If Machinist Hutchison heard the approaching aircraft, he probably didn’t take notice.

Bombing runs had become commonplace over the last several weeks, as Japanese swiftly and strategically overran Luzon island in The Philippines.

And, besides, the Machinist had other responsibilities on his mind. Like overseeing the USS Canopus’s Engine Room, which he was commanding in the late afternoon on December 29, 1941.

Regardless of what he did or did not hear, he definitely felt the repercussions of those aircraft.

An armor-piercing bomb tore through the Engine Room, breaking pipes which sprayed scalding steam, oil, and other throughout the close quarters.

He was injured immediately. Incapacitated. Badly wounded.

Ship bombings would become a theme of Machinist Hutchison’s WW2 experience.

He had survived this first one. Could he survive a second?

Early Life

William Adolphus Hutchison spent his childhood on his family’s farm in rural Indian Valley, Idaho (about 90 miles north of Boise). He was the second of 8 children born to William and Viola Hutchison. Father William owned and worked his farm in Idaho.

Around 1919, the Hutchison family moved just minutes south of the Canadian border to a farm near Bellingham in western Washington state. Adolphus, as he seems to have been called, was about 11 years old.

He spent his teen years in the Bellingham area, although we have few specific details about his life in Washington.

He likely joined the Navy in the early-to-mid-1930s, because in July 1938, he became a Machinist (an enlisted naval rating).

By 1941, he was a Warrant Machinist aboard the USS Canopus. That made him a Warrant Officer, which, from what I understand about US Navy ranks, is similar to the Army’s non-commissioned officers — like corporal or sergeant.

In other words, Adolphus had worked his way up the Navy ranks from enlisted to an warrant officer.

Attack on the USS Canopus

That’s why, late in the afternoon of December 29, 1941, just a few weeks after the Pearl Harbor attack, Machinist Hutchison was in the USS Canopus‘s Engine Room with Electrician Alton Hall (another warrant officer) and several crew members.

Corrigidor island, just a few miles away, was being bombed non-stop by Japanese aircraft. So approaching enemy aircraft had become commonplace.

But this time, Corregidor wasn’t the pilots’ target. The Canopus, anchored in Mariveles harbor, was.

Surprisingly only one of the many bombs dropped on the Canopus actually struck the ship. But it was an armor-piercing bomb that went through all the ship’s decks — including the Engine Room.

Metal fragments and boiling-hot steam from broken pipes filled the room, badly injuring Hutchison and Hall and killing several crew members.

The ship’s Machinists Mate, taking charge for the incapacitated Hutchison and Hall, shut off the steam at the boilers. His quick actions saved more men from being being scalded to death.

Rescued by the “fighting chaplain”

Soon the ship’s “fighting Chaplain” (religious leader) arrived with an impromptu rescue party. They evacuated Hutchison, Hall, and other injured sailors to first-aid areas.

But conditions outside the Engine Room weren’t much better.

After tearing through the Engine Room and other decks, the bomb exploded near the ship’s magazine (place where ammunition is held). The explosion started several fires, which threatened to ignite the ammunition.

So above deck, the Engine Room survivors found a chaotic scene of men trying to put out fires with hoses and even bucket brigades. Below deck, others groped through smoke-filled corridors to help fellow sailors escape.

When the smoke had, literally, cleared, the Canopus was still standing…or floating, as the case may be.

Capture and POW Life

I’m not 100% sure where an injured Adolphus Hutchison recovered.

My best guess is that he was taken to the military hospital on Corregidor Island, just a couple miles across Manila Harbor from where the Canopus was anchored. The hospital, located inside Malinta Hill, would have offered medical treatment and safety from the constant bombardment.

Regardless of where he actually recovered, Hutchison ended up on Corregidor island at least by early April 1942.

The Japanese had successfully taken most of The Philippines, and the island-military base of Corregidor was one of the last American and Filipino resistance points. The Japanese laid siege to the island for the next month, including a blockade the prevented US ships and supplies to get to the island.

Hutchison, likely still recovering from his wounds, endured weeks of hunger, sickness, and Japanese bombings — until the Japanese conquered Corregidor on May 6, 1942, and Machinist Hutchison became a prisoner of war.

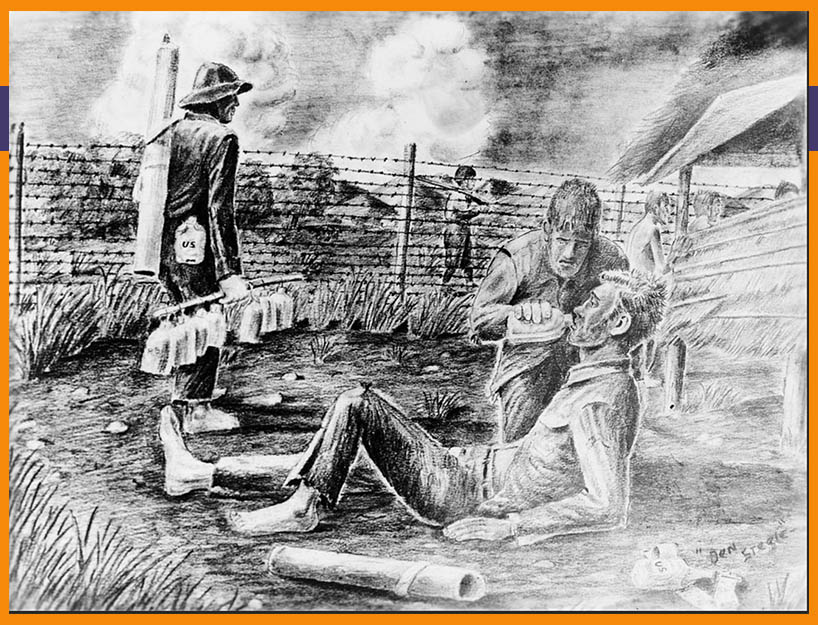

With the other American POWs captured on Corregidor, Hutchison was force marched through Manila and eventually to Cabanatuan prison camp (70 miles north of Manila).

Life in Cabantuan POW camp was hard. The POWs were starved. They were sick. They were beaten and tortured. They slowly wasted away while forced into backbreaking work.

For nearly 2.5 years, Hutchison endured this inhumane treatment.

And then, well, something changed.

Packed aboard a hell ship

The Americans returned.

By October 1944, US and other Allied forces made significant advancements toward Manila. Allied air raids on The Philippines increased. And Japanese leaders began moving POWs to work camps in Japan.

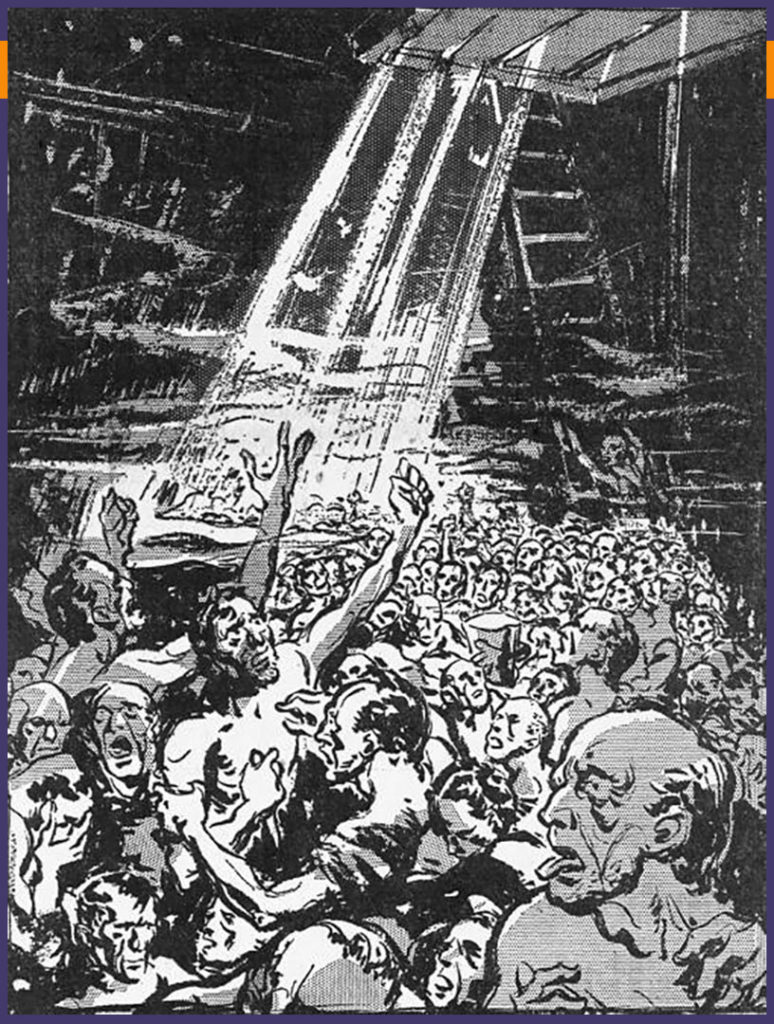

So, on October 11, 1944, 36-year-old Adolphus Hutchison and 1,782 other POWs were quickly loaded, between air raids, in to a cargo hold of Japanese transport ship Arisan Maru at a Manila dock.

Hutchison and the other sick, starving, and emaciated men, having already endured the torture of Japanese POW camps for 29 months, were now packed in to a ship hold.

Even though each POW had eight 5-gallon oil barrels for waste, rampant dysentery quickly made for extremely unsanitary conditions. The hold’s temperatures reached upwards of 120 degrees Fahrenheit, and the men didn’t have enough water.

For these and other reasons, the Arisan Maru was a hell ship.

The ship headed out to sea for 9 days to avoid bombings in Manila, then returned to the city where it joined a convoy of 17 other Japanese ships — including 3 destroyers for protection. The convoy left left Manila in the early-morning darkness of October 21, heading for Takao (present-day Kaohsiung, Taiwan).

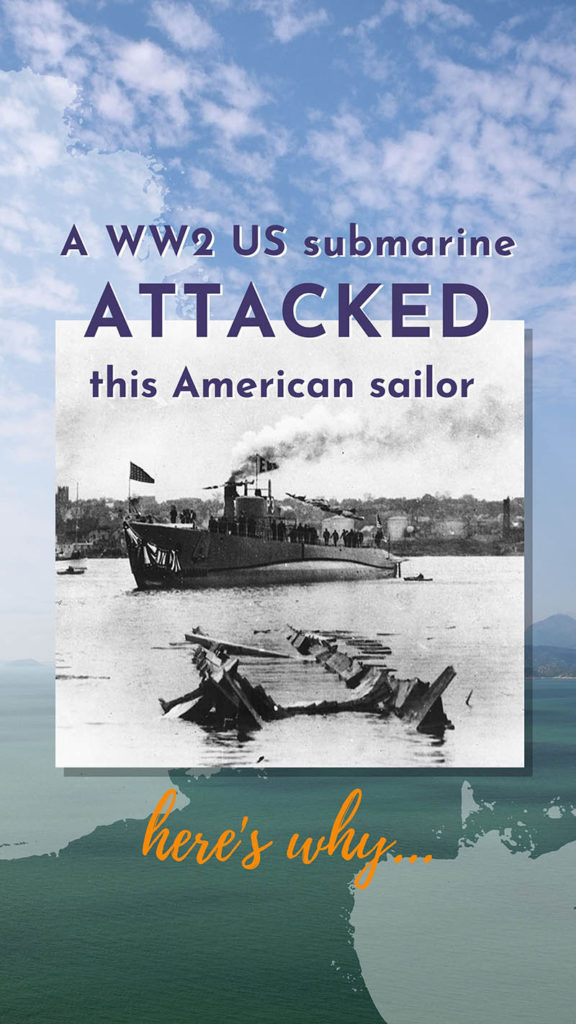

The Shark attack

Two days later, the Japanese destroyers picked up signals from American submarines. In response, the convoy broke apart.

The Arisan Maru was slow. The slowest of the convoy.

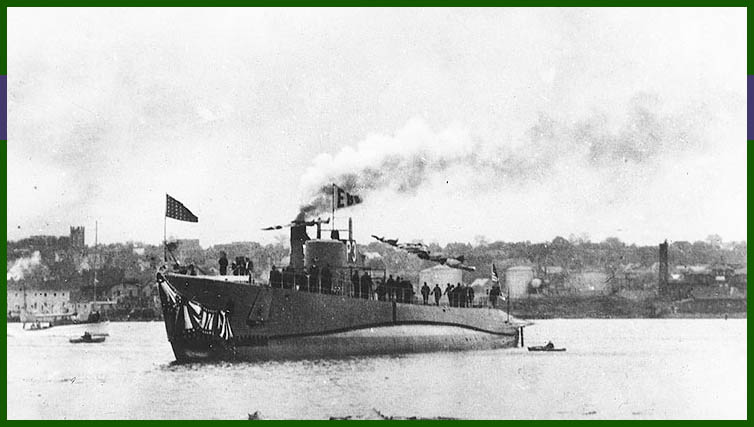

By 5 pm on October 24, 1944, the Arisan Maru was travelling alone when the American sub USS Shark launched a torpedo at it. The Japanese ship was unmarked; the Americans had no idea the cargo in it’s hold.

The ship split in half, the back sinking into the sea, but stayed afloat until around 7:40 pm. Nearly all the POWs escaped the ship, despite guards cutting the hold’s rope ladders as the Japanese abandoned ship. (Reports say that no POWs died when the torpedo hit the ship.)

Two Japanese destroyers returned to the scene. They attacked and sank the Shark (all 87 American sailors on that sub died). The destroyers then turned to rescuing survivors.

Japanese survivors.

POWs swam through the South China Sea waters to the destroyers. But they didn’t meet with rescue. Instead, those on board the destroyers used poles to push and beat away the frantic POWs.

Desperate POWs clung to whatever pieces of wreckage they could find. But help never arrived. Only 9 POWs survived, having found a lifeboat and padding to some type of safety.

Sadly, Adolphus was among the 1,773 military and civilian POWs who drowned (or worse), making the Arisan Maru sinking the largest loss of American lives in a single maritime incident.

Honoring Machinist Hutchison

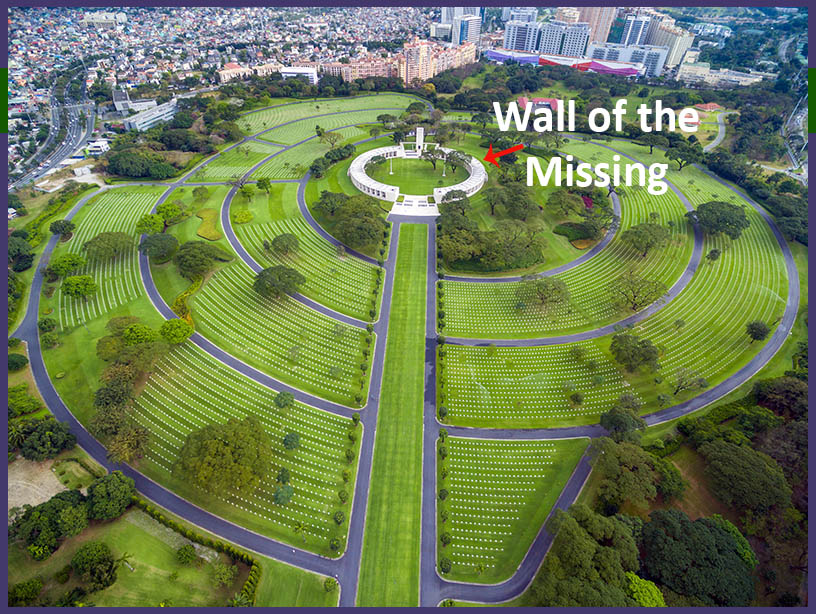

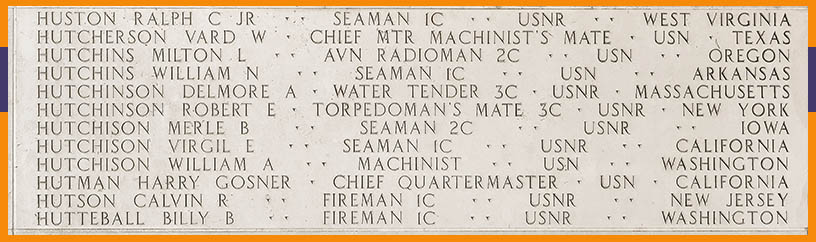

Machinist William Adolphus Hutchison’s name appears on the Wall of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery, along side 36,285 other WW2 servicemen whose bodies were unrecoverable (many died in ship sinkings).

Sometime before WW2, Adolphus married a woman named Thelma. Other than her name listed as his wife and next-of-kin on a casualty report, I’ve found nothing about her. I don’t know if they had children together.

All 3 of Adolphus’s brothers –Truman, Tom, and Asa Hutchison — served in the US Navy during WW2. However, unlike Adolphus, they all returned home from the war.

My go-to picture-finding places

Finding a picture of each POW is one of my main research goals. It’s a task I’ll spend A LOT of time on, if needed. Sadly, though I haven’t yet found a picture of Adolphus Hutchison.

Since finding photos is a question I get asked quite a bit, here’s a run down of my go-to picture-finding resources. You can use all of them to find pics of your people (even if they weren’t WW2 servicemen or women):

- US Yearbook Collection on Ancestry.com — A collections of thousands of yearbooks from elementary schools, high schools, colleges, and more spanning from 1900-1999.

- Trees on Ancestry.com and FamilySearch — People have uploaded millions family member pictures to their trees on Ancestry.com and on FamilySearch. Be cautious, though, because some pictures may be misidentified

- Individual Memorials on Find A Grave — Find A Grave is a crowd-sourced collection of grave markers from cemeteries all over the world. Sometimes people attach other photos as well as a grave marker photo. The info is provided by volunteers and is 100% free to use. As with any crowd-sourced info, some pics may be misidentified.

- Obituaries on Newspaper.com and GenealogyBank.com — Obituaries often include photos of the people who have passed. These two subscription websites are my go-to sources for newspaper articles and obituaries. Ancestry.com also has newspapers, but the collection isn’t huge.

- Local Libraries — Sadly, not everything is online. So when my picture-finding resources fail me, I search the Google for the local library where the person I’m researching lived around the time he/she died. Many libraries have archive copies of local newspapers. And some libraries will even do a search for you!

This last bullet brings me to my next point…

A big thank you to Diane Formway, a Public Services Librarian, at Bellingham Public Library in Bellingham, Washington.

When I couldn’t find a pic online, I called the Bellingham Public Library and told them about Adolphus. Diane then spent quite a bit of time looking through archives of local newspapers and other sources from the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s to see if there was an obit, a news story, or any further information about Adolphus. Again, nothing.

I am so grateful for Diane’s help with this search! And this is something you can try for your own family. Not every library offers these services — but it’s worth a Google and a phone call to find out!

Read Next

Sources

- Adolphus Hutchison entry, U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995, database online, Ancestry.com, original data: Bellingham, Washington, City Directory, 1926, accessed 4 March 2020.

- “Arisan Maru,” Wikipedia, found online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arisan_Maru, accessed 25 February 2020.

- Asa Isic Hutchison, 1 October 1945 muster roll for ship number APA-73, U.S. World War II Navy Muster Rolls, 1938-1949, database on-line, Ancestry.com, original data: Muster Rolls of U.S. Navy Ships, Stations, and Other Naval Activities, 01/01/1939-01/01/1949; A-1 Entry 135, 10230 rolls, ARC ID: 594996, Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, Record Group Number 24, National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD, accessed 13 March 2020.

- “Captain Sackett’s History of the Original USS Canopus,” Chapter 3, Larry’s Home Port, found online at http://as9.larryshomeport.com/html/chapter_iii.html, accessed 11 March 2020.

- “‘H’ Section,” Bill Bowen’s Arisan Maru Roster, found online at https://www.west-point.org/family/japanese-pow/ArisanFiles-2/H.htm, accessed 25 February 2020.

- “Hell Ship Information and Photographs,” found online at https://www.west-point.org/family/japanese-pow/photos.htm, accessed 13 February 2020.

- Mach William A Hutchison memorial, Find A Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/56783213, accessed 3 March 2020.

- Thomas Hutchison entry, U.S., Department of Veterans Affairs BIRLS Death File, 1850-2010, database online, Ancestry.com, original data: Beneficiary Identification Records Locator Subsystem (BIRLS) Death File, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, accessed 13 March 2020.

- Truman Richard Hutchison, 31 Aug 1944 muster roll for ship number YMS-127, U.S. World War II Navy Muster Rolls, 1938-1949, database on-line, Ancestry.com, original data: Muster Rolls of U.S. Navy Ships, Stations, and Other Naval Activities, 01/01/1939-01/01/1949; A-1 Entry 135, 10230 rolls, ARC ID: 594996, Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, Record Group Number 24, National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD, accessed 13 March 2020.

- William Bowen, “The Arisan Maru Tragedy,” US-Japan Dialogue on POWs, found online at http://www.us-japandialogueonpows.org/Bowen.htm, accessed 25 February 2020.

- William Hutchison family, 1920 United States Federal Census, database online, Ancestry.com, images reproduced by FamilySearch, original data: Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920, NARA microfilm publication T625, 2076 rolls, Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29, National Archives, Washington, D.C., accessed 3 March 2020.

- William Adolphus Hutchison entry, Idaho, Birth Index, 1861-1917, Stillbirth Index, 1905-1967, database online, Ancestry.com, original data: Idaho Department of Health and Welfare, State Birth Index, Idaho Bureau of Vital Records and Health Statistics, Boise, Idaho, accessed 3 March 2020.

- William Adolphus Hutchison, U.S., Select Military Registers, 1862-1985, database online, Ancestry.com, original data: United States Military Registers, 1902–1985, Salem, Oregon: Oregon State Library, accessed 3 March 2020.

- William M Hutchison family,1910 United States Federal Census, database online, Ancestry.com, original data: Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910, NARA microfilm publication T624, 1,178 rolls, Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29, National Archives, Washington, D.C, accessed 5 March 2020.

- Wm A Hutchison entry, World War II Prisoners of War, 1941-1946, database online, Ancestry.com, original data: National Archives and Records Administration, World War II Prisoners of War Data File [Archival Database]; Records of World War II Prisoners of War, 1942-1947; Records of the Office of the Provost Marshal General, Record Group 389; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD, accessed 3 March 2020.

Images

- Image 1: Bellingham, Washington. Licensed from Adobe Stock Photos.

- Image 2: USS Canopus. Official US Navy image, image number 80-G-1014615, in the collections of the US National Archives and Records Administration, found online at Naval History and Heritage Command, Department of the Navy, https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/OnlineLibrary/photos/sh-usn/usnsh-c/as9.htm, accessed 19 August 2019.

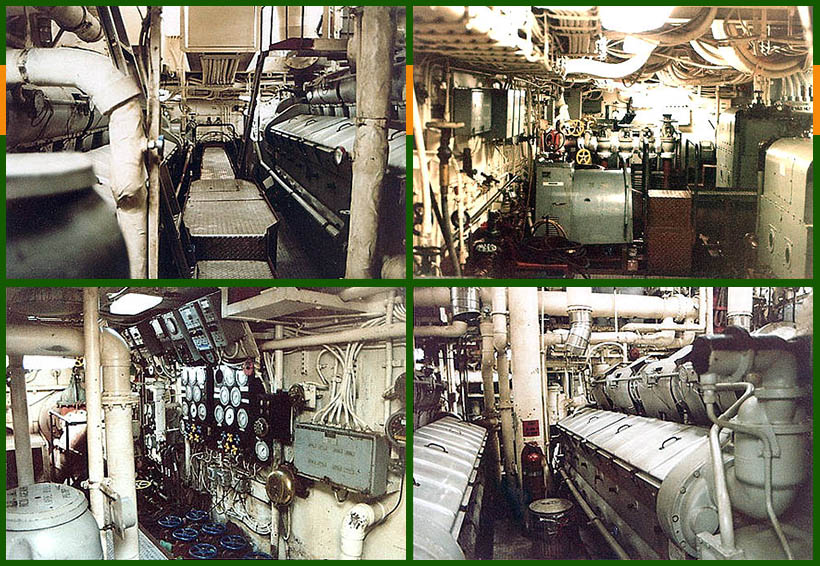

- Image 3: Proteus engine room. “USS Proteus AS 19 Page 2,” Submarine Tenders, Tender Tale United States Navy, found online at http://www.tendertale.com/tenders/119/119-2.html , accessed 13 March 2020.

- Image 4: Malinta Tunnel hospital. Found online at John Moffitt, “The Malinta Tunnel, from Concept to Completion,” Dec 2012, Rediscovering Corregidor, http://corregidor.org/fieldnotes/htm/fots2-121224-2.htm, accessed 6 August 2019.

- Image 5: Drawing of Cabanatuan. By former POW Ben Steele.

- Image 6: Arisan Maru image. “Hell Ship Information and Photographs,” found online at https://www.west-point.org/family/japanese-pow/photos.htm, accessed 13 February 2020.

- Image 7: Drawing of POWs on hell ship. From George Weller, “Death Cruise, Part 2: Yanks Go Mad on Agony Ship,” Chicago Daily News, November 9, 1945, found online at “News from the Past,” POW Resources, http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/newspaper/newsfrompast-cruiseofdeath.html, accessed 13 August 2019.

- Image 8: USS Shark. USS Shark (SS-174) immediately after launching by the Electric Boat Company, Groton, Connecticut, 21 May 1935. U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph, photo #NH 42075, public domain, found online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Shark_(SS-174)#/media/File:USS_Shark_SS-174_H42075.jpg, accessed 25 February 2020.

- Image 9: Map of Arisan Maru sinking. Created by Anastasia Harman.

- Image 10: Manila American Cemetery. Adobe Stock Photo. Licensed by Anastasia Harman.

- Image 11: Hutchison Memorial Marker. “William A. Hutchison,” American Battle Monuments Commission, found online at https://www.abmc.gov/node/466566, accessed 25 February 2020.