An air raid alert sounded at the Sakura Military Hospital in Manila, Philippines.

It was 5:30 am. Sunday, November 19, 1944.

The hospital’s Japanese guards ran, in full gear, for their fox holes. The Americans — some medical personnel, some patients, all prisoners of war — were ordered inside the hospital.

Planes arrived from all directions. Their markings were clear: American planes. The Yanks were coming. And that bolstered hope. Because, even though the American prisoners were starving and sick, somehow these “Yank visits” (air raids) were “a treat for starvation.”

But not every American was excited.

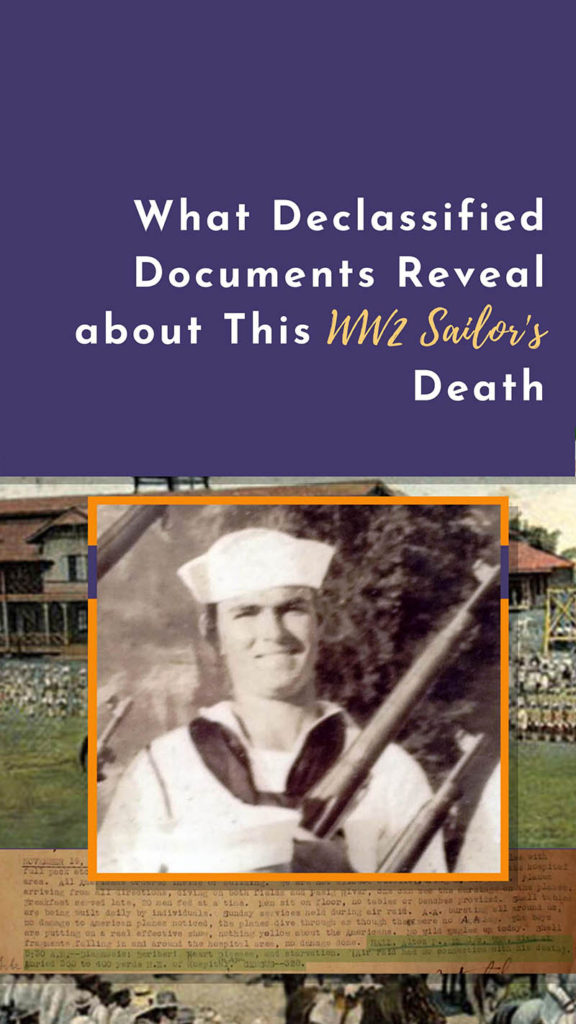

No, in a quiet, dark corner, covered by mosquito nets in the fly-infested hospital lay 30-year-old sailor Alton Henry Hall.

Texas farm boy to Navy electrician

Alton was a Texas farm boy, born and raised near a rural town called Comanche. Born August 26, 1914, he was the second of 3 boys and one daughter born to Henry and Amanda Hall.

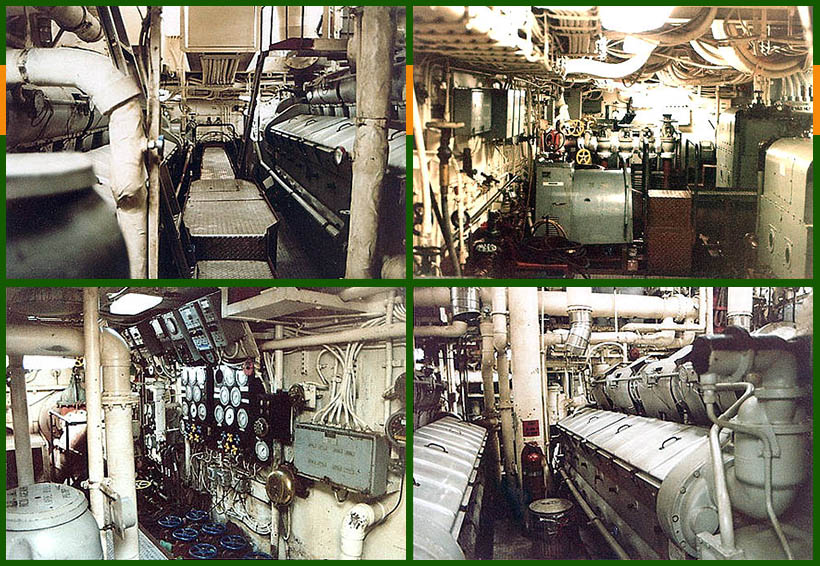

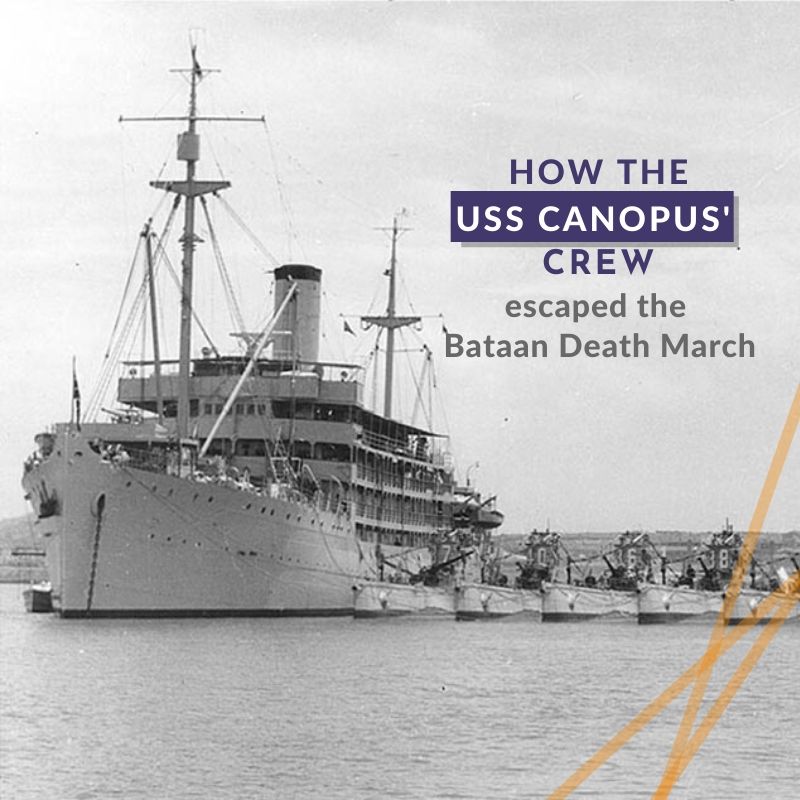

I know little of Alton’s early years. In November 1936, the grey-eyed, brown-haired 22-year-old enlisted in the Navy. By the end of 1941, when WW2 broke out in The Philippines, Alton was serving as an Electrician’s Mate on board the submarine tender USS Canopus.

Surviving a ship bombing

At first, the Canopus was not a target for the Japanese bombers. But as the bigger US Navy ships fell, the Japanese turned their sights to other American ships — like the Canopus.

In the late afternoon of December 29, 1941, Electrician Hall was in the ship’s Engine Room, along with Warrant Machinist Adolphus Hutchison and several other crew members, when an armor piercing bomb struck the Canopus.

It sliced through the Engine Room, filling the room with metal fragments and boiling-hot steam from broken pipes. Electrician Hall was badly burned, Hutchison injured, and several crew members killed.

Unable to flee on their own, Hall and other surviving crew were soon rescued and carried to make-shift aid stations.

Alton Hall becomes a prisoner of war

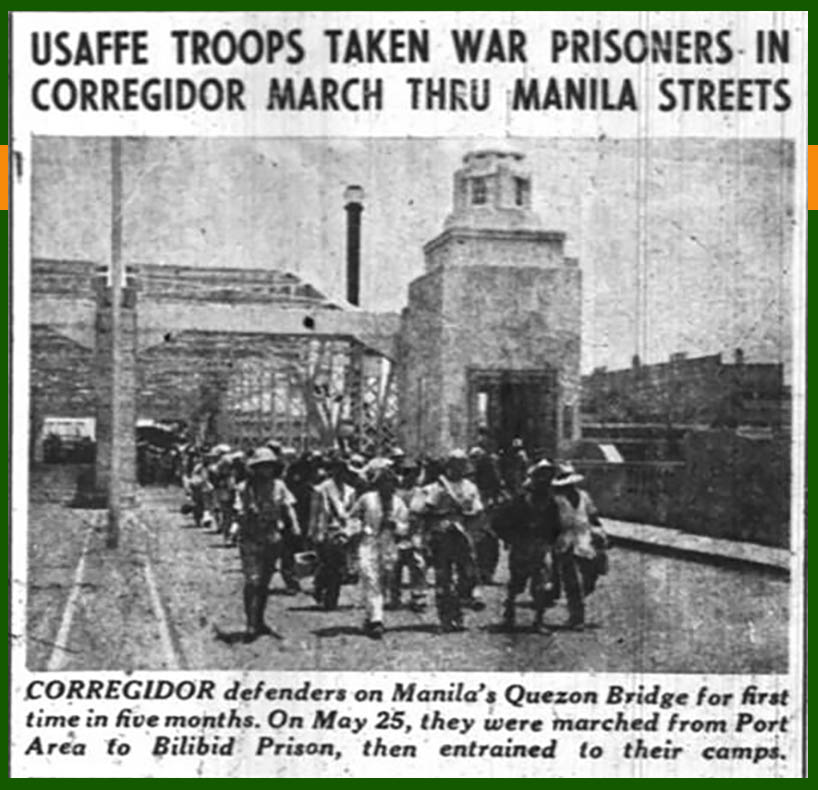

Alton Hall likely spent time in the military hospital inside the tunnel under Malinta Hill on Corregidor island. He had only 4 months to convalesce, as Japanese troops invaded Corregidor on May 6, 1942, capturing Hall and some 14,000 other American and Filipino fighters.

Although I haven’t found specific records of his experiences from May 1942 through fall 1944, he would have been part of the forced American march through Manila and on to Cabanatuan POW camp.

To say life as a POW was hard is a gross understatement. Alton and his fellow POWs were starved, disease ridden, beaten, worked nearly to death, and more. And if Alton were still recovering from his burns and wounds, his experience would have been that much more miserable.

Transfer to Sakura POW Hospital

By fall 1944, Electrician Hall was in a military hospital at Manila’s Bilibid Prison (a POW holding facility and hospital) suffering from beriberi and severe malnutrition.

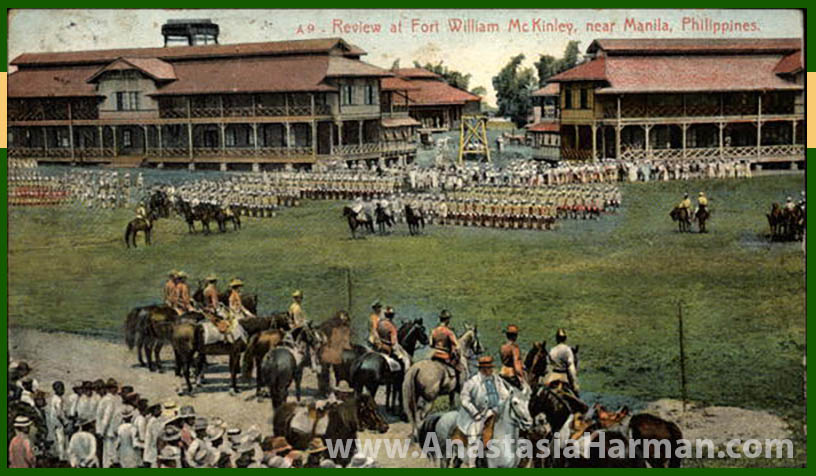

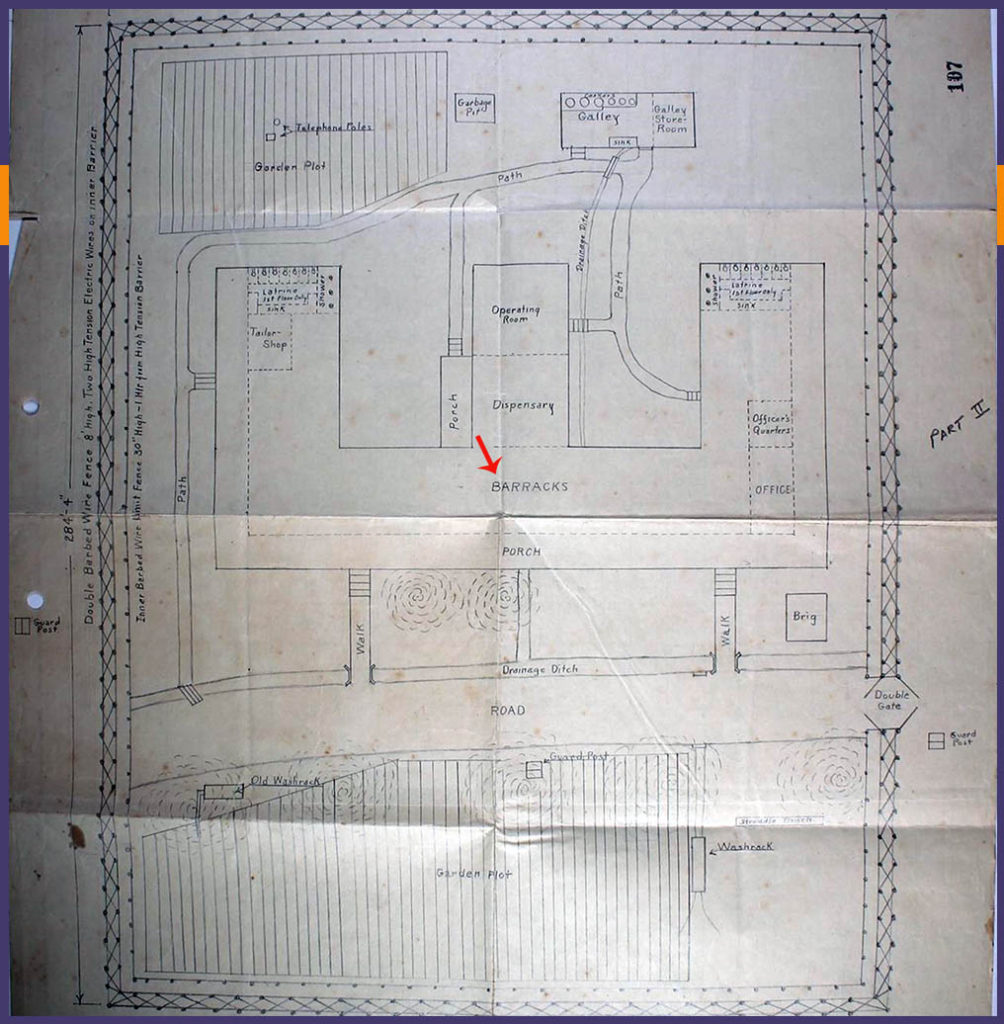

Seeking to ease Bilibid’s overcrowding issues, the Japanese established Sakura Prison Hospital, located in the former American base Ft. William McKinley in Manila. This hospital, staffed by American POW medical personnel, opened on November 15, 1944.

At 6 am on November 15, 1944, a very sick Alton Hall and 150 other Bilibid POW patients transferred to Sakrua.

After 2 years and 6 months as a POW, the 5’10” Alton weighed a mere 90 pounds.

The hospital was a 2-story building. A dirty, unfurnished, unsanitary 2-story building. No beds. No mattresses. Instead, the Japanese provided 1 nipa mat per four patients. Some men did not get blankets. The weak, sick, starving patients received corn and rice twice a day.

But, despite the hopelessness of their situation, there was optimism among the patients — American air attacks on Manila. The Americans were returning.

But even in that, there was risk. On November 17, the hospital’s American director requested permission to paint a large red cross on the building’s roof, so the American’s wouldn’t bomb the hospital filled with sick American POWs.

A grim discovery

So it was probably with a mix of joy and trepidation that the Sakura POWs watched American plane approaching at 5:30 am on Sunday, November 19, 1944. The American planes arrived from all directions, diving among the field and city of Manila. The raid continued through breakfast and even a Sunday service, with shells and fragments falling around the hospital grounds.

But Alton Hall was not among the patients at breakfast or watching the air raid or praying in the service.

No, he was lying on his nipa mat. And who knows when exactly, during all the tumult of the miring raid, it was discovered that Electrician Hall had died “during the night without calling for medical attention.” Officially, he passed sometime between 2 am and 5:30 am. Officially, he died of beriberi, heart disease, and severe malnutrition. Officially, the hardships of this unequipped, unprepared prison camp contributed to the death.

Alton Hall was buried about 400 yards from the Sakura camp. He was the first of two deaths during the 6 weeks this hospital/camp was open. The Americans finally arrived in Manila in January 1945, but that was mere weeks too late for Alton Hall.

Alton Hall returns home

Alton’s two brothers — Oliver and Orval Hall — served in WW2 as well. One in the Army, on in the Air Corps. Both of these brothers returned home from war, married, and had families.

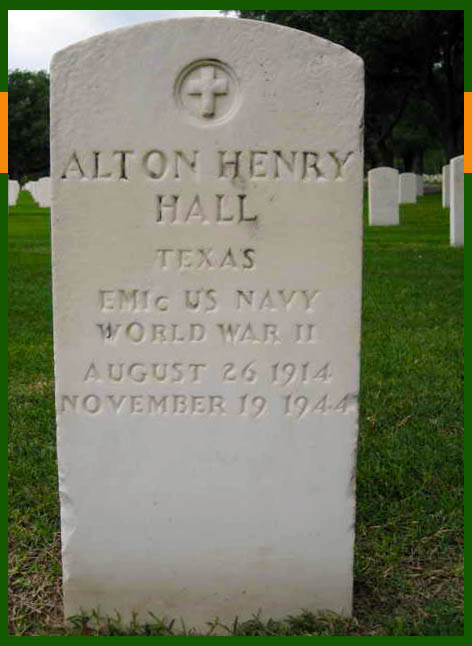

In January 1949, Alton Henry Hall’s remains returned to Texas, where he now rests in Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery in San Antonio.

Alton never married, as far as I can find records, so he likely didn’t have any children.

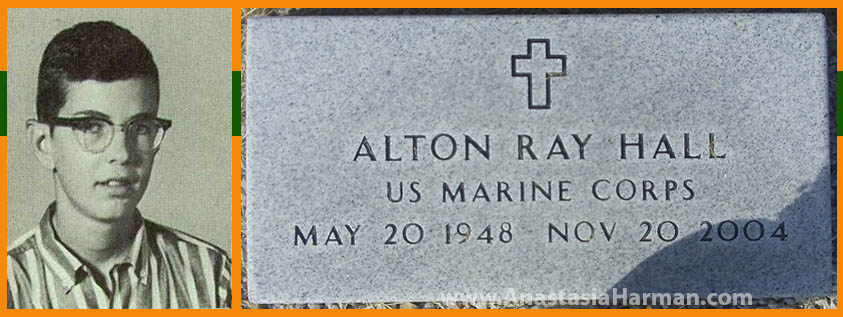

However, Alton’s brother Oliver had a son in 1948, who he named Alton. I suspect Oliver named his son after a brother who gave his all in defense of freedom. This younger Alton Hall, like his father and uncles, served his country as a US Marine.

The power of obscure finds

People put interesting things on the Internet.

Sometime during my POW research journey, I stumbled on the Center for Research: Allied POWs under the Japanese. This site provides at lot of resources to research WW2 POWs.

It’s got incredible information — if you’re willing to dig. And I’ve done a lot of digging.

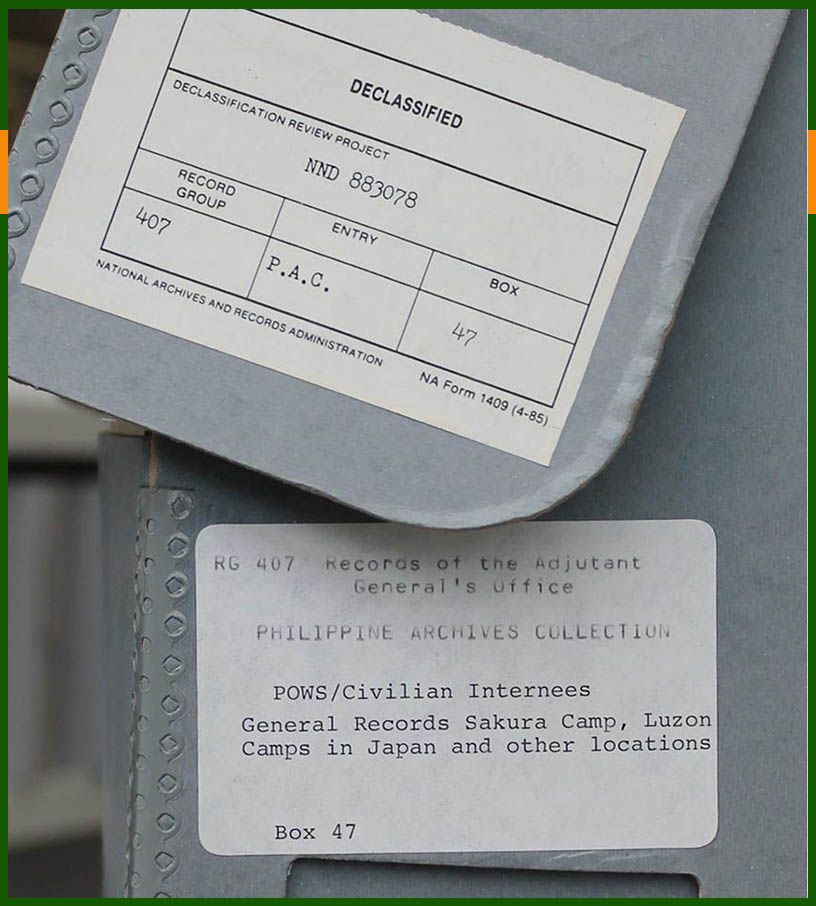

With Alton Hall, I knew which POW camp he died at. So I visited the Center for Research site to find context about the Sakura camp in Manila.

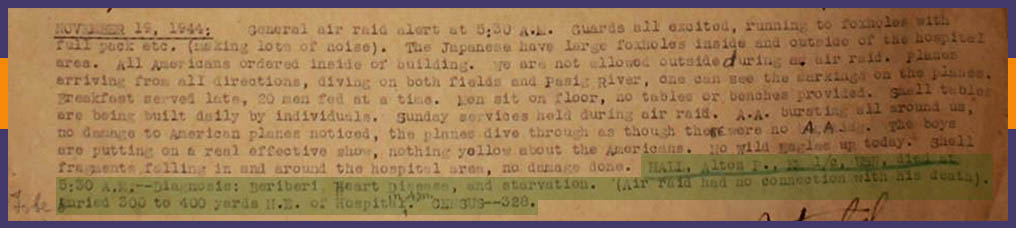

I discovered a 125-page PDF of — formerly classified — camp records. Here’s the first page:

This PDF is from a collection at the US’s National Archives. Someone took pictures of each record within this box, put them into a PDF, and made it available online.

I scrolled through 100+ pages of camp rules/regulations, medical personnel and patient lists, memos to Japanese officials, payment and inventory lists, and more.

Starting on page 116, I discovered the camp’s Official Diary, written by the American camp director (who was himself a POW). He made a short entry for each day, offering info about the camp’s conditions and the dates/times of air raids.

And then I got to the entry for Sunday, November 19, 1944:

At the bottom, underlined in pencil, was Alton Hall, with details about his passing!

Talk about a needle in a haystack. But, oh, to have this document, this piece of information, for me it’s just priceless. It allows me to tell Alton’s full story.

The lesson for your tree is that obscure things on the Internet can add SO much to your family tree. Finding them can be challenging and time consuming. But if/when you do find something like this, well, it’s just amazing.

Read Next

Sources

- Alton Henry Hall entry, National Cemetery Administration. U.S. Veterans’ Gravesites, ca.1775-2006 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2006. Original data: National Cemetery Administration. Nationwide Gravesite Locator. Accessed 30 March 2020.

- Alton Henry Hall entry, U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962, database on-line, Ancestry.com Operations, Original data: Interment Control Forms, 1928–1962. Interment Control Forms, A1 2110-B. Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985, Record Group 92. The National Archives at College Park, College Park, Maryland. Accessed 30 March 2020.

- Alton Henry Hall, Naval Receiving, 29 Feb 1940, U.S. World War II Navy Muster Rolls, 1938-1949 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2011. Original data: Muster Rolls of U.S. Navy Ships, Stations, and Other Naval Activities, 01/01/1939-01/01/1949; A-1 Entry 135, 10230 rolls, ARC ID: 594996. Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, Record Group Number 24. National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. Accessed 30 March 2020.

- Alton Henry Hall memorial, Find a Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/739788, accessed 1 April 2020.

- Alton H. Hall, Report of Death, Bilibid Hospital for Military Prison Camps, to Sugeon General, US Army, Washington, DC, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/80564705, accessed 1 April 2020.

- Alton Henry Hall, World War II Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard Casualties, 1941-1945 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007. Original data: State Summary of War Casualties from World War II for Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard Personnel [Archival Research Catalog]; Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, Record Group 24; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. Accessed 31 March 2020.

- Alton Henry Hall, World War II Prisoners of the Japanese, 1941-1945 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: National Archives and Records Administration. World War II Prisoners of the Japanese File, ARC IDs:718969, 731002, and 2123836. National Archives at College Park. College Park, Maryland, U.S.A. Accessed 30 March 2020.

- Alton Henry Hall, World War II Prisoners of War, 1941-1946 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2005. Original data: National Archives and Records Administration. World War II Prisoners of War Data File [Archival Database]; Records of World War II Prisoners of War, 1942-1947; Records of the Office of the Provost Marshal General, Record Group 389; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. Accessed 31 March 2020.

- Alton Ray Hall memorial, Find a Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/80564705, accessed 1 April 2020.

- Entries for November 15, 16, and 19, 1944, “Official Diary,” Hospital Sakura Detached Camp, Prisoner of War Disclosure #24, page 99, Philippine Islands, part of the POW/Civilian Internees, General Records Sakura Camp, Luzon Camps in Japan and other locations, Box 47, Philippine Archives Collection, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, RG 407, found online at http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/philippines/PHILIPPINES_Ft_McKinley_Sakura_Prison_Hospital_RG407Bx47.pdf, accessed 1 April 2020.

- Henry A. Hall family, 1930 United States Federal Census, database online, Ancestry.com, Original data: United States of America, Bureau of the Census, Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930, Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1930, T626, 2,667 rolls, accessed 31 March 2020.

- Henry A Hall obituary, Abilene Reporter-News, 16 January 1968, Abilene, Texas, found online at Newspapers.com, accessed 31 March 2020.

- Oliver Franklin Hall Sr memorial, Find A Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/80564729, accessed 31 March 2020.

- Orval L. Hall entry, U.S. WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942-1954 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2019. Original data: Hospital Admission Card Files, ca. 1970 – ca. 1970. NAI: 570973. Records of the Office of the Surgeon General (Army), 1775 – 1994. Record Group 12. The National Archives at College Park, MD. USA. Accessed 2 April 2020.

- “Roster of Personnel,” Hospital Sakura Detached Camp, Prisoner of War Disclosure #24, page 38, Philippine Islands, part of the POW/Civilian Internees, General Records Sakura Camp, Luzon Camps in Japan and other locations, Box 47, Philippine Archives Collection, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, RG 407, found online at http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/philippines/PHILIPPINES_Ft_McKinley_Sakura_Prison_Hospital_RG407Bx47.pdf, accessed 1 April 2020.

Images

- Image 1: Alton Hall picture. Memorial for Alton Henry Hall, uploaded by Tx Oma, Find a Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/739788, accessed 1 April 2020.

- Image 2: USS Canopus. Official US Navy image, image number 80-G-1014615, in the collections of the US National Archives and Records Administration, found online at Naval History and Heritage Command, Department of the Navy, https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/OnlineLibrary/photos/sh-usn/usnsh-c/as9.htm, accessed 19 August 2019.

- Image 3: Proteus engine room. “USS Proteus AS 19 Page 2,” Submarine Tenders, Tender Tale United States Navy, found online at http://www.tendertale.com/tenders/119/119-2.html , accessed 13 March 2020.

- Image 4: POWs Marching through Manila. From “USAFFE Troops Taken War Prisoners in Corregidor March thru Manila,” The Sunday Tribune, Manila, Philippines, 7 June 1942, page 3, found online at Pinterest, https://www.pinterest.com/pin/120682464999523850/?nic=1, accessed 15 October 2019. Note: This was a Japanese-controlled newspaper.

- Image 5: Drawing of Ft. McKinely. “Review at Fort William McKinley,” postcard, found online at https://www.cardcow.com/203852/review-at-fort-william-mckinley-manila-southeast-asia/, accessed 4 April 2020.

- Image 6: Nipa Mat. Licensed from Adobe Stock Images.

- Image 7: Sakura camp map. Hospital Sakura Detached Camp, Prisoner of War Disclosure #24, page 107, Philippine Islands, part of the POW/Civilian Internees, General Records Sakura Camp, Luzon Camps in Japan and other locations, Box 47, Philippine Archives Collection, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, RG 407, found online at http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/philippines/PHILIPPINES_Ft_McKinley_Sakura_Prison_Hospital_RG407Bx47.pdf, accessed 1 April 2020.

- Image 8: Alton Hall headstone. Memorial for Alton Henry Hall, uploaded by CynC, used with permission, Find a Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/739788, accessed 1 April 2020.

- Image 9a. Alton Ray Hall yearbook photo, Comanche High School, 1965, Comanche, Texas, U.S., School Yearbooks, 1900-1999 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Accessed 4 April 2020.

- Image 9b. Alton Ray Hall headstone. Alton Ray Hall memorial, Find a Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/80564705, accessed 1 April 2020

I want to thank you for this article. I am the grandnephew of Alton Henry and I was very close to my uncle Alton Ray, he always wore a ring with an A on it that belonged to Alton Henry. I have the Navy photo of his graduation class and I actually took the 1st picture that you have of him and submitted it and his headstone photo years ago to On Eternal Patrol.com. My family and I greatly appreciate your research and taking the time to compile this.

Jordan, Thank you for leaving this comment. My greatest desire if for these servicemen to be honored and remembered, and I’m especially excited when I hear that their family members find the bios I’ve written (and are happy with the bios). So, thank you again for reaching out.