Pearl Harbor dominated the US news on December 9, 1941.

Then came word of Japan’s attacks on Manila, mere hours after the Hawaii bombings.

America was at war.

But 36-year-old Myrtle Boudreau was in the dark.

Sitting in her Astoria, Oregon, home, surrounded by family and news of war, she had important, unanswered questions:

Was her husband in a war zone?

Was he, at that moment, being attacked?

Was Napoleon Boudreau even alive?

A costly war-time error

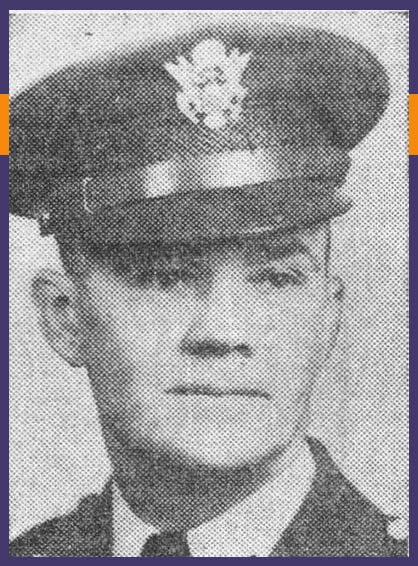

Colonel Napoleon Boudreau, Myrtle’s 53-year-old husband, was, in fact, in the middle of a war zone. But he was alive — and remained in command of Ft. Wint in The Philippines, not far from Manila.

Although that command wouldn’t last much longer.

War came to Ft. Frank a few days after Manila was attacked.

At 10:15 am on December 12, 1941, to be precise.

That’s when Japanese aircraft first strafed Ft. Wint. Aerial assaults and bombings continued daily for the next several weeks.

Miraculously, though, the fort suffered few casualties. American forces fared worse — much worse — elsewhere. As Christmas 1941 approached, American forces prepared to retreat to Bataan Peninsula.

And that’s when Col. Boudreau received the order — dismantle all stationary guns/artillery and evacuate the fort.

So, on Christmas Day 1941, Col. Boudreau, 33 officers, and 505 men evacuated the island fort and headed for Bataan.

It was a mistake.

One that may have cost the Americans Bataan — or at least played a part in its early fall.

But here’s the strange part — no one seemed to know who made that costly mistake. And would that mistake mean Myrtle never saw her husband again?

Love and loss

Years earlier as a young soldier, Napoleon Boudreau had assisted in building Ft. Wint — the island fort he’d eventually command and evacuate.

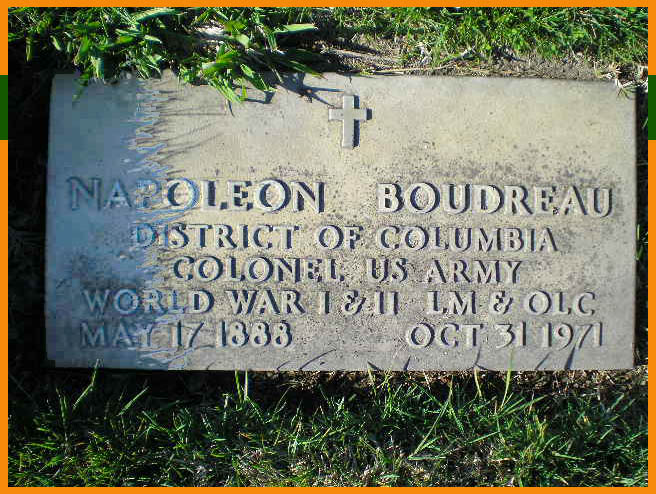

French Canadian by birth, Louis Napoleon Boudreau entered the world May 17, 1888, in the coastal village of Petit Rocher, New Brunswick. His parents, Philemon and Salome Boudreau, were farmers. Napoleon was their 6th child.

Napoleon Boudreau — a 5’9″ 20-year-old with blue eyes, light brown hair, and a ruddy complexion — came to the US in 1908, where he enlisted in the US Army. He rose up the Army ranks, eventually earning rank of Captain in November 1918.

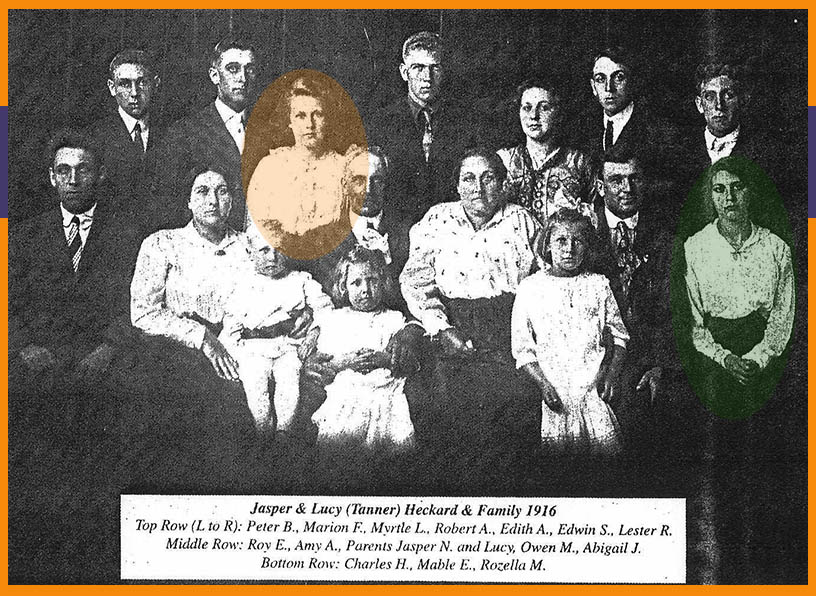

Although details of his early Army service are spotty, he was likely stationed in or near Astoria, Oregon, around 1914 — because he married 18-year-old Abigail Jane Heckard there on August 9, 1914.

Normand Napoleon Boudreau — Napoleon and Abigail’s son — was born on June 3, 1917. He died the same day. Then Abigail died about 5 weeks later, perhaps from child birth complications.

Napoleon never saw his son. And he was not with Abigail when she died. He may have already been in Europe, fighting WW1.

“In memory of my beloved wife into whose dying eyes, upon whose death-laid form I never gazed,” Napoleon inscribed on her grave stone, “and my child who I never saw, in the grave with its mother. My soul to God, my heart to you.”

I haven’t found specific details of his WWI service, but he returned to Astoria after the war — where he married Myrtle Heckard, Abigail’s 15-year-old sister, in January 1920. He was 33.

The peace years

By 1930, Napoleon and Myrtle lived in New York City. He may have worked as a professor of military tactics at Fordham University during this time period.

The couple then moved to Indianapolis, Indiana, in 1935, where Napoleon organized the state’s national guard.

In May 1940, Major Boudreau received a new, but very familiar, assignment — commander of Ft. Wint near Manila in The Philippines. He now commanded the fort he helped establish some 30 years previous.

Commanding Ft Wint

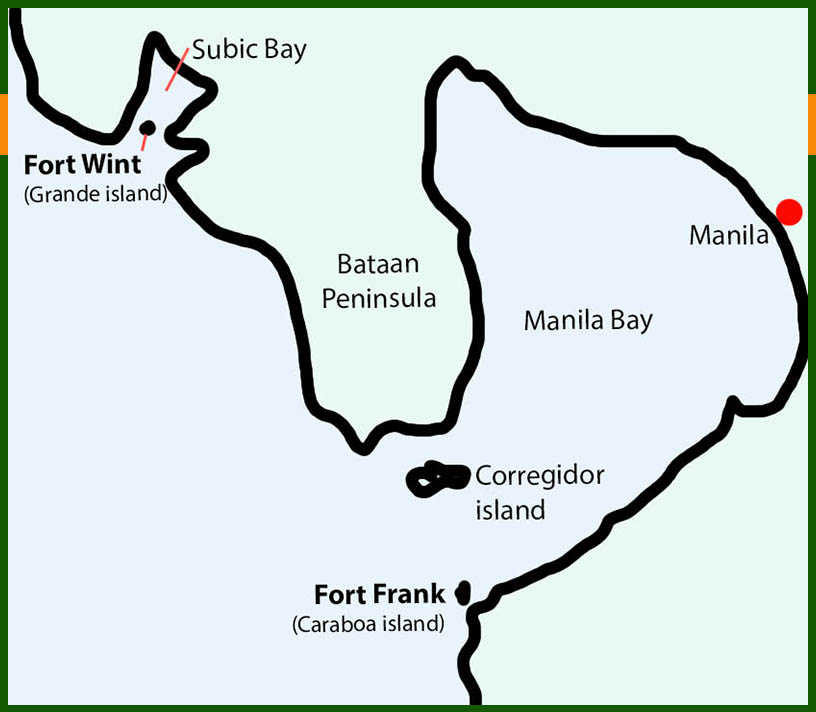

Ft. Wint sat on Grande Island in The Philippine’s Subic Bay. It protected Subic Bay’s entrance with heavy coastal artillery that could reach the Bataan Peninsula, making the island fort an important and strategic defense position.

During the years leading up to WW2, Ft Wint was a coastal artillery training ground.

American military in The Philippines knew that war with Japan was approaching, even before the first bombs dropped. By November 1941 — many weeks before the Pearl Harbor attack — Col. Boudreau oversaw daily coastal artillery and anti-aircraft practice sessions at Fort Wint.

The anticipated war soon arrived, and the November training sessions soon became December defensive maneuvers.

And then came that now-disputed Christmas Day evacuation.

Who ordered Ft. Wint’s evacuation?

The coastal artillery at Fort Wint could reach land targets on Bataan Peninsula. And that artillery could have slowed Japanese ground-troop progress down the peninsula, which fell to Japan in early April 1942 (3 months after Ft. Wint was evacuated).

After the war, no one seemed to know who ordered Ft. Wint’s evacuation.

At Christmastime 1941, US troops, units, ships, and all other military retreated to the southern Bataan Peninsula. Some historians suspect that someone at headquarters mistakenly assumed the Ft. Wint personnel should retreat too, since the fort was north of the Bataan retreat line.

And that was a strategic error.

Abandoning Ft. Wint handed the Japanese an important defense point. And it gave up heavy artillery that could have assisted the Bataan defense effort. It was an unfortunate blunder.

But, regardless of who ordered it, evacuate to Bataan they did. However Col. Boudreau wouldn’t find himself on the peninsula for long.

No, very soon he’d be in command of another island sentry.

Ft. Frank under seige

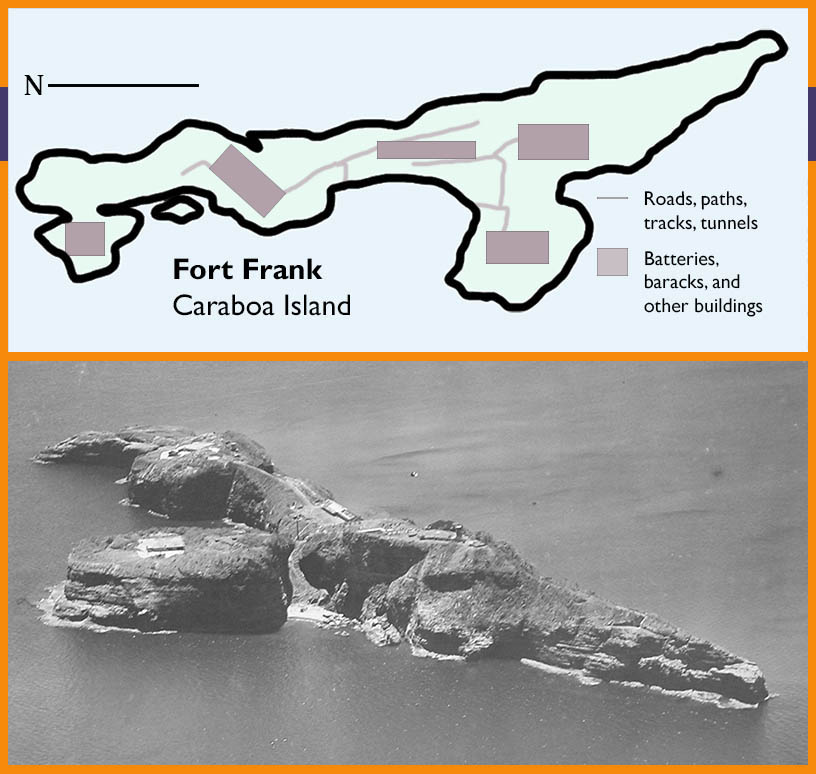

Sitting atop the sheer 100-foot cliffs of Caraboa Island, Fort Frank was one of 4 island fortresses guarding the entrance to Manila Harbor at the outbreak of WW2.

And by early January 1942, now-Colonel Boudreau commanded Fort Frank and it’s 400 American and Filipino military personnel.

Since the island was situated at the mouth of Manila Bay (see image 5 above), Fort Frank was mainly equipped with armor piercing artillery to attack incoming ships. Although it had some anti-aircraft weapons, the island fort remained quite vulnerable to air attack.

Luckily, much of the fort was underground and connected by tunnels, so the 4-month siege from January through May 1942 saw little loss of life.

Also, since it sat just .5 miles off The Philippine coast, the island was vulnerable to attacks from the Philippine mainland.

On February 16, 1942, Japanese demolition forces found and destroyed the pipeline that provided fresh water to the island fort from an onshore dam. Luckily the island’s salt-water distillery provided the fort’s personnel with water until the pipe was repaired a few weeks later.

Col. Boudreau surrenders

After Bataan peninsula fell in early April 1942, Japan turned their focus to the 4 island fortresses defending Manila Bay — the only remaining American strongholds in The Philippines. But American defenses wouldn’t last much longer. On May 6, 1942, Japanese troops invaded Corregidor — the largest of the defense islands — and America surrendered all of The Philippines to Japan.

Col. Boudreau oversaw destruction of Ft. Frank’s artillery and other weapons, so the Japanese could not use them.

Then Col. Boudreau surrendered Fort Frank to the Japanese. He was now a prisoner of war.

But, back in Oregon, Myrtle probably knew none of these happenings. If she received any war-time communications from her husband, we don’t know. It does seem, though, that she wouldn’t hear news of Napoleon for at least another year.

A year wondering, fretting, and not knowing whether her husband lived.

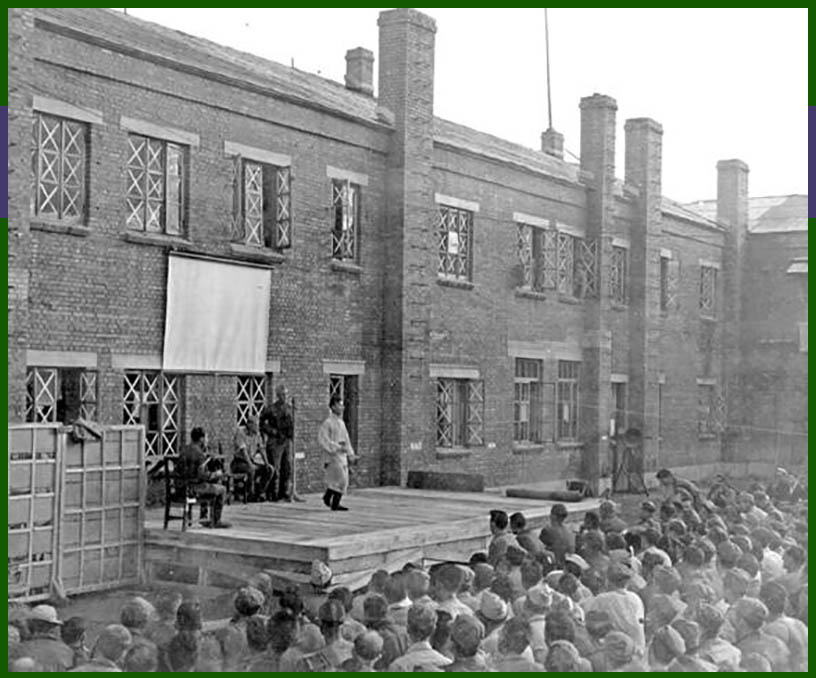

Commander of Cabanatuan POW camp

All POWs, regardless of rank, were alike to the Japanese. Therefore, Col. Boudreau was likely forced marched through Manila’s streets in late May 1942 in a show of Japan’s might over the American forces, then trained 70 miles to Cabanatuan City, and marched, again, 16 miles to Cabanatuan POW Camp #3.

Starting in late May 1942, “Colonel Napoleon,” as the Japanese called him, was the American camp commander at Cabanatuan POW Camp #3. He oversaw the organization and administration of the 2,000 Corregidor POWs and the Bataan Death March survivors in that camp.

When Col. Napoleon and his fellow POWs arrived, the camp was barren, with only empty barracks to house the POWs.

Col. Napoleon established an American camp government, and they created cooking protocol, sanitation infrastructure, medical facilities, and other ways to meet needs of POWs.

Basically, the Japanese made sure the POWs remained in the camp and performed various off-site work details — and issued punishments for “infractions.” The American camp command made sure the POWs had somewhat livable circumstances.

Boudreau was an “amiable commander” and a “fine understanding officer,” but his command of Camp #3 lasted only 3 months. In August 1942, Camp #3 closed and the POWs transferred to Cabanatuan Camp #1, about 10 miles away.

The Japanese had different plans for Colonel Napoleon, however, and “we were all sorry” to see him go, recalled POW Alma Salm..

The VIP prison camp in Taiwan

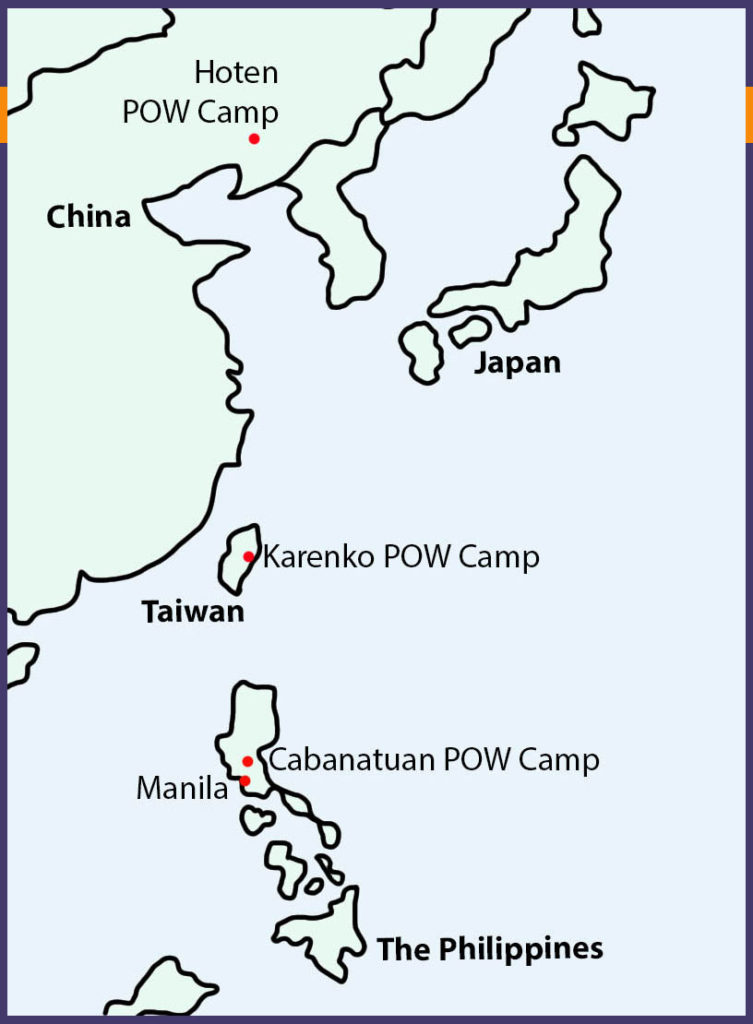

The Japanese sent Col. Boudreau to Karenko POW camp in Formosa (present-day Taiwan), after a brief stop over at Bilibid Prison in Manila.

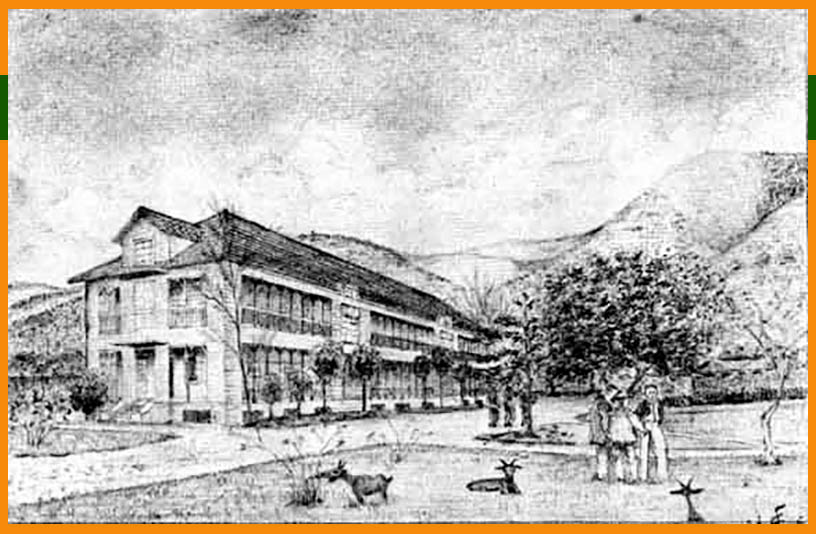

Karenko POW camp was an officers’ camp. Japan had a theory: separate allied high-ranking officer POWs from lower-ranking men, so the lower-ranking POWs would be easier for the Japanese to control. Karenko also imprisoned governors and other officials from countries that Japan had conquered.

As senior officers, the POWs were by and large older men. Col. Boudreau was 54 when he arrived. Lt. Gen. Wainwright, the highest-ranking American in The Philippines at surrender, was 59.

“The food was very bad,” reported one imprisoned officer, “and the treatment worse.” The Japanese humiliated, beat, and worked these older men hard at the camp’s farm (growing food that would be confiscated by the Japanese guards) and herding goats. Food and medical supplies were withheld.

Conditions were so bad that when the Red Cross requested to visit the Officer’s Camp, some 100 POWs were temporarily relocated to a different camp for the Red Cross visit. Of course, those men returned to Karenko after the visit.

Myrtle at a bomber factory

Back home, Napoleon’s wife Myrtle relocated to Seattle, where she worked in a bomber factory.

In summer 1943, a good year after his capture, Myrtle received news from the US War Department that her husband was a POW.

And in August 1943, she finally received a letter from him: “I am interred in Taiwan. My health is excellent. I am working in the garden for exercise. My love to you. Napoleon Boudreau, Feb. 20, 1943.”

The first 2 sentences were type written, probably a standard “letter” form created by the Japanese for all POWs to use.

The last two sentences and his signature were in his handwriting. His words would have been approved by Japanese before the letter was sent.

It took 6 months for the note to reach Myrtle. And, by that time, Karenko had closed and the POWs moved to another Taiwan POW camp.

The Manchurian camp

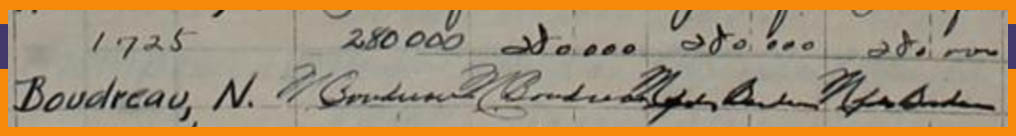

Around September 1944, a year after Myrtle received Napoleon’s letter, Col. Boudreau transferred to Hoten POW Camp, the largest Japanese camp in Manchuria (in present-day China, see image 9 above). The camp was in an industrial area near Mukden city.

Labor details at this camp were more intense than at the previous camp. POWs worked in a tannery, a textile factory, and a wood/steel mill. Although the POWs were paid for their work, the pay was minimal — around $.20 per month — for the back-breaking labor.

On August 6 and 9, 1945, the US dropped atomic bombs on Japan. The Russian Red Army soon invaded Manchuria and arrived at Hoten camp on August 19, 1945. US POW recovery teams also arrived, and the Russians and US worked together to evacuate the camp’s 1,300+ POWs.

This time, Myrtle Boudreau received almost immediate news of her husband — knowing of his release even before he left the camp.

Some VIPs and very sick POWs evacuated by air. Most however, likely including Col. Boudreau, left Hoten by train on September 11 and 12. They then boarded Navy ships for Okinawa. En route they were deloused, got new clothes, and received medical and dental treatment. From Okinawa, the POWs sailed for America.

After 40 months as a POW and more than 5 years away from home, Colonel Napoleon was a free man in the United States.

Napoleon comes home

Myrtle Boudreau lived in San Leandro, California, when Napoleon returned from war.

I wish I could tell you they lived happily ever after, but . . . their reunion didn’t last very long.

In January 1947, only 15 months after returning home, 59-year-old Napoleon married 31-year-old Kathryn Shamlain in San Francisco. Try as I might, I haven’t found what happened to Myrtle. Perhaps she died shortly after Napoleon’s return. Perhaps the couple divorced.

Col. Boudreau retired from the US Army in 1948 after 40 years of service.

Kathryn and Napoleon adopted an infant daughter in the late 1950s and lived in Santa Rosa, California, throughout the 1960s.

83-year-old Napoleon Boudreau died on October 31, 1971, in Santa Rosa. He rests in the Santa Rosa Memorial Park.

Read Next

Sources

- Abigail Jane Heckard Boudreau memorial, Find A Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/39020245/abigail-jane-boudreau, accessed 7 July 2020.

- Alma Salm, “A Brutally Honest Look Inside Japan’s Largest WW2 POW Camp,” Luzon Holiday, unpublished manuscript, in possession of Anastasia Harman, online at https://www.anastasiaharman.com/2020/05/02/cabanatuan-3-intro/.

- “Army Orders,” Seattle Daily Times, Seattle, Washington, 6 Nov 1918, page 11, found online at GenealogyBank.com, accessed 7 July 2020.

- “Card from Mate Held by Japs Reassures Wife,” Indianapolis Star, Indianapolis, Indiana, 24 August 1943, page 12, found online at NEwspapers.com, accessed 7 July 2020.

- Charles Bogart, “Subic Bay and Fort Wint – The Keys to Manila”, Corregidor Historical Society, found online at https://corregidor.org/chs_bogart/bogart1b.htm, accessed 8 July 2020.

- “Col Boudreau of City is Released from Jap Camp,” Indianapolis Star, Indianapolis, Indiana, 29 August 1945, page 3, found online at Newspapers.com, accessed 7 July 2020.

- Duncan Anderson, “Douglas MacArthur and the Fall of The Philippines,” in MacArthur and the American Century: A Reader, ed. William M. Leary (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), page 100, found online at https://books.google.com/books?id=xWv_2PwBXgMC&pg=PA100&lpg=PA100&dq=Napoleon+Boudreau&source=bl&ots=ZiMamZwljU&sig=ACfU3U1_SZP99fYElaxzAZZJIszrSl9mEQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiNhrTA-b3qAhWDIDQIHYh3BwoQ6AEwB3oECAsQAQ#v=onepage&q=Napoleon%20Boudreau&f=false, accessed 8 July 2020.

- “Fort Frank,” Wikipedia, found online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fort_Frank, accessed 8 July 2020.

- “Fort Wint,” Wikipedia, found online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fort_Wint, accessed 8 July 2020.

- “Hoten Camp–Mukden Manchuria, Bataan Project, found online at https://bataanproject.com/hoten-camp-mukden-manchuria/, accessed 9 July 2020.

- Marie Budrow in Jasper M Heckard family, Chadwell, Clatsop, Oregon; Roll: T625_1492; Page: 4A; Enumeration District: 70, Ancestry.com. 1920 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. (NARA microfilm publication T625, 2076 rolls). Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

- “KARENKO CAMP,” Taiwan POW Camps Memorial Society, Never Forgotten: The Story of Taiwan POW Camps and the Men Who Were Interred in Them,” found online at http://www.powtaiwan.org/The%20Camps/camps_detail.php?Karenko-POW-Camp-3&name=Karenko, accessed 9 July 2020.

- Louis Napoleon Boudreau. Ancestry.com. Acadia, Canada, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1757-1946 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2007. Original data: Gabriel Drouin, comp. Drouin Collection. Montreal, Quebec, Canada: Institut Généalogique Drouin.

- Napoleon Boudreau entry. Fort Wint, Grande Island, Philippines, Military and Naval Forces; Roll: T624_1784; Page: 1B; Enumeration District: 0144; FHL microfilm: 1375797. Ancestry.com. 1910 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2006. Original data: Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910 (NARA microfilm publication T624, 1,178 rolls). Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

- Napoleon Boudreau entry, Ancestry.com. California, Death Index, 1940-1997 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2000. Original data: State of California. California Death Index, 1940-1997. Sacramento, CA, USA: State of California Department of Health Services, Center for Health Statistics.

- Napoleon Boudreau, Ancestry.com. U.S. Army, Register of Enlistments, 1798-1914 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007. Original data: Register of Enlistments in the U.S. Army, 1798-1914; (National Archives Microfilm Publication M233, 81 rolls); Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1780’s-1917, Record Group 94; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

- Napoleon Boudreau, 1936, Indianapolis, Indiana, City Directory, Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

- Napoleon Boudreau, 1964 and 1965, Santa Rosa, California, City Directories, Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

- Napoleon Boudreau, Ancestry.com. U.S., Department of Veterans Affairs BIRLS Death File, 1850-2010 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011. Original data: Beneficiary Identification Records Locator Subsystem (BIRLS) Death File. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

- Napoleon Boudreau, Ancestry.com. U.S., Select Military Registers, 1862-1985 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2013. Original data: United States Military Registers, 1902–1985. Salem, Oregon: Oregon State Library.

- Napoleon Boudreau, Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935-2014 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2014. Original data: Social Security Administration. Social Security Death Index, Master File. Social Security Administration.

- Napoleon Boudreau, Ancestry.com. World War II Prisoners of the Japanese, 1941-1945 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com operations, Inc., 2010.

- Napoleon Boudreau, Ancestry.com. World War II Prisoners of War, 1941-1946 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2005. Original data: National Archives and Records Administration. World War II Prisoners of War Data File [Archival Database]; Records of World War II Prisoners of War, 1942-1947; Records of the Office of the Provost Marshal General, Record Group 389; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

- Napoleon Boudreau family, Bronx, Bronx, New York; Page: 3A; Enumeration District: 0601; FHL microfilm: 2341221. Ancestry.com. 1930 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2002. Original data: United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1930. T626, 2,667 rolls.

- Napoleon Boudreau memorial, Find A Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/125509722, accessed 14 July 2020.

- Napoleon Boudreau obituary, The Press Democrat; Publication Date: 3/ Nov/ 1971; Publication Place: Santa Rosa, California, United States of America, found online at Newspapers.com, accessed 7 July 2020.

- Napoleon Boudreau and Abigail Jane Heckard entry, Ancestry.com. Oregon, County Marriage Records, 1851-1975 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2016. Original data: Marriage Records. Oregon Marriages. Various County Courthouses, Oregon.

- Napoleon Boudreau and Myrtle Neckard entry, Ancestry.com. Oregon, County Marriage Records, 1851-1975 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2016. Original data: Marriage Records. Oregon Marriages. Various County Courthouses, Oregon.

- Normand Napoleon Bourdreau memorial, Find A Grave, found online https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/39020252/normand-napoleon-boudreau, accessed 7 July 2020.

- “May Be in War Zone,” Indianapolis News, Indianapolis, Indiana, 9 December 1941, page 10, found online at Newspapers.com, accessed 7 July 2020.

- Philemon Boudreau family. Beresford (Parish/Paroisse), Gloucester, New Brunswick; Page: 4; Family No: 25. Ancestry.com. 1901 Census of Canada [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2006. Original data: Library and Archives Canada. Census of Canada, 1901. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Library and Archives Canada, 2004. http://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/census/1901/Pages/about-census.aspxl. Series RG31-C-1. Statistics Canada Fonds. Microfilm reels: T-6428 to T-6556. Images are reproduced with the permission of Library and Archives Canada.

- Philomen Boudreau family, Beresford, Gloucester, New Brunswick, Canada; Roll: T-6299; Family No: 144. Ancestry.com. 1891 Census of Canada [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2008. Original data: Library and Archives Canada. Census of Canada, 1891. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Library and Archives Canada, 2009. http://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/census/1891/Pages/about-census.aspx. Series RG31-C-1. Statistics Canada Fonds. Microfilm reels: T-6290 to T-6427.

- “The Siege of Corregidor,” Louis Morton, The War in the Pacific: The Fall of the Philippines, Washington, DC: Center of Military History, US Army, 1953, page 484-5, found online at https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/5-2/5-2_27.htm, accessed 8 July 2020.

Images

- Image 1. Napoleon and Myrtle. Uploaded by John Duresky, Napoleon Boudreau memorial, Find A Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/125509722, accessed 7 July 2020.

- Image 2. Portrait of Napoleon Boudreau. Uploaded by John Duresky, Napoleon Boudreau memorial, Find A Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/125509722, accessed 7 July 2020.

- Image 3. Heckard family. Jasper Newton Heckard Family, uploaded to Ancestry.com family tree by Judith Heckard, 07 Aug 2016, found online at https://www.ancestry.com/mediaui-viewer/collection/1030/tree/168661334/person/262205439206/media/802c1179-41df-4c25-b303-721de1595cd8?_phsrc=gPb4038&usePUBJs=true, accessed 7 July 2020.

- Image 4. Graves for Abigail and Normand. Abigail grave inscription: Uploaded by Kara, Abigail Jane Heckard Boudreau memorial, Find A Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/39020245/abigail-jane-boudreau, accessed 7 July 2020. Norman grave: Uploaded by Kara, Normand Napoleon Boudreau memorial, Find A Grave, found online https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/39020252/normand-napoleon-boudreau, accessed 7 July 2020.

- Image 5. Map of Subic and Manila Bays. Create by Anastasia Harman, July 2020.

- Image 6. Ft. Wint ca 1932. National Archive and Records Administration Image, public domain, found online at https://www.flickr.com/photos/44567569@N00/21932810795/in/album-72157658661455655/, accessed 8 July 2020.

- Image 7. Ft Frank map and pic. Ft Frank Map: Map created by Anastasia Harman, June 2020. Aerial view of Caraboa Island: National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) image, found online at https://www.flickr.com/photos/44567569@N00/30380121831/in/album-72157673964028162/, accessed 12 June 2020.

- Image 8. Cabanatuan image: Created 1943, Public domain image, Courtesy of the MacArthur Memorial Library, Norfolk, Virginia, found online at https://www.dvidshub.net/image/3587783/cabanatuan-prisoner-war-camp, accessed 14 July 2020.

- Image 9. POW Camp map: Created by Anastasia Harman, July 2020.

- Image 10. Karenko drawing. Major General H.J.D. de Fremery, found online at http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/china_hk/karenko.html, accessed 9 July 2020.

- Image 11. Hoten Camp Photo. National Archives photo. found online at https://www.military.com/history/jd-osborne-veteran-story.html, accessed 9 July 2020.

- Image 12. Hoten Payroll record. POW payrolls and deposits HOTEN, National Archives and Records Administration RG 331, Box 3959, image 39, found online at http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/china_hk/mukden/POW_payrolls_deposits_HOTEN_RG331Bx3959.pdf, accessed 9 July 2020.

- Image 13. Napoleon Boudreau grave. Uploaded by Jim C, Napoleon Boudreau memorial, Find A Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/125509722, accessed 7 July 2020.

Good evening – I have some input for you concerning what you have written about my father, Col. Napoleon Boudreau, but your site does not provide contact information for *private* communication. Please contact me. Thank you in advance for your reply.