Note: This chapter contains mildly graphic descriptions of war and disease that some readers may finding disturbing

While it eventually happened that we were taken away from Corregidor, it did not prove to be done in the manner we expected.

The first Corregidor POW march

The next morning, May 8, 1942 [two days after the US surrendered Corregidor], the Japs began shouting and screaming at everyone in the entire area to immediately form into marching columns on the road. Those who had anticipated this move had already prepared small packs or barracks bags with a few clothes and other essentials, and carried them along.

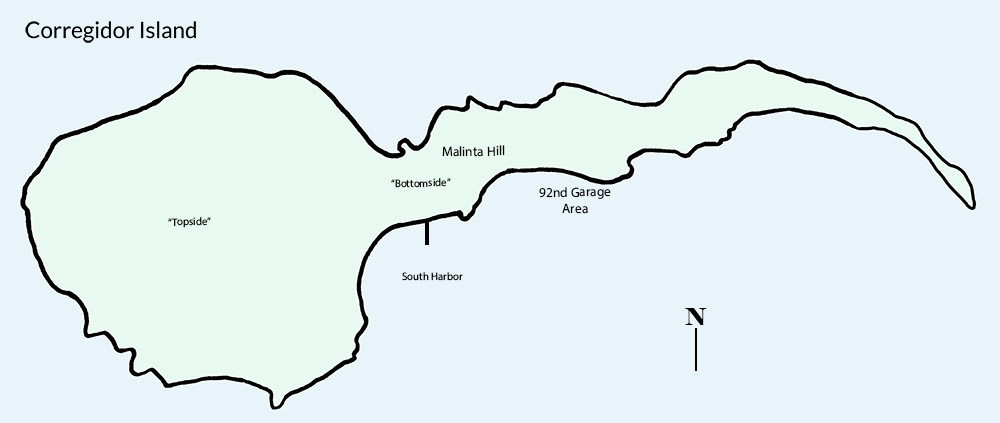

In a few moments, we were marching up the sloping road along the south side of Malinta Hill, eastward into the broiling sun, for a distance of about one mile.

It was an arduous journey for many who were half well and ailing principally from malaria, even at this early period. As the leading battalions disappeared from sight over the brow of an eastern ridge, it reminded one of lost souls vanishing into oblivion.

Descending down the steep hills nearing the end of our journey, we passed numbers of black and bloated bodies of our unburied dead lying on the dry dusty roads. They had fallen during the battle of Monkey Point two days before, and the Japs had not as yet permitted burial.

Decomposition, which is rapid in the tropics, was already setting in. This had brought swarms of big blue flies which amassed over them, concentrating on their faces which were exposed.

“A hot oven” — the Army 92nd Garage

Our destination was a small, almost sea-level, area about six hundred feet square and flanked on the eastern side by two or three large and old galvanized iron buildings painted black.

They had been perforated with hundreds of holes due to previous enemy bombings and strafing runs. There were a few bomb craters on the perimeter of this open space.

This place was known as the Army 92nd Garage.

Steep hills rose up almost abruptly from three sides. The fourth side opened to the sea bay on the south which was strewn with large rocks and boulders.

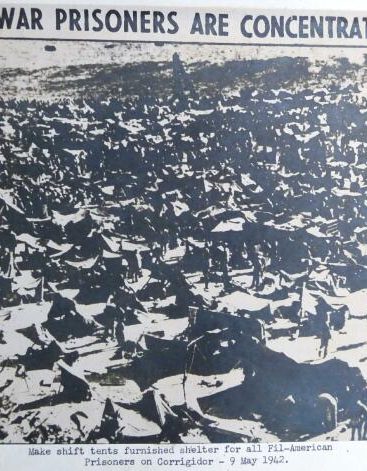

For the next seventeen days this tiny packed square was to be the home of approximately nine thousand American uniformed fighting forces that included a few hundred civilians and about two thousand uniformed Filipino soldiers and civilians.

This area held the heat of a hot oven. It was the hottest and driest time of the year, just before the rainy season.

Inadequate, makeshift shelter

These galvanized buildings were heavily covered with dirt and filth. After setting up a First Aid Station and various work detail centers, little room was left for general occupancy in the north section; and the south was entirely occupied by the Filipinos who were segregated into that division and the adjacent areas.

Most of us settled down on the ground outside. There were no facilities whatsoever here.

We were protected from the sun by small sections of canvas shelter halves, blankets, or any other covering we had the forethought to carry with us. These we rigged up on some small sticks we had gathered from the sparse growing brush nearby and what we could salvage from the general trash lying about.

Under these small inadequate shelters, we crowded together in an attempt to share what little protection they provided. Needless to say, having no pads or mattresses, we slept on the ground. Officers and enlisted men were branded with a number painted on the back of their shirts.

The first work detail — burying the dead

One of the first work details assembled was sent out to bury those dead comrades who we had passed on our march to camp.

Due to the decomposed condition of the bodies, wire was attached to a leg and the corpses dragged a short distance to a shallow grave for burial. One of the Army chaplains was present and conducted funeral services as the burials took place.

We also buried all Jap dead whom they did not burn. Returning from a food foraging expedition, I was among those who witnessed the burning of the bodies of six Jap officers. A large funeral pyre was built and upon it were placed these corpses. I understood ashes were to be sent back to Japan to be placed in their respective shrines, a very common practice accorded to their soldier dead.

Foul water and parched throats

Very little drinking water was available at this point; what there was occupied a shallow well. After only a couple of dozen bucketfuls were drawn, the well became nearly dry. We would patiently wait a half-hour or so until water seeped in sufficiently to begin operations again. It was very brackish and not pure enough to drink without treatment of iodine.

After several days a small one-inch water pipe was laid to our present internment area. There was little pressure at best. It flowed very slowly most of the time and at certain periods was shut off completely, long before the wants of many of us had been satisfied.

Although it was tepid and ordinarily foul tasting, under the circumstances it tasted good to parched throats, although one treated it against infection if they had the necessary chemical. Some drunk without the precaution on a chance nothing serious in the way of intestinal parasites would result.

The never-ending water line

There was always a water line. Here every type of container, old or new, that could be salvaged from the rubble about us was pressed into use. Gasoline tins, meat cans, gasoline drums, metal cylindrical powder cases, military water containers and canteens, washing buckets: all saw duty to obtain this precious liquid.

We would stand in the water line sometimes as long as three hours in the fierce heat before our turn arrived. Those few individuals constituting the small group to which I was attached (a sort of family unit) would each take turns—”sweating” out the water line in relays after an hour of standing in the torrid heat. This line was continuous all day and night.

The water was only available in quantities for drinking and cooking purposes. None was available in which to wash clothes or to bathe. We attempted to wash clothes in salty sea water and with the aid of a good sunning it helped, although it was far from a satisfactory job.

Foraging for food

No food was furnished to us by the Japs at this time.

A little later on some uncooked food was brought into the camp by our own working parties for general rationing from a central point; but it was wholly inadequate and not systematically distributed for the most part, at any time.

Reluctantly the Japs finally gave us permission to forage for food and water among our surrendered installations a mile away on Malinta Hill.

This [food] was now war booty of the Japanese, and what little we did salvage this way was by sufferance only. They were not very disposed to let us pass the posted guards, in order to salvage clothes and other badly needed items strewn about the tunnels in and around the abandoned fox holes, pill boxes, and dug in positions.

Groups of one hundred men under the leadership of a field officer not below the grade of Lieutenant Colonel (identified by a white arm band covered with Japanese characters) were permitted to travel for water and to the upper regions for necessities. We were warned that the groups must return intact.

Upon arriving back at the camp, if an American was slow in returning due to being burdened with food or water supplies, at times was beaten with a rifle butt.

The ravaging diseases begin

Malnutrition silently started to work.

And already the diseases dysentery, diarrhea, and malaria began ravaging many of our number, although this was mild in comparison to what lay ahead. We had to take care of each other as best we could.

Our medical officers had a little medicine and distributed it the best they knew how; but they were totally without many essential drugs. The sick and weak and those who frequently fainted from heat prostration in this oven of a place lay around the small First Aid Station.

“Inhumanly turned out of the hospital”

Occasionally one or two were permitted to be littered back up the hills for temporary treatment at the hospital in the [Malinta Hill] tunnels where there were yet many of our worst cases. However, a lot were discharged prematurely and sent down to us in order to make room for Jap sick and wounded who were also being attended by our doctors.

Many of these afflicted Americans were far from well but, nevertheless, had been inhumanly turned out of the hospital. It was pitiful indeed to see some of those men who were so sick, many with high fevers, just laying there in the dirt without proper food, medicine, and proper attention in that unbearable heat.

A certain confusion and chaos reigned everywhere. An attempt to bring about a semblance of order was only partially effective.

Flies, of course, were everywhere. The large red-headed blue bottle species, much larger than the ordinary blowfly here in the United States, as well as the small type house fly, multiplied by the thousands because of the ideal breeding places in the open straddle trench latrines. Although a certain amount of fire and disinfection was possible to eliminate them, it was too meager, and swarms of flies carrying death-dealing infections continued to breed by the thousands.

Hot, cloudless, stagnant days

The men took advantage to keep cool form the broiling tropical sun by remaining nude in the bay water at depths up to their necks.

We were continually dripping perspiration as the sun overhead hung in a cloudless sky like a fiery ball during those days. Not a breath of air stirred during most of the day, and, at times, we were almost suffocating.

How we watched and waited; and how slowly the sun moved across the heavens. And when, at about six p.m., it slipped below Malinta Hill to the west, we only then had surcease from its flaming rays. By midnight it became a little cooler so one could snatch a few hours of sleep without perspiring before the process was begun all over again.

Due to poor sanitation and a lack of interest in personal hygiene, the ocean water and beaches in our immediate vicinity became polluted. Some of the filthy individuals defecated into the sea while bathing, which contributed to further infections among us.

Many men were afflicted with impetigo, or locally referred to as “Guam Blisters”; and, being very contagious, the conditions were ideal for its spread until hundreds were infected in a very short time. In these cases the sores and ulcers grew in size with a yellow pus-like scab formed or open lesions resulted. It was sickening to see; and very painful to endure.

The rains come and the POWs leave

In the early hours of the morning of May 23, 1942, the first torrential rain storm of the season fell. Daylight found us huddled together, completely drenched as only a tropical deluge can saturate one.

Dog tired from the lack of rest the previous night, nevertheless we were enthused a little to learn that orders had been received to evacuate this concentration area.

We retraced our steps to “Bottomside”.

As we marched along—a grim, dejected lot—we passed within the shadow of the church. As a result of the constant bombing, practically all the surrounding buildings were reduced to rubble. However, the little stone chapel appeared largely undisturbed and stood tranquil amid the chaos and ruin. Through the partly demolished walls one glimpsed the large heavy-paged bible upon the pulpit, a comforting influence.

After being herded together again for several hours under the ever-present blazing sun, we were marched in groups down to the small pier extending into South Harbor. [See image 7.]

In various small boats and launches we arrived alongside three old and extremely filthy Japanese troop ships.

While on board we endured the usual pastime — repeated searching of our persons by the Jap crews.

Although my watch had been taken from me on round one, they never did find my meager supply of Filipino currency hidden up under my cap insignia, guarded by the American eagle.

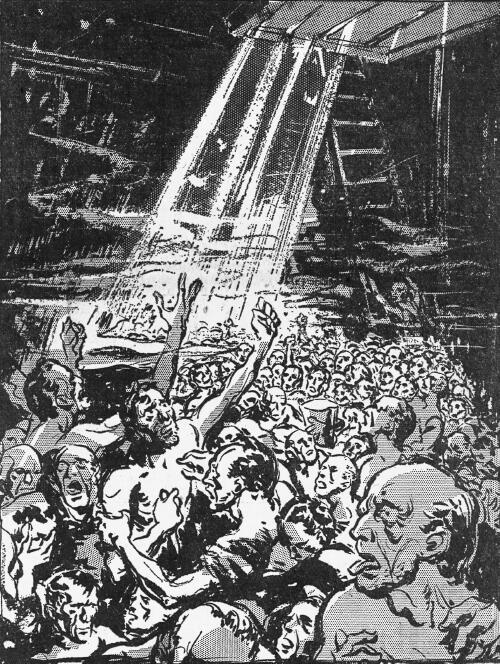

Onboard a Japanese hell ship

The ship’s hold, into which we were jammed, was equipped with bunk tiers covered by vermin-infested straw matting upon which, undoubtedly many times previously, had lain dirty Jap troops and coolies.

We lay shoulder to shoulder.

The air was hot, sick, and foul. There was no ventilation except from the small booby hatch thru which we gained entrance.

Literally every foot of space was utilized, and many were compelled to spread over the top hatches like a “starfish spread out over a clam,” to use an “old salt’s” expression. Others crammed into the small weather deck spaces. Decks were bare, rusty metal.

That night it rained again, and we who were obliged to lie on the bare iron deck were anything but a comfortable lot.

Sailing for Manila

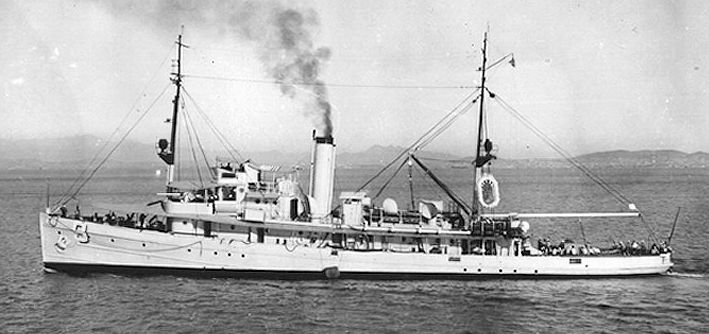

The following morning, Sunday, May 24, 1942, the three prisoner-of-war ships moved away from anchorage in South Harbor and slowly steamed thru the channel heading for Manila, twenty-eight miles to the eastward. We passed the former Yangtze River American gunboat “USS Guam” and the American minesweeper “USS Finch,” victims of Jap bombings and half submerged in the water on which Fort Hughes was located.

With the feel of a ship’s deck beneath my feet — even though the enemy’s — and the added “tonic” of a slight breeze prevailing from the South China Sea, my spirits were somewhat restored for the first time in many days.

While on board, there fell into our hands the Japanese-sponsored Manila Tribune, printed in English. It gave glowing accounts of the great victory of the Japanese Naval and Air Forces over our sea forces in the “Battle of the Coral Sea” a few days before; indicating the colossal losses we had suffered and stating that such a defeat as the United States forces had received is what will always happen to any power who dares challenge the invincible might of Nippon.

It also mentioned, wherever the Japanese Army went, peace followed in its wake.

All this, of course, was for the consumption of the Filipino populace; and to many natives it had its desired effect.

Read next

- See rare historical and modern photos of the Japanese siege and invasion of Corregidor in 1942. Also includes maps and aerials of the island to help illustrate where the POWs were.

- New here? Discover what the Luzon Holiday project is all about.

Please share

If you think Salm’s memoir is worth passing along to friends or family, we’d love for you to share the link to this post on social media or email. Thank you!

Images

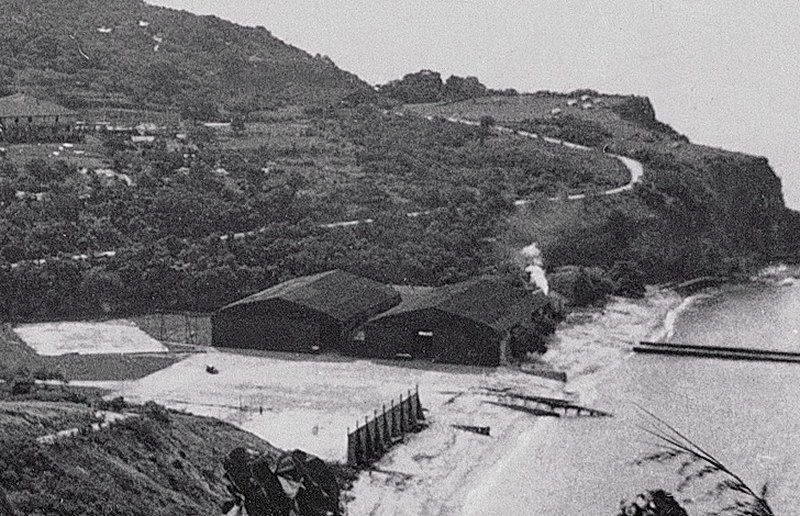

- Image 1: South Shore Road. Malinta Hospital after capture. Found online at John Moffitt, “The Malinta Tunnel, from Concept to Completion,” Dec 2012, Rediscovering Corregidor, http://corregidor.org/fieldnotes/htm/fots2-121224-2.htm, accessed 6 Aug 2019.

- Image 2: Pre-war pic of 92nd Garage Area. Found online at Corregidor Then and Now, Proboards, http://corregidor.proboards.com/thread/651/photos?page=7, accessed 6 August 2019.

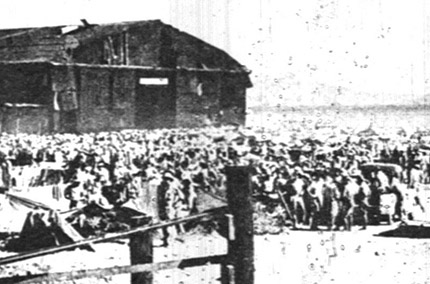

- Image 3: POWs at the 92nd Garage. Found online at Corregidor Then and Now, Proboards, http://corregidor.proboards.com/thread/651/photos?page=7, accessed 6 August 2019.

- Image 4: Brothers in Arms statue. Taken by Vanessa Workman, December 2016. Found online at “My Ghostly Encounters on Corregidor Island,” The Island Drum: Travel Blog of an Eclectic Expat, https://www.theislanddrum.com/ghostly-encounters-on-corregidor-island/, accessed 6 Aug 2019.

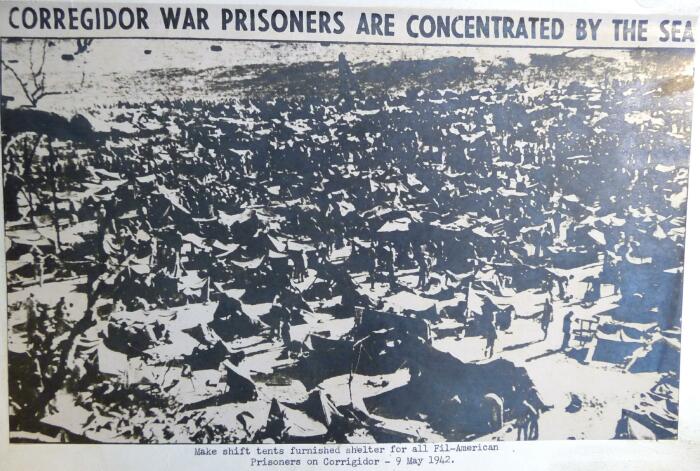

- Image 5: POW tents at the 92nd Garage. Found online at “Report of American Prisoners of War Interred by the Japanese in The Philippines, prepared November 1945, http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/philippines/pows_in_pi-OPMG_report.html, accessed 6 Aug 2019.

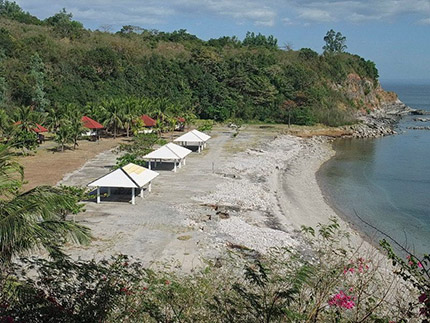

- Image 6: Resort at the 92nd Garage. Found online at Corregidor Then and Now, Proboards, http://corregidor.proboards.com/thread/651/photos?page=7, accessed 6 August 2019.

- Image 7: Map of Corregidor. Created by Anastasia Harman, August 2019.

Image 8: Japanese photo looking down on 92nd Garage. Taken by the Japanese Philippine Expeditionary Force, Mary 1941, found online at Corregidor.org, http://www.corregidor.org/J1/jpef/html/jpef_01_01_92nd_1_dsw.html, accessed 13 August 2019. - Image 9: POWs at the 92nd Garage. Found online at Corregidor Then and Now, Proboards, http://corregidor.proboards.com/thread/651/photos?page=7, accessed 6 August 2019.

- Image 10: Malinta Hospital after capture. Found online at John Moffitt, “The Malinta Tunnel, from Concept to Completion,” Dec 2012, Rediscovering Corregidor, http://corregidor.org/fieldnotes/htm/fots2-121224-2.htm, accessed 6 August 2019.

- Image 11: 2011 image of the Army 92nd Garage area. Taken by John Moffitt, November 2011, found online at “Field Notes: The North Side of Malinta Hill,” Rediscovering Corregidor, http://corregidor.org/fieldnotes/htm/fots2-111122-1.htm, accessed 6 August 2019.

- Image 12: Tropical rainstorm. Image licensed from Adobe Stock.

- Image 13: Bottomside. Found online Louis Morton, “The Siege of Corregidor,” in The War in the Pacific: The Fall of The Philippines (Washington, DC, Center of Military History, US Army, 1953), found online at https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/5-2/5-2_27.htm, accessed 13 August 2019.

- Image 14: POWs on a hell ship. From George Weller, “Death Cruise, Part 2: Yanks Go Mad on Agony Ship,” Chicago Daily News, November 9, 1945, found online at “News from the Past,” POW Resources, http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/newspaper/newsfrompast-cruiseofdeath.html, accessed 13 August 2019.

- Image 15: USS Finch. Image in the collection of the US National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, DC, found online at Japanese Patrol Boats, http://www.combinedfleet.com/PB-103_t.htm, accessed 13 August 2019.

Highly detailed account of the suffering our brave soldiers endured during captivity in the Philippines during WW2

I would strongly recommend joining this group for mutual information

I am a WW2 US Army orphan my father was killed in action on Bataan January 1942 and am very interested reading first hand account of that tragic period in our history

Dr Rios, Thank you for reaching out. Bataan was a horrible experience, and I am so sorry you lost your father to it. I’m glad to have you here and to connect with you.