safely and enjoy the fulfillment of his plans of which he spoke to me often.”

Sadly, that hope wouldn’t be fulfilled.

6. Forced aboard the hell ship Oroku Maru

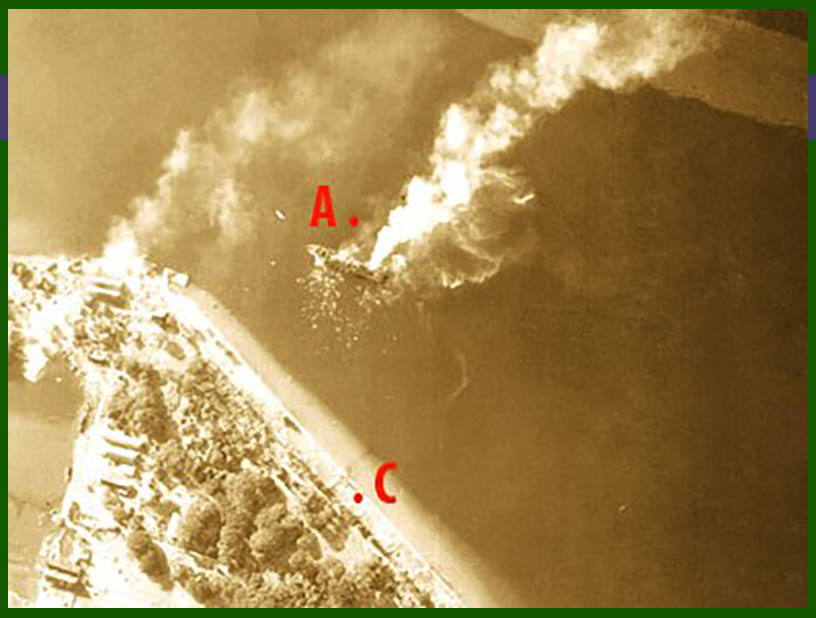

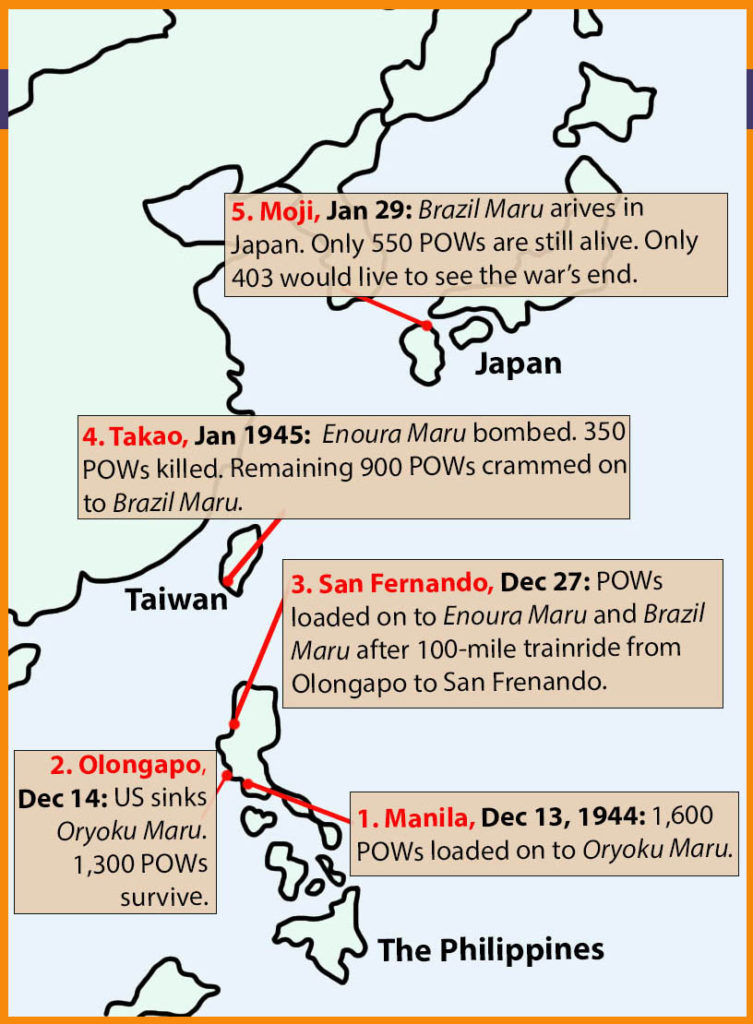

On December 13, 1944, Ensign Whitman entered the rear hold of the Japanese ship Oryoku Maru in Manila. The Japanese were transferring prisoners to camps in Japan.

More than 1,600 POWs were stuffed in to the ship’s 3 holds as it sailed around the Bataan Peninsula.

The ship wasn’t marked. So when they bombed it, the US Navy planes didn’t know what cargo the ship contained. Fortunately, 1,300 POWs — including Ensign Whitman — escaped the sinking ship and swam to shore at the Olongapo Navy Base.

Once on shore, Whitman and the other survivors spent several days on the base’s tennis court, unprotected from the scorching Philippine sun. Again, they had inadequate food and water. Eventually they were trained 100 miles north to San Fernando.

Here Harry Whitman entered either the Enoura Maru or the Brazil Maru, both of which sailed from The Philippines on December 27, 1944.

7. A hellish cruise to nowhere

Harry’s “hell ship” was overcrowded with sick, starving, dehydrated POWs. After 2.5 years of incarceration, many weighed under 90 pounds. That would have been a drop of some 100 pounds for the 5’9″ Whitman.

One colonel described the conditions:

Many men lost their minds and crawled about in the absolute darkness armed with knives, attempting to kill people in order to drink their blood or armed with canteens filled with urine and swinging them in the dark. The hold was so crowded and everyone so interlocked with one another that the only movement possible was over the heads and bodies of others.

Both ships reached present-day Kaohsiung, Taiwan (then Takao, Fermosa), on New Years Day 1945, where all the POWs were transferred to the Enoura Maru.

The ship was, of course, unmarked. And on January 9, 1945, American planes bombed it as it was anchored in Takao Harbor.

350 POWs died in the attack. Among them was Ensign Harry G. Whitman.

He was just 29 years old.

The Cabanatuan POW camp would be liberated only 21 days later. Alma Salm was among those rescued from that camp. He never knew what happened to his friend Harry.

Remembering Harry Whitman

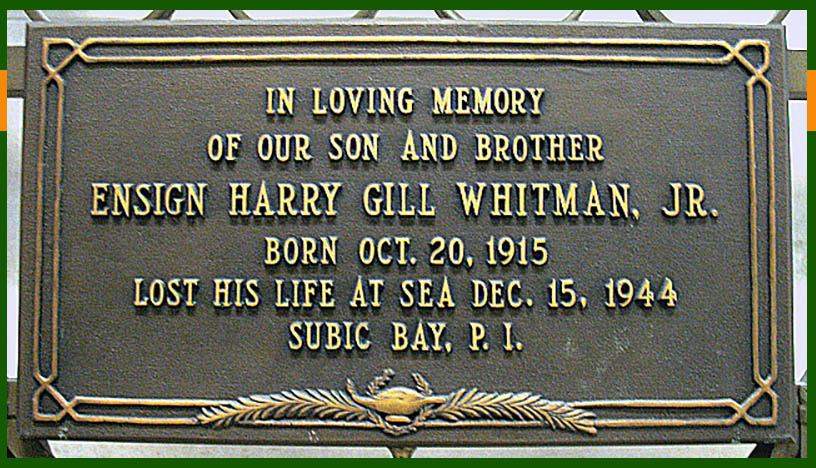

There’s conflicting information about when Harry died. Reports to his family said he died in the Oryoku Maru sinking on December 15. Other official documents specifically state he died in the Enoura Maru bombing.

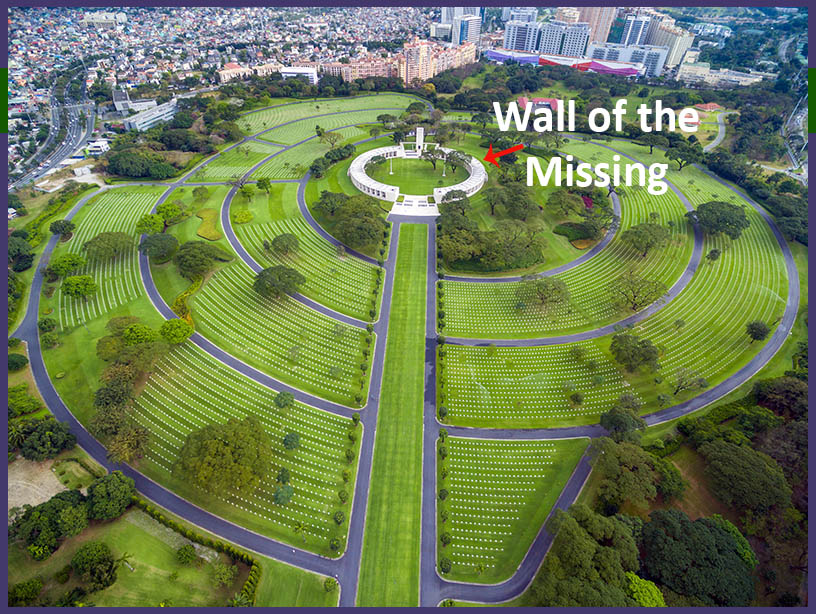

Either way, Harry’s name appears on the Walls of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery in The Philippines.

Back in MIchigan, Harry’s family placed their own memorial plaque at Graceland Memorial Park and Mausoleum in his hometown of Grand Rapids.

After his death, Whitman received the Purple Heart.

Harry’s only brother was a member of the Army Air Corps in Africa during WW2. He returned home, married, and eventually had a son — who he named Harry Gill Whitman.

Read Next

Sources

- “1920 US Federal census,” database online, entry for Harry Whitman, Ancestry.com, accessed 20 October 2011

- “1930 US Federal Census,” database online, entry for Harry G Whitman, Ancestry.com, accessed 20 October 2011.

- Degree Candiddiates at MIT, Boston Globe, 10 June 1941, page 4, Newspapers.com, accessed 15 April 2020.

- Ens Harry Gill Whitman Jr memorial, Find A Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/97285795, accessed 15 April 2020.

- Harry G Whitman Jr, passenger list for SS President Harrison, departing Honolulu, Hawaii, 24 October 1941, Honolulu, Hawaii, Passenger and Crew Lists, 1900-1959, database online, Ancestry.com, Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving or Departing at Honolulu, Hawaii, 1900–1954, NARA Microfilm Publication A3422, 269 rolls; A3510, 175 rolls; A3574, 27 rolls; A3575, 1 roll; A3615, 1 roll; A3614,80 rolls; A3568 & A3569, 187 rolls; A3571, 64 rolls; A4156, 348 rolls. Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, Record Group 85. National Archives, Washington, D.C., Passenger and Crew Manifests of Airplanes Departing from Honolulu, Hawaii, 12/1957-9/1969, NARA Microfilm Publication A3577 56 rolls. Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787-2004, Record Group 85. National Archives, Washington, D.C, accessed 14 April 2020.

- Harry Gill Whitman, U.S. WWII Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947, database online, Ancestry.com, accessed 14 April 2020.

- Harry G Whitman Sr family, 1940 United States Federal Census, database online, Ancestry.com, original data: United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1940. T627, 4,643 rolls, accessed 15 April 2020.

- “Helios 1934,” Central High School, Grand Rapids, Michigan, pages 32 and 47, in “US Yearbooks,” database online, entry for Harry G Whitman, Ancestry.com, accessed 23 October 2011.

- Franklin Pierce Whitman memorial, Find a Grave, found online https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/81171531, accessed 16 April 2020.

- “World War II Prisoners of War, 1941-1946,” database online, entry for Harry G Jr Whitman, Ancestry.com, accessed 23 October 2011.

- “Oryoku Maru,” Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oryoku_Maru, accessed 22 October 2011.

- Erickson, James W., “Oryoku Maru Roster,” January 2007, online at http://www.west-point.org/family/japanese-pow/Erickson_OM.htm, accessed 23 October 2011.

- “US Rosters of WWII Dead, 1939-1945,” database online, entry for Harry G Whitman Jr, Ancestry.com, accessed 23 October 2011.

- “World War II and Korean Conflict Veterans Buried Overseas,” database online, entry for Harry G Whitman Jr, Ancestry.com, accessed 23 October 2011.

- Harry Whitman memorial on Wall of the Missing. “Harry G Whitman,” American Battle Monuments Commission, found online at https://www.abmc.gov/decedent-search/whitman%3Dharry, accessed 16 April 2020.

- “US Rosters of WWII Dead, 1939-1945,” database online, entry for Harry G Whitman Jr, Ancestry.com, accessed 23 October 2011

- “World War II Prisoners of the Japanese, 1941-1945,” database online, entry for Harry G Whitman Jr, Ancestry.com, accessed 23 October 2011.

- “Purple Heart,” Wikipedia, accessed 23 October 2011.

Images

- Image 1. Harry Whitman’s senior picture. “Helios 1934,” Central High School, Grand Rapids, Michigan, page 32, in “US Yearbooks,” database online, entry for Harry G Whitman, Ancestry.com, accessed 15 April 2020.

- Image 2. Central High School Phy-Chem Club. “Helios 1934,” Central High School, Grand Rapids, Michigan, page 47, in “US Yearbooks,” database online, entry for Harry G Whitman, Ancestry.com, accessed 15 April 2020.

- Image 3. POWs marching through Manila. From “USAFFE Troops Taken War Prisoners in Corregidor March thru Manila,” The Sunday Tribune, Manila, Philippines, 7 June 1942, page 3, found online at Pinterest, https://www.pinterest.com/pin/120682464999523850/?nic=1, accessed 15 October 2019.

- Image 4. POW route from Corregidor to Cabanatuan. Created by Anastasia Harman, 2019.

- Image 5. POWs on Bataan Death March. Drawing by Ben Steele, from Tragedy of Bataan, found online at http://www.tragedyofbataan.com/bsteele/, accessed 16 October 2019.

- Image 6. Bataan Death March Memorial. Taken by Kris Punke, Wikimedia Commons, found online at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bataan_Death_March_Memorial_Las_Cruces_NM.jpg, accessed 16 October 2019.

- Image 7. POWs at Nichols Field. Drawing courtesy Al McGrew, H Company, 60th CAC, who was captured on Corregidor, found on http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/philippines/nichols_pasay/nichols_plot.html, accessed 2 February 2019.

- Image 8. Oryoku Maru with swimming POWs. US Navy photo, public domain, found online at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Oryoku_Maru_aerial_attack.jpg, accessed 11 July 2019.

- Image 9. Route of Oryoko Maru disaster. Map created by Anastasia Harman, 2020.

- Image 10. Drawing of POWs on hell ship. From George Weller, “Death Cruise, Part 2: Yanks Go Mad on Agony Ship,” Chicago Daily News, November 9, 1945, found online at “News from the Past,” POW Resources, http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/newspaper/newsfrompast-cruiseofdeath.html, accessed 13 August 2019.

- Image 11. Burning Enoura Maru. Overhead strike photo of bomb splashes and burning ships in Takao harbor (Kaohsiung) on Formosa (Taiwan), Jan 9, 1945, United States Navy via USS Hornet, public domain, World War II Database, found online at https://ww2db.com/image.php?image_id=21698, accessed 16 April 2020.

- Image 12a. Harry Whitman memorial on Wall of the Missing. “Harry G Whitman,” American Battle Monuments Commission, found online at https://www.abmc.gov/decedent-search/whitman%3Dharry, accessed 16 April 2020.

- Image 12b. Photo Licensed from Adobe Stock Images.

- Image 13. Harry Whitman Memorial marker in Grand Rapids. Ens Harry Gill Whitman Jr memorial, Find A Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/97285795, accessed 15 April 2020.