“And, for God’s sake, don’t let the Japs get any of those submarine stores!”

The mission was straightforward enough — destroy the US Navy’s submarine warehouses in Manila.

This was Christmas Eve 1941. And tensions were high, with Americans hustling around Manila city in The Philippines.

Except this wasn’t the usual holiday rush.

No, it was the frantic movements of the American military pulling out of the city. Retreating to the wilds of the Bataan Peninsula across the bay from Manila. Staying ahead of the fast-moving Japanese advance during the early days of WW2 in The Philippines.

All, that is, except for Navy Storekeeper Arthur Lazcano and his three shipmates: Gordon Fontaine, John Burk, and William Patton.

No, retreat wasn’t their mission. Instead, they were headed back into the city that would soon be occupied by the enemy.

A young San Diego sailor

Arthur William Lazcano was a southern California boy born January 20, 1918. He spent a good portion of his early years in San Diego. His father died in 1930, at the start of the Great Depression, when Arthur was 12. And the family appears to have struggled financially.

When he was 18, just months out of high school, Arthur enlisted in the US Navy. Six months later, he was onboard the USS Canopus.

Lazcano was a Navy Storekeeper. His job was to help keep track of Navy supplies, an especially important and busy job on the Canopus since she was a submarine tender.

Before World War 2, the ship sailed mainly between China and The Philippines carrying food, fuel, torpedos, supplies, maintenance equipment, and even relief crews for various US submarines.

Front-row seat to WW2 in The Philippines

Lazcano and the rest of the Canopus crew just happened to be in Manila Bay when the Japanese attacked The Philippines on December 8, 1941 — just hours after attacking Pearl Harbor.

America was at war. And Storekeeper 1st Class Lazcano had a front-row seat.

Within a few weeks, fast-moving Japanese ground and air forces had already overrun most of Luzon (the island that Manila is on). The war was not going well for the Americans.

On Christmas Eve 1941, the Canopus was docked at Manila, but the Americans had started pulling back to the Bataan Peninsula on the other side of Manila Bay. The Canopus needed to leave, and soon.

But this urgent escape was a problem for the Canopus: First, the ship needed supplies. Second, the Canopus had submarine and other Navy supplies in bodegas (warehouses) in Manila. Supplies the Americans didn’t want to fall into Japanese hands.

Left behind in war-torn, Japanese-occupied Manila

Arthur Lazcano and 3 other Canopus Storekeepers — William Patton, Gordon Fontaine, John Burk — rushed around Manila trying to find various supplies, including oxygen, acetylene, and Freon (essential for submarines).

Time ran out. The Canopus had to leave. Within days Japanese forces would overrun Manila, but the submarine and other Naval supplies could not get into their hands.

So Lazcano and the other Storekeepers were left behind as the Canopus sailed silently into Manila Bay under cover of darkness.

“Take care of yourselves,” Chief Warrant Officer Alma Salm, their immediate superior, hurriedly told Lazcano. “And, for God’s sake, don’t let the Japs get any of those submarine stores stowed in the bodegas!” (Bodegas are warehouses, just FYI.)

And that was the last time the Canopus saw Arthur Lazcano.

Back home: An unbelievable message to Lazcano’s family

Lazcano was Missing in Action.

At least that’s what the Canopus’s Captain Earl Sackett recorded in March 1942, 3 months after Lazcano and his shipmates disappeared in to a war-torn Manila. Actually, that captain’s specific words were: “Missing since the beginning of the war.”

And, soon, news reached his mother and sister in San Diego — Arthur’s ship sank. He was missing in action. Presumed dead. (BTW, the Canopus did eventually sink, but Lazcano wasn’t on board.)

Imagine the heartbreak. First Elizabeth Lazcano loses her husband in the early 1930s. Then, a decade later, this raging war takes her only son.

For an entire year they would have mourned. And then . . . well, something strange.

The Navy Department contacted Lazcano’s sister in April 1943 with unexpected news: Arthur was alive. In a prison camp. In Japan.

Except . . . that wasn’t exactly true, either.

Sabotaging and fooling the Japanese

Let’s back up. All the way to December 24, 1941. WW2 had just arrived in The Philippines

The Canopus left Manila. And Lazcano and his 3 shipmates — Burk, Patton, and Fontaine — had a mission: destroy the Navy bodgeas full of submarine parts.

Just to be clear, they destroyed anything potentially useful to the invading Japanese. So that the Japanese couldn’t use it. That’s what we call sabotage.

And the 4 storekeepers got it done, destroying not only the Canopus‘s bodegas, but supplies in other Navy bodegas as well. But, by then, it was too late to rejoin the ship. So they disguised themselves as American civilians, and entered the Santo Tomas Civilian Interment Camp in Manila.

And that’s where, a year later in spring 1943, the Japanese discovered that Lazcano and company were not civilians, but American military.

And they (the Japanese) were not pleased.

Long story short, Lazcano, Burk, Patton, and Fontaine then spent 73 days in a dungeon, until transferred to the main Philippines POW camp (called Cabanatuan) in summer 1943. There the 4 men reunited with an astonished Alma Salm, the Canopus‘s Chief Storekeeper.

(Of course, there’s more to the story, and you get the details about life in Santo Tomas Internment Camp in Gordon Fontaine’s bio.)

So, in April 1943, when Arthur’s mother and sister received word that Arthur was in a prison in Japan, he was actually a WW2 prisoner in The Philippines. Details, details . . .

Transferred to Osaka, Japan

However, Lazcano eventually did wound up in a prison in Japan. (And this time with out his 3 Canopus shipmates.)

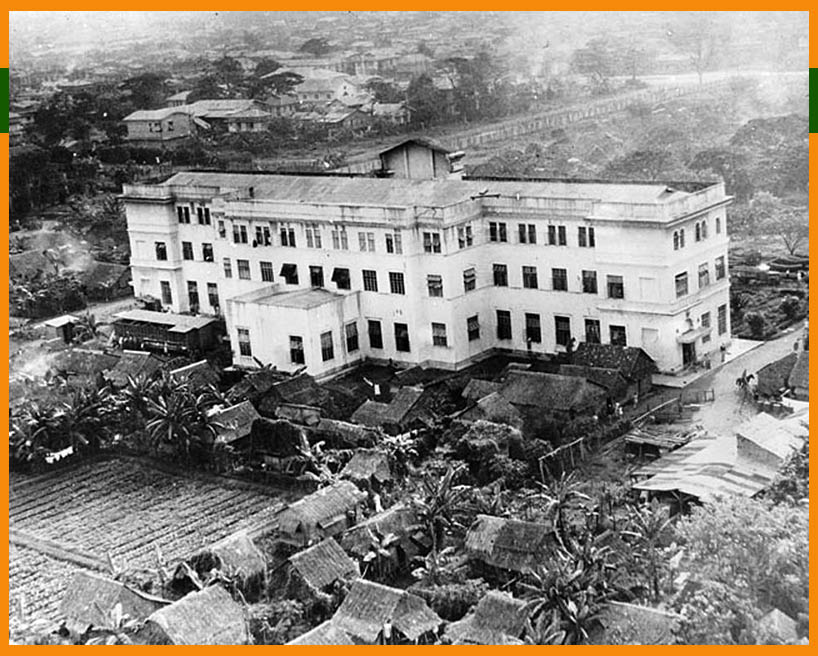

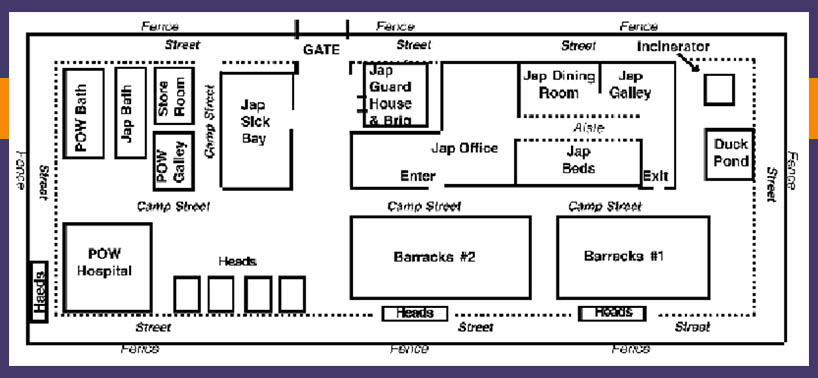

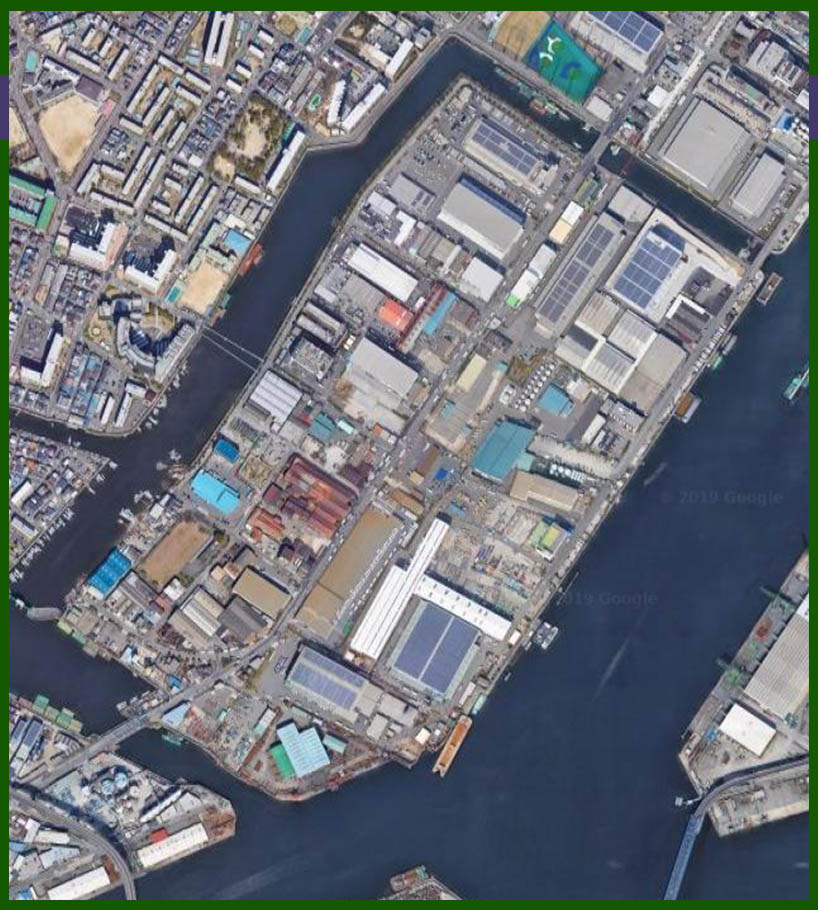

He was in the Osaka Main Camp Chikko.*

Osaka is a port city on Japan’s main island (the same island that Tokyo is on). Camp Chikko was on the waterfront, meaning it was in the middle of vital military targets.

In other words, places the Americans and other Allies would want to bomb.

And Lazcano would have been in the camp when American forces did bomb it on June 2, 1945. Everything burned.

Prior to the bombing, Lazcano and other POWs worked on the Osaka docks. Starting at 8 am, they worked until 8 pm loading and unloading ships and train cars, working in warehouses, and transporting various materials.

All things considered, the POWs at Chikko seem to have been given better clothing, shelter, treatment, and food than those in Philippine camps.

For a few months after the camp bombing, Lazcano and the Chikko POWs were moved to several other locations — still along the Osaka waterfront. Finally, in early September 1945, Storekeeper Lazcano was liberated by American forces.

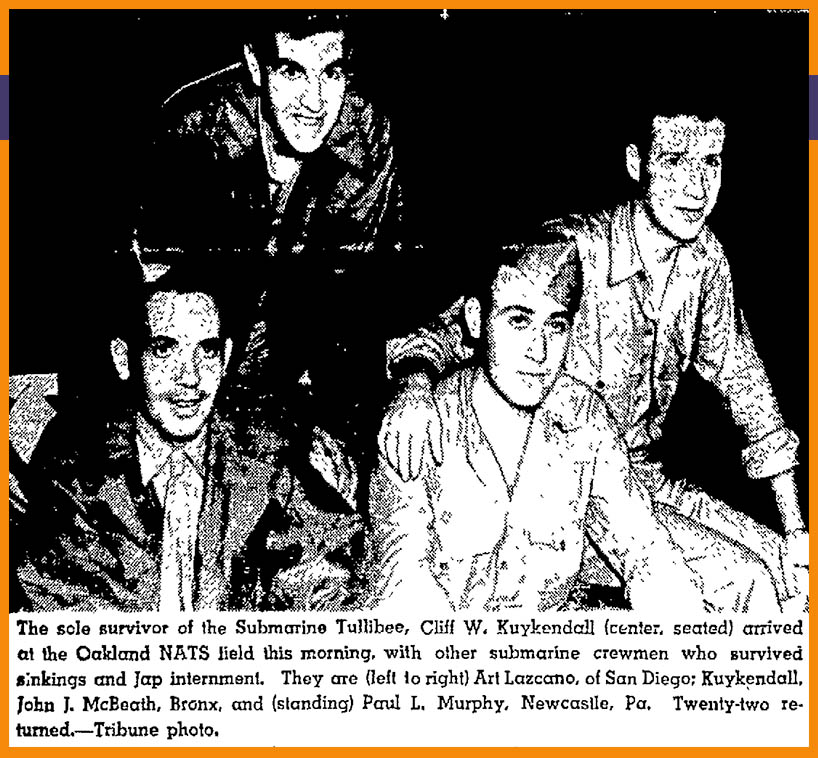

After 3 years and 9 months as a prisoner of war, Arthur Lazcano arrived in Oakland, California, on September 12, 1945 — a free man.

And back to The Philippines

In 1946, Arthur married Betsey Skinner — a college graduate and commissioned officer in the US Navy WAVES.

A couple years later, Lazcano found himself in familiar territory: stationed in The Philippines from at least 1948 through 1950. Lazcano made the Navy his career, serving in the Korean War and eventually retiring as Lt. Commander.

In 1964, a 46-year-old Arthur Lazcano graduated from Cornell University. By 1969 he was director of Financial Aid at Ithaca College in Ithaca, New York.

He died in Ithaca on December 14, 1998, just a month before his 81st birthday.

My #1 go-to tool for every POW

As you know, I write the stories of POWs who Alma Salm mentions in his memoir. But how do I discover what happens to a POW after capture? I mean, most the men appear only briefly in Salm’s memoir.

Well, here’s my secret — my #1 go-to resource for every POW.

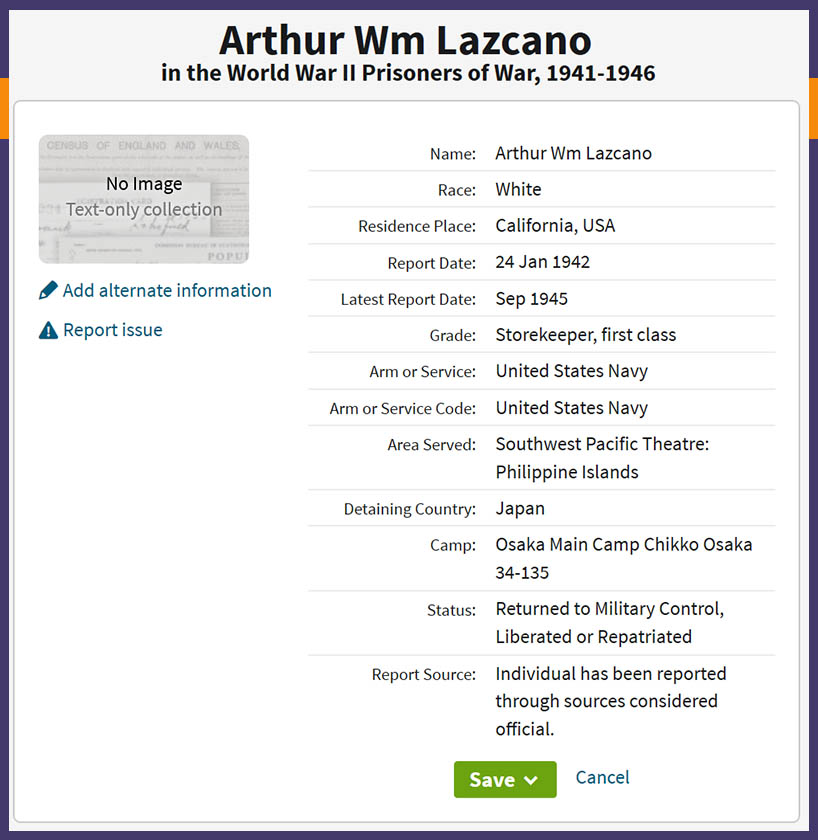

It’s a record collection on Ancestry.com called “World War II Prisoners of War, 1941-1946.” The info in it came from docs and reports compiled by the Red Cross. Here’s a screen shot for Arthur Lazcano’s entry:

Look at everything we learn about Lazcano! So much good stuff. But here’s what’s most useful in discovering his POW experience:

- Report date — The date he was reported to the Americans as being a POW.

- Latest Report Date — This is roughly the date he was liberated (or the date the Americans found out the POW had died).

- Camp — This is the last prison camp he was in. In other words — it’s the camp he was liberated from (or the camp where a POW died). I know the words and numbers seems like gibberish. But “34-135” is a code referring to a specific Japanese prison camp, in this case to the Osaka Main Camp in Chikko. I Google this info to discover more about the camp. And, if I’m lucky, how the POW got to that camp. (More on that in another post.)

- Status — Whether the POW was liberated or died. This helps me know what to look for next — ie, liberation info or death info. If a POW died, the status would read “Died as Prisoner of War.”

These 4 fields help me start piecing together the POW’s experience. I learn when he became a POW, the last camp he was in, and the approx. date of freedom or death. From there I can Google the camp names/codes to find more info and docs that help fill in the blanks.

You can search the “World War II Prisoners of War, 1941-1946” to discover stories about American WW2 POWs in your family.

If you do find your family’s POWs in this database, comment below and let me know what you learn!

Read Next

Can you help out?

Help us share Arthur Lazcano’s story by sharing on social media or emailing to friends. Thank you!

Notes

*Researching Japanese POW camps can be complex and confusing. Camps opened and closed. They moved locations but kept the same name. Some camps were destroyed, then moved, and then renamed. So the info contained here is what I’ve discovered based on my research.

Also, I haven’t discovered when he left The Philippines. He could have left The Philippines as early as September 1943, when a Japanese transport (aka “hell ship”) took 850 American POWs to Japan, some of them ending up in Osaka camps. Or it could have been a year later in fall 1944. That’s when the American military were starting to get some good traction in the war effort Japanese were starting to transfer POWs from The Philippines to Japan.

Sources

- “1920 US Federal Census,” database online, entry for Arthur Lazcano family, Ancestry.com, accessed 19 Oct 2011.

“1930 US Federal Census,” database online, entry for Elizabeth Lazcano family, Ancestry.com, accessed 19 Oct 2011. - “California Death Index, 1940-1997,” database online, entry for Elizabeth Lazcano, Ancestry.com, accessed 19 Oct 2011.

- “California Passenger and Crew Lists, 1882-1957,” database online, entry for Elisabeth S Lazcano, Ancestry.com, accessed 20 Oct 2011.

- “Chikko Camp Report,” Center for Research: Allied POWs Under the Japanese, found online at www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/osaka/chikko/warcrimes_report.htm, accessed 1 October 2019.

- “Deceased Classmates,” Cornell University Class of 1964, online at http://www.cornell1964.org/classmates-deceased.htm, accessed 19 Oct 2011.

- Image of Arthur Lazcano, Ithaca College 1969 yearbook, page 51, online database “US School Yearbooks, 1900-1999,” Ancestry.com, online at https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/yearbooksindex/, accessed 1 October 2019.

- “Man, Missing Year, Reported Captive,” Los Angeles Times, Thursday, April 8, 1943, page 9, digitized version online at Newspapers.com, found online at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/15038819/the_los_angeles_times/?xid=865, accessed 1 OCtober 2019.

- Memorial for William James Elliott, “Osaka Chikko POW camp, Japan, during the Second World War,” The Wartime Memories Project, found online at https://wartimememoriesproject.com/ww2/pow/powcamp.php?pid=2312, accessed 1 October 2019.

- “Miss Gustafson and Mr Skinner Wed Saturday,” Dunkirk [New York] Evening Observer, December 12, 1955, page 2, online at WorldVitalRecords.com, accessed 20 October 2011.

- “Navy Enlisted Job Description for Storekeeper (SK),” The Balance Careers, found online at https://www.thebalancecareers.com/storekeeper-sk-3345864, accessed 24 September 2019.

- “New Jap Torture Related by Liberees Here,” Oakland [California] Tribune, September 12, 1945, page 12, online at WorldVitalRecords.com, accessed 19 October 2011.

- Obituary for Betsey Lazcano, Observer, Dunkirk, NY, 5 March 2005, accessed through “United States Obituary Collection,” database online, entry for Betsey Lazcano, Ancestry.com, accessed 20 October 2011.

- “Osaka POW Camp #1,” Center for Research: Allied POWs Under the Japanese, found online at http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/osaka/chikko/chikko-main.htm, accessed 1 October 2019.

- “Portland,” Dunkirk [New York] Evening Observer, March 14 1950, page 5, online at WorldVitalRecords.com, accessed 20 October 2011.

- “Social Security Death Index,” database online, entry for Arthur W Lazcano, Ancestry.com, accessed 19 Oct 2011

- “US Public Records Index, Volume 2,” database online, entry for Yvonne L Rebholz, Ancestry.com, accessed 20 Oct 2011.

- “US Veterans Gravesites, ca1775-2006,” database online, entry for Arthur W Lazcano, Ancestry.com, accessed 19 Oct 2011.

- “US Veterans Gravesites, ca1775-2006,” database online, entry for Elizabeth Pearl Lazcano, Ancestry.com, accessed 19 Oct 2011.

- “US World War II Navy Muster Rolls, 1938-1949,” database online, entry for Arthur William Lazcano, Jan 1941, Ancestry.com, accessed 19 Oct 2011.

- “World War II Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard Casualties, 1941-1945,” database online, entry for Arthur William Lazcano, Ancestry.com, accessed 19 Oct 2011.

- “World War II Prisoners of the Japanese, 1941-1945,” database online, entry for Arthur William Lazcano, Ancestry.com, accessed 19 Oct 2011.

- “World War II Prisoners of War, 1941-1946,” database online, Ancestry.com, original data “World War II Prisoners of War Data File [Archival Database],” Records of World War II Prisoners of War, 1942-1947, Records of the Office of the Provost Marshal General, Record Group 389, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, College Park, MD., accessed 2 October 2019.

Images

- Picture of Arthur Lazcano. “New Jap Torture Related by Liberees Here,” Oakland [California] Tribune, September 12, 1945, page 12, online at WorldVitalRecords.com, accessed 19 October 2011.

- USS Canopus and submarines. Official US Navy image, image number 80-G-1014615, in the collections of the US National Archives and Records Administration, found online at Naval History and Heritage Command, Department of the Navy, https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/OnlineLibrary/photos/sh-usn/usnsh-c/as9.htm, accessed 19 August 2019.

- Burning Manila building. Acme Newspictures photograph, posted online by John Tewell, flickr, https://flickr.com/photos/johntewell/15893526446/in/photostream/, accessed 27 September 2019.

- Manila Pier 7. Posted online by John Tewell, flickr, https://flickr.com/photos/johntewell/6986754105/in/album-72157623238815677/, accessed 27 September 2019.

- North Bank of Pasig River. Image copyrighted by American Geographical Society Library (AGSL), University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, posted online by John Tewell, flickr, https://flickr.com/photos/johntewell/8516961975/in/album-72157623238815677/, accessed 27 September 2019.

- Aerial view of Manila. Army Air Corps photo, posted online by John Tewell, flickr, https://flickr.com/photos/johntewell/16047819972/in/photostream/, accessed 27 September 2019.

- Santo Thomas Interment Camp. US Army photo, public domain, Wikimedia Commons, found online at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Santo_Tomas.jpg, accessed 2 October 2019.

- Sketch of Osaka Chikko camp. Entry for “Chikko.” All-Japan POW Camp Group History, online at mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/fukuoka/fuk_01_fukuoka/fukuoka_01/CmpGroup.htm#OSA_13-B, image found online athttp://mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/fukuoka/fuk_01_fukuoka/fukuoka_01/CmpGroup.htm#OSA_13-B, accessed 1 October 2019.

- Satelite image of Osaka. Google Sightseeing, found online at www.googlesightseeing.com/maps?p=&c=&t=k&hl=en&ll=34.653156,135.455557&z=17, accessed 1 October 2019.

- Life Magazine cover. Life magazine, July 5, 1943, found online at https://books.google.com/books?id=SFAEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA17&lpg=PA17&dq=Arthur+William+Lazcano&source=bl&ots=w4pHlcARWl&sig=Av1rX50X5i3EuNJ0Lt7Wpy0au_U&hl=en&ei=CpKTTuLVIYni0QGR07GQCA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result#v=onepage&q&f=false, accessed 24 September 2019.

- 1969 portrait. Image of Arthur Lazcano, Ithaca College 1969 yearbook, page 51, online database “US School Yearbooks, 1900-1999,” Ancestry.com, online at https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/yearbooksindex/, accessed 1 October 2019.

- Arthur Lazcano’s Grave. Memorial page for LCDR Arthur William Lazcano, Find-A-Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/94341678, accessed 24 September 2019.

- WW2 POW info screenshot. Taken from “World War II Prisoners of War, 1941-1946,” database online, at Ancestry.com.