Daniel Moore left his family.

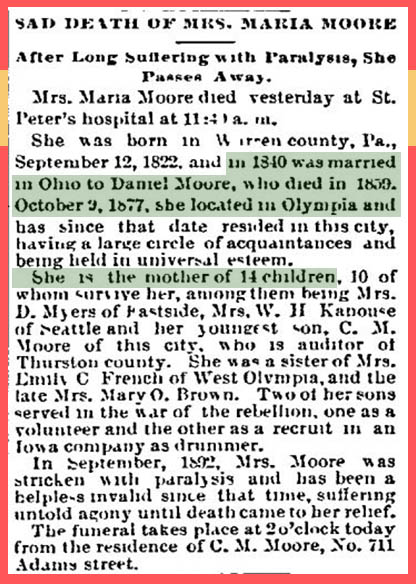

After 30 years of marriage, his wife and their youngest kids moved west to Washington state in the 1870s. Daniel Moore, who never treated his wife very well, didn’t come with them. He stayed in Chicago.

In 1884, one of his sons visited Chicago and reported that “Grandpa Peanuts” (Daniel’s nickname) was in good health.

At least . . . that’s how the family story goes.

Family stories fascinate me. On the one hand, they bring our people to life and add interesting details to family trees. On the other hand, well, they can be total crocks.

So how can you separate fact and fiction in family stories, myths, rumors?

I’ve got 5 ways to help you.

1. Write down what you know

Collect and write down all the stories, facts, rumors, info you’ve heard about an individual or family. If you know where or who the info comes from, include that as well. You want to know where info comes from — even if it’s just that great-aunt Margie always told this story.

The Daniel Moore story I told above comes from one place — this document written by Daniel’s great-granddaughter Mimi.

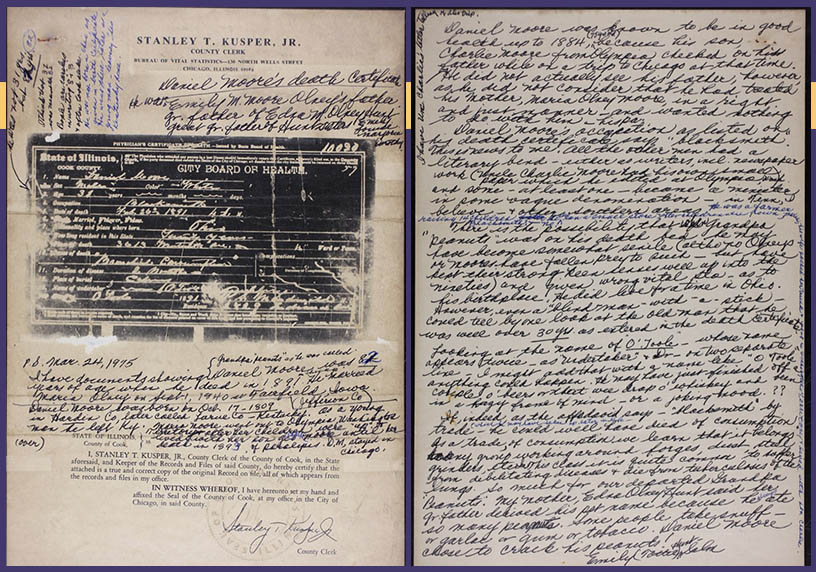

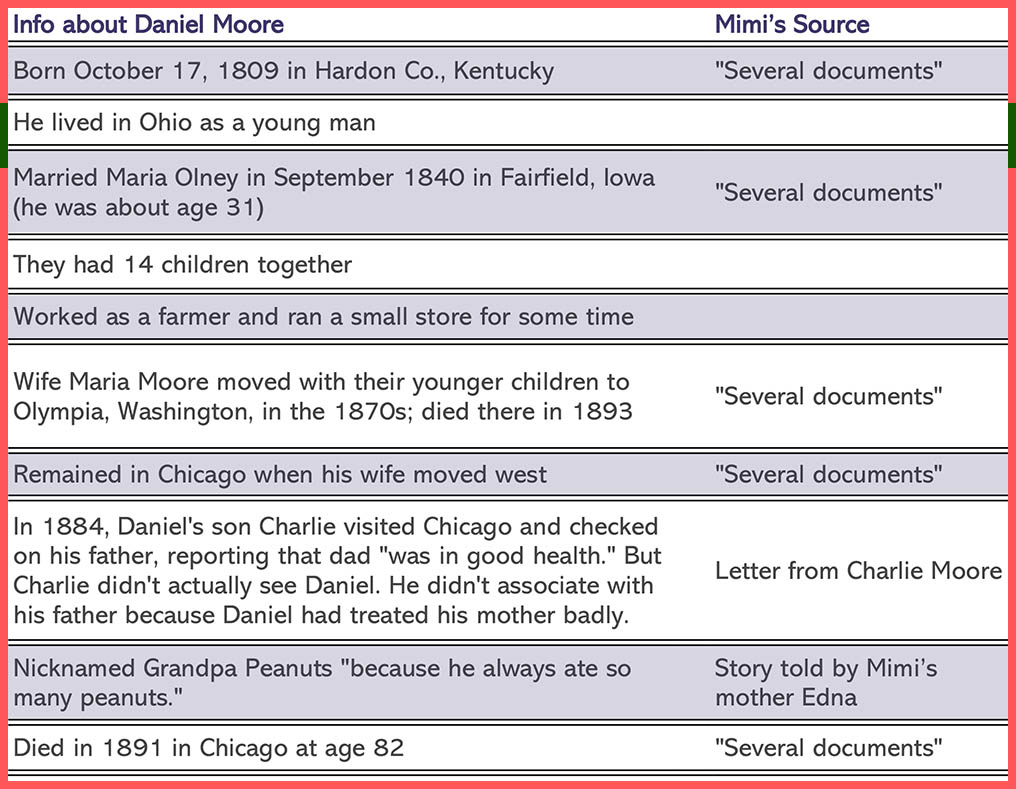

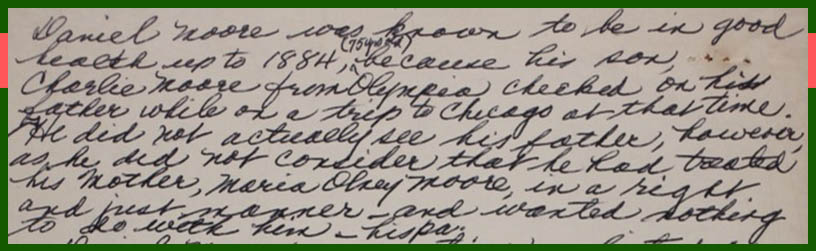

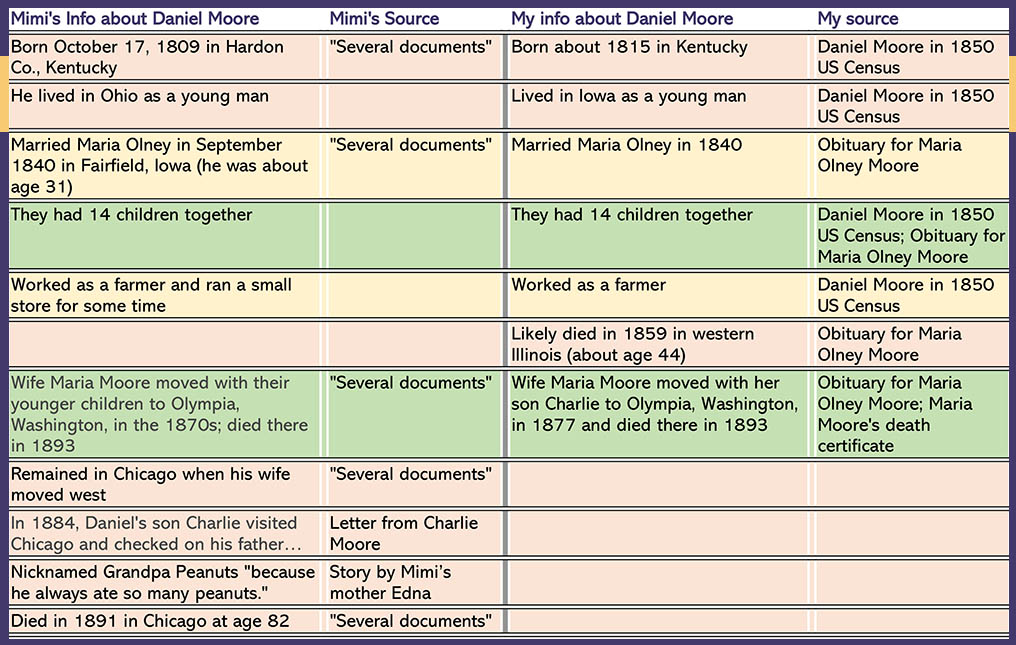

I know you can’t read that. So I’ve pulled out the info we learn about Daniel Moore from this document, as well as Mimi’s source for said info:

Sadly, while Mimi’s note and information about Daniel Moore has been passed down, none of her supporting docs, letters, or oral histories came along. And she didn’t provide enough source information for others to be able to retrace her research tracks.

So, without good documentation, I’m not certain what information about Daniel Moore is fact and what is fiction.

2. Is the source reliable?

Consider whether you really can/should trust the sources for the stories, info, and so.

What’s a source? A historic document. A family member’s verbal story or letter. Info from another family history researcher. Or any other place the story/info came from.

People sources

Remember that a family member’s information is only as good as, well, them.

Sometimes humans exaggerate, get confused, forget things, boast, lie, or make mistakes. When we combine human nature with family story, we get, well, family rumors.

So if you know that Great-Aunt Margie exaggerates everything, then that family story about her grandfather being a NASA test pilot may not be 100% accurate.

Let’s apply this to the Daniel Moore Case Study:

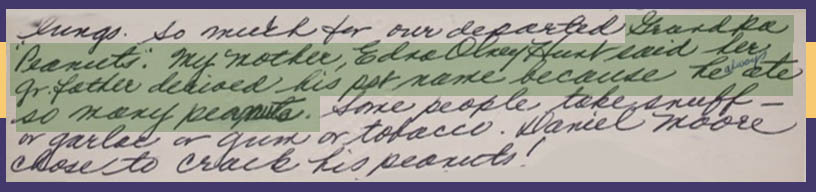

Mimi claims that her mother Edna (Daniel Moore’s granddaughter) told her that Daniel Moore was called “Grandpa Peanuts,” because he was always eating peanuts.

This is a fantastic piece of information — if it’s true.

But I have documents suggesting that Daniel Moore died in 1859, not in 1891 as Mimi claimed (I’ll explain more below). 1859 was some 15 years before Edna was born, and Daniel did not have any grandchildren at that time. So it would be strange for him to be called Grandpa anything.

And if that really were his nickname, then the story would have been told to Edna, who told it to Mimi, who shared it with me. So that’s 3rd- or 4th-hand information . . .

So I’m now wondering if Grandpa Peanuts was actually Edna’s other grandfather (her dad’s dad) and that someone got confused about who the nickname belonged to.

Document sources

Here’s an important research principle — the farther away a document was created from an actual event, the more likely the information is NOT correct.

Death certificates, for example, are usually created when a person dies, so the information about the death date, place, and manner of death is likely accurate.

However, some death certificates include information about the deceased person’s parents, birth date and place, and similar. And that info is provided by an informant — who may or may not know much about the deceased person’s past. So birth information on a death certificate might be false.

Other researchers

When considering family information from another researcher, evaluate whether you can trust the researcher’s conclusions. If you find major errors in another researcher’s work, I’d suggest suspecting all his/her work.

In the Daniel Moore case study:

I’ve determined that I can’t trust my great-grandmother Mimi’s research conclusions. She found the wrong death certificate for Daniel Moore, but infamously insisted it was absolutely his. (You can read it here. Her conclusions are 100% worth it! 🤣)

And since all the information about Daniel Moore came from Mimi, I don’t trust that everything we “know” about him is correct.

Does it mean everything Mimi shared about Daniel is wrong? Not at all. But it does mean I’m going to be very careful in what I add to my family tree.

3. Is the info plausible?

My Robeson family, I’ve been told, were tailors for the king of England.

Wow! How cool! But . . .

Is it plausible?

Maybe, but I suspect this is an exaggeration. Perhaps a Robeson once made a hat that the king bought. Or maybe it was the king’s butler’s father who bought the hat. But after 100+ years of retelling, the story has shifted to the Robeson’s being the royal tailors.

Run family stories and info through your internal BS filter. If the story seems a little too grand, over-the-top amazing, or in any way suspect, take a closer look.

In the Daniel Moore case

Daniel’s son supposedly visited Chicago and learned that dad “was in good health.” Except, the story also says that the son didn’t actually see Daniel.

Hmmm. That’s suspicious to me.

If the son didn’t see Daniel, how did he know Daniel was in good health? Mimi claims to have a letter from son Charlie recounting this trip, but no one else has seen the letter. I just don’t know how much I can trust this piece of information.

Also, stories tend to shift, shorten, and intensify with retelling. These changes lead to implausible stories.

Compare the story I told about Daniel Moore at the beginning of this article with the table under step 1. Notice how my version is shifting and losing details Mimi “knew” about him.

4. Is the story a common myth or historically inaccurate?

There are several common family history myths, such as:

- They changed our family’s name at Ellis Island (Names weren’t changed at Ellis Island. Period. It never happened.)

- Our great-great-grandmother was an Indian Princess (Native American tribes don’t have princesses.)

- 3 brothers came to America from [insert country]. When they got here, one went north, one went west, and one went south. (And then Harry Potter found all 3 Deathly Hallows…)

- Learn more myths and explanations in this Family Tree magazine article.

Be skeptical of any common myths you discover in your family stories.

Similarly, make sure claims of your family’s participation in historical events actually fit within the time frame of that event happening.

Great-grandma Helen couldn’t be a Titanic survivor if she died in 1911 — the ship sank in 1912. She very well may have survived a ship wreck, but it wasn’t the Titanic.

5. Do the research yourself

If ideas 1-4 leave you with questions about a family story — it’s time do the research yourself.

Because of our many questions about Mimi’s research. My dad and I have spent a lot of time researching Daniel Moore. Here’s a comparison of what we’ve learned vs. Mimi’s info:

You’ll notice

- My dates and places about Daniel Moore’s life are not as specific as Mimi’s. I haven’t found many documents with specific dates and places for his life events. I don’t know where Mimi found those specific dates.

- Some facts are the same or very similar.

- The docs I’ve found suggest Daniel Moore died in 1859, leaving his wife to raise their children (ages 1-17) alone.

My Daniel Moore Theory

So, if Daniel did die in 1859, then all the reported stories about him staying Chicago, him treating his wife poorly then leaving her, a son “visiting” him in Chicago, and him being called Grandpa Peanuts . . . well, it’s wrong.

Where did those stories come from? I honestly don’t know.

I do believe that Mimi found several documents that she believed were about her great-grandfather — but not all were about them. (For example, check out her analysis of Daniel Moore’s 1891 death certificate.)

But the letter son Charlie wrote about checking up on his father in 1884? And Edna’s story about calling Daniel Moore Grandpa Peanuts? I’m not certain where they came from.

Mimi could be misremembering or making things up. Edna could have confused which grandfather she called Grandpa Peanuts. Charlie could have been talking about someone else in his letter.

But whatever the case, it’s apparent that Daniel Moore wasn’t the deadbeat dad I made him out to be at the beginning of this article.

It actually looks like there was a family tragedy (Daniel and Maria’s infant son died the same year as he did) that has been forgotten, confused, and altered over the past 160+ years.

And that truely is tragic.

Daniel Moore has been a tricky character to research. And next time I’ll go into research lessons you can use to find your tricky, tricky ancestors.