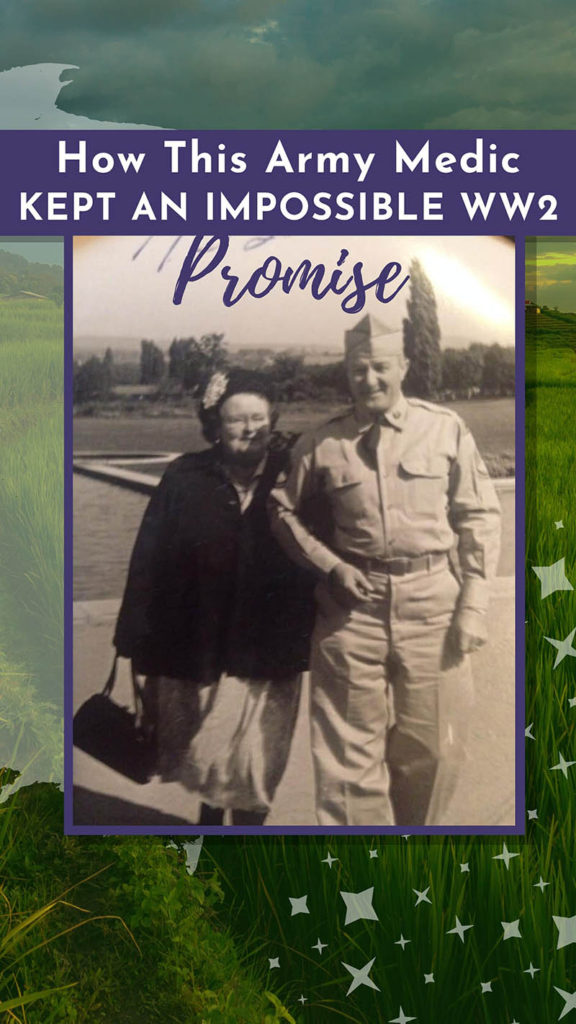

“When my brother enlisted for foreign service, he told me he’d be back.”

Mrs. D.T. Griffith knew that her brother, Corporal Benjamin Rush, was in The Philippines at the outbreak of WW2 in the Pacific. She knew that the Japanese had attacked that island nation. Knew that he was likely in a war zone.

But she didn’t know if her brother was safe. If he was alive. If he could even keep his promise to return home.

Finally, in early April 1942, a letter arrived. Dated January 30, 1942, from Fort Mills on Corregidor island in Manila Bay. Everything is alright, Corporal Rush told his family. He was well and happy.

Relief! “If he can send mail to me, I can to him,” Mrs. Griffith said. So she bought her brother a subscription to the Dallas Morning News, so he could keep up with the going ons at home.

But Corporal Rush would never receive his morning papers and any letters his sister sent.

And Mrs Griffith, well, the only news she’d hear about her brother for the next 2 years didn’t come from him.

Texas panhandle roots

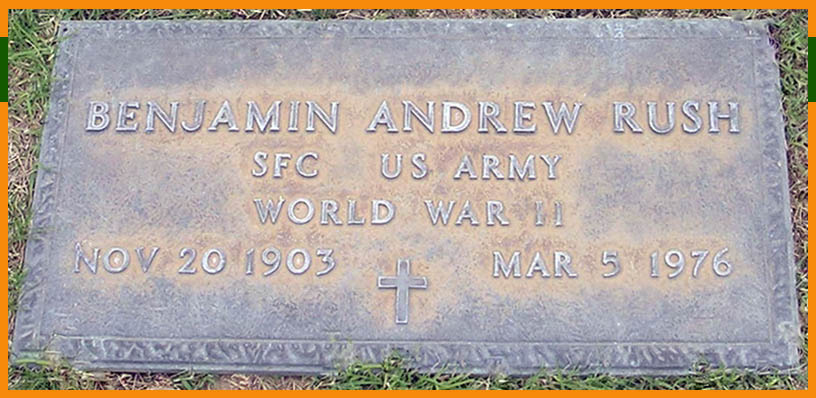

Benjamin Andrew Rush was born November 20, 1903, on a Texas panhandle ranch, one of six children of Benjamin and Maud Rush. Father Benjamin was among the first white settlers in the panhandle’s Tule Canyon, just south of Amarillo, Texas.

Andrew, as Benjamin Jr was known, spent his childhood on the family farm and attended Terrell Military College after graduating high school in the early 1920s.

After his father’s death in 1928, Andrew worked on a neighboring family’s farm followed by 2 years at a teachers’ college near Dallas.

Then, in 1934, the 31 year old enlisted in the US Army’s Medical Department. He spent time at Ft. Sill in Oklahoma and at Camp Bullis outside San Antonio, Texas.

And then came WW2.

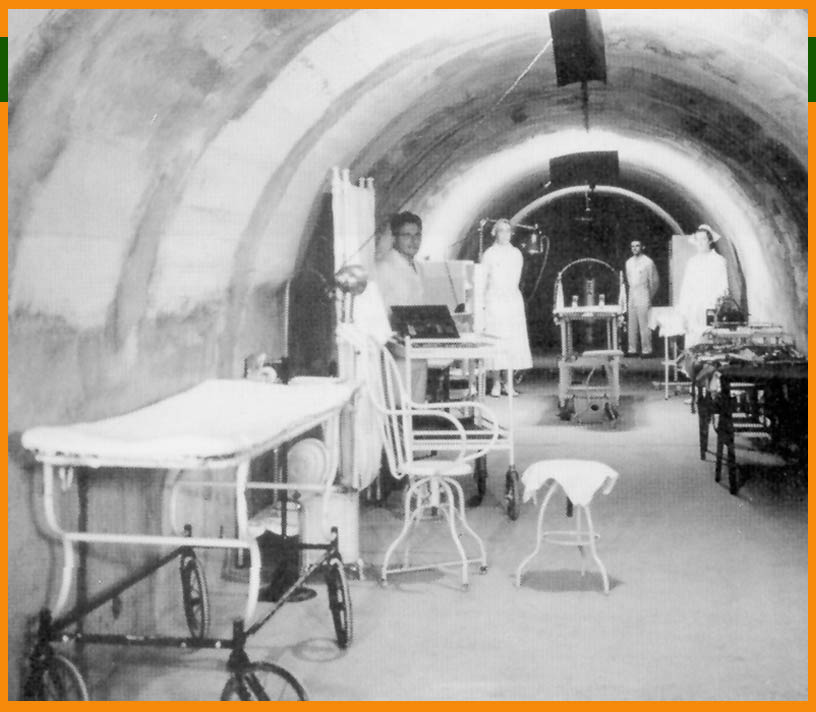

The hospital in the tunnel

Corporal Rush arrived in The Philippines sometime before Japan attacked the islands in December 1941. He was part of the Fort Mills’ Medical Detachment on Corregidor island in Manila Bay.

As an enlisted man, Corporal Rush was likely part of a medical unit. He would have taken initial care of sick and wounded men in his unit’s assigned zone, helped ensure sanitary conditions, and more.

Rush probably time in the fort’s underground hospital inside the Malinta Hill tunnels. Equipped with running water, showers, and flushing toilets, the tunnel hospital eventually had 1,000 beds.

The first 3 months of 1942 were relatively quiet on Corregidor as the Japanese focused their attention on the Bataan Peninsula, just across Manila Bay. Still, the Japanese blockade prevented food and supplies from reaching Corporal Rush and his fellow servicemen. Sanitation, hunger, and diseases became problems the Medical Department had a harder and harder time solving.

After Bataan fell on April 9, 1942, Japan set their sights on Corregidor. Daily bombings became the norm. The tunnel hospital’s beds quickly filled with sick and wounded servicemen.

And then Japanese forces landed on May 6, 1942. Corporal Benjamin Rush was a Prisoner of War.

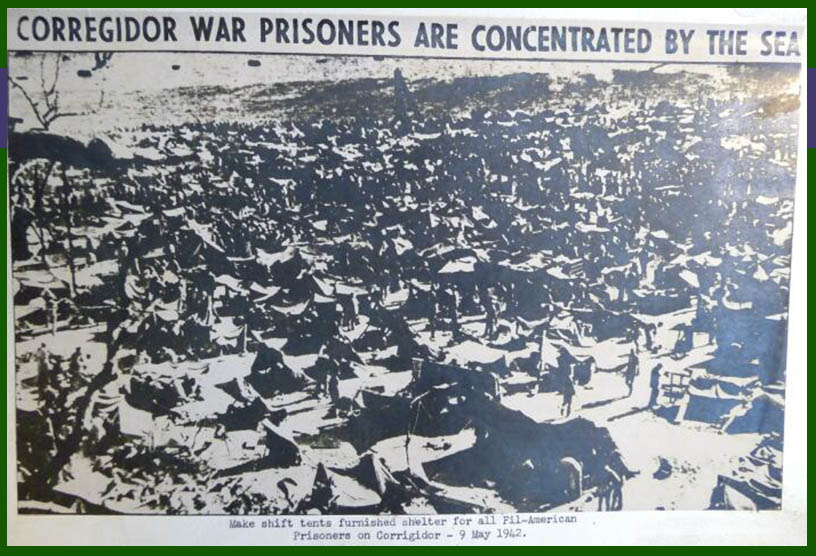

Prisoner life

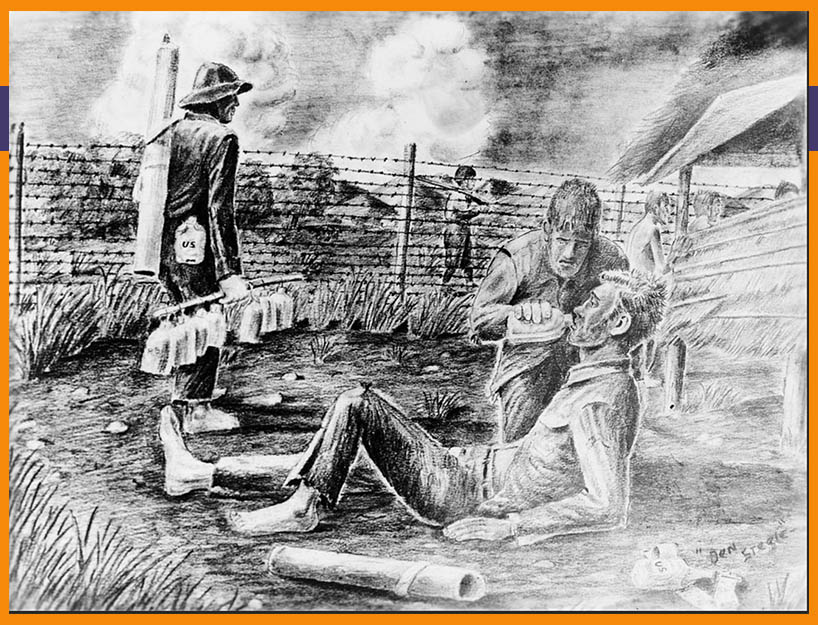

As a POW, Corporal Rush likely joined the other 10,000 American and Filipino POWs at their first camp — at the 92nd Army Garage on Corregidor’s south coast. This hot, oven-like strip of beach with no shelter and little running water was their home for several weeks. POWs using tarps and other scavenged materials to created shelter from the scorching sun and torrential rains.

On May 23, 1942, Rush and his comrades boarded Japanese transport ships and sailed across the bay to Manila. Here their Japanese captors paraded them through Manila’s streets — a show of might to the Filipino population — to Bilibid Prison, where the POWs again erected their tarp tents and scavenged what food they could.

The next day, Corporal Rush endured a 70-mile trip to Cabanatuan City in an overcrowded, stifling, standing-room-only, enclosed boxcar. Then came a 16-mile march to Cabanatuan POW Camp.

Corporal Benjamin Rush spent several years at the Cabanatuan POW Camps, although the exact dates he was there aren’t known.

The Cabanatuan “hospital”

The first few months at Cabanatuan would have been especially busy for Rush. The camp had no official hospital facility — but massive amounts of sick and dying men — when they first arrived at Cabanatuan. In addition, the camp’s medical department lacked facilities, medicines, food, and sanitary supplies to treat the malaria, dysentery, and malnutrition running rampant among the POWs.

More than 1,500 POWs died during the first 3 months at Cabanatuan (June-August 1942). Those beyond help went to the Zero Ward — a barrack where the sickest POWs went to die. They laid, naked, on the bare floor. Medical staff attempted to keep the ward clean with make-shift brooms. They tried to keep the dying men as sanitary as possible. But not even the Japanese doctors would enter the Zero Ward.

All of this, Corporal Rush would have seen and been part of.

As fall came, some medications arrived. Sanitary conditions improved, somewhat slightly, as the POWs engineered septic and drainage systems and cpmverted a barracks into a camp hospital. The death rates slowed.

Work Details

In early 1943, the Japanese ordered most medical staff out of the make-shift camp hospital and into the labor details with the other 6,000+ camp POWs. Since he was an enlisted member of the medical department, it’s likely the Corporal Rush worked these labor details rather than in the camp hospital.

With his fellow medical staff, he probably worked on the prison farm, hefted an ax on the wood-cutting detail, used a pick and shovel to create an airstrip near camp, carried heavy loads of vegetables from the prison garden to camp, or transported buckets of feces from camp latrines for the prison farm’s fertilizer needs.

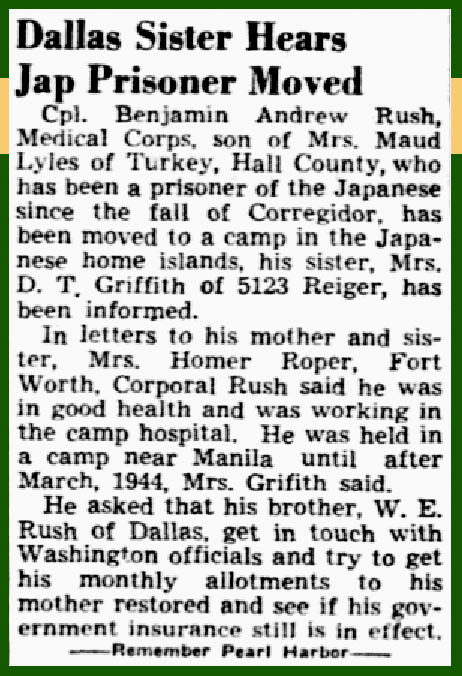

The news back in Dallas

Back in Dallas, Corporal Rush’s sister didn’t have any news about her brother until July 1942 — 2 months after Rush became a POW. The news came from the War Department. Corporal Benjamin Rush was Missing in Action.

A similar note followed a year later in July 1943 — Benjamin Rush was still MIA.

Did MIA mean alive? Were they looking for him?

“Sometimes you can get awfully low worrying over the fate of your loved ones,” Mrs. Griffith said. She’d exhausted all resources trying to get any word of her brother’s status.

Then a post card arrived in August 1943. This time from the Japanese army, informing her that Benjamin was a POW in The Philippines. Joy! Relief! “Never give up hope,” she advised others with missing soldiers.

After that, the family had at least some correspondence with him, although quite slow.

In letters, Corporal Rush told his family that he remained at Cabanatuan until at least March 1944. And in June 1945, the Rush family learned that Benjamin was in a POW camp in Japan itself.

“The worst experience of all”: Fukuoka’s Pine Tree Camp

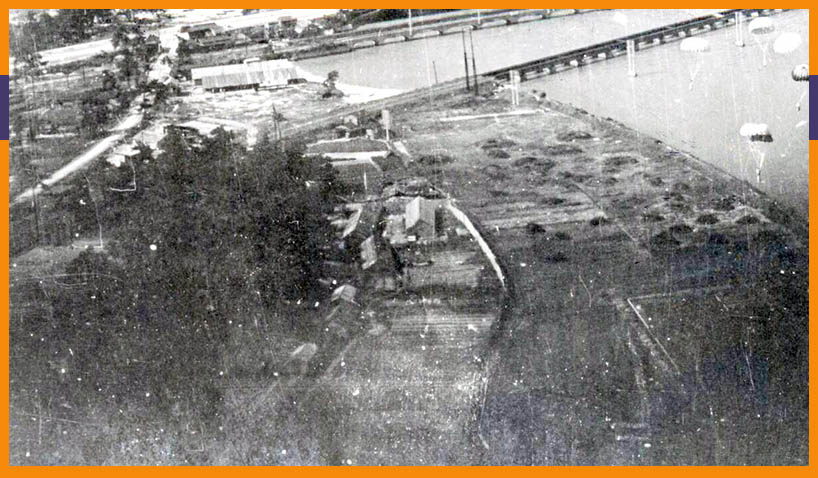

The Japanese sent Corporal Rush to the Fukuoka #1 POW camp. The prisoners called it the “Pine Tree Camp.” And one described it as “the worst experience of all.”

He and fellow POWs lived in barracks with dirt floors, where they slept on raised wooden platforms. Their diet was mainly rice, with some vegetables and vary rarely meat.

And where heat and humidity had been the norm in The Philippines, the weather was vastly different at the Pine Tree Camp. Especially during the winter.

Corporal Rush worked at the camp’s “hospital,” which — unsurprisingly — lacked medicine and facilities to help sick and wounded men. Many of the men here survived Japanese hell ships, which exacerbated their already sick and malnourished conditions. The guards were not sympathetic to sick men, making them continue working, cutting their rations, and hitting and kicking them when they didn’t keep up.

Corporal Rush would have tended these patients.

The camp commander was a brutal man, as were his guards, 2 of whom the POWs nicknamed “Bulldog” and “The Beast” because of their especially brutal beatings. The prisoners endured constant roll calls, inspections, and punishment for minor “crimes.”

In September 1945, some 40 months after his capture on Corregidor, American forces liberated Benjamin Rush from the Pine Tree Camp.

He was going home. He’d kept that promise to his sister.

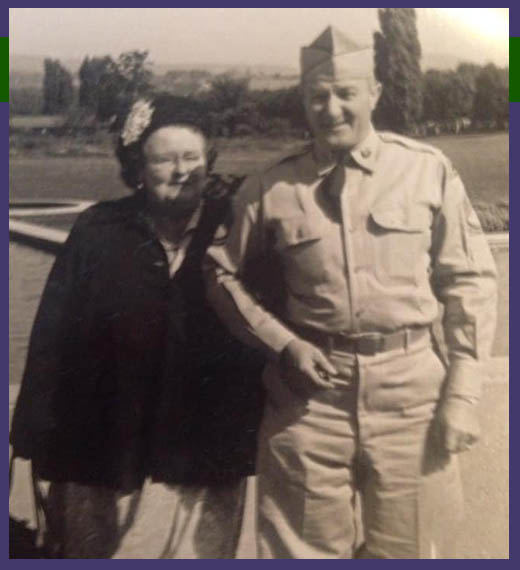

A show-and-tell grandpa

Benjamin Rush remained in the Army post-war, eventually rising to the rank of Sergeant First Class (meaning he was a non-commissioned officer) before retiring in the 1960s.

On March 1, 1946, Benjamin married Viola Hughes, a widow with 3 children. And although he had no children of his own, Benjamin wholeheartedly became part of Viola’s family.

“I used to take him to school for show and tell!” recalls granddaughter Cleta McDow. “Benjamin is the only grandpa we knew.”

As a married military couple, they lived at bases in North Carolina, Germany, Montana, and Georgia before settling in Seaside, California, in 1955. Viola died in August 1961, and Benjamin married Violet Fowler the next year. That marriage lasted 7 years until their divorce in October 1967.

Benjamin Andrew Rush died March 5, 1976, in Monterrey California. He rests at Mission Memorial Park in Seaside.

Read Next

Sources

- Andy Rush, Precinct 1, Swisher, Texas, 1930 United States Federal Census, database online, Ancestry.com, Original data: United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1930. T626, 2,667 rolls, accessed 10 June 2020.

- Benjamin Andrew Rush Jr, 1940 US Census, Bexar, Texas, database online, Ancestry.com, original data: United States of America, Bureau of the Census, Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1940, T627, 4,643 rolls, accessed 15 May 2020.

- Ben A Rush family, Justice Precinct 7, Swisher, Texas, 1920 United States Federal Census, database online, Ancestry.com, Images reproduced by FamilySearch, Original data: Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920, (NARA microfilm publication T625, 2076 rolls), Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C., accessed 15 May 2020.

- Benjamin A Rush family, 1910 United States Federal Census, Justice Precinct 7, Swisher, Texas, database online, Ancestry.com, original data: Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910 (NARA microfilm publication T624, 1,178 rolls), Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29, National Archives, Washington, D.C., accessed 15 May 2020.

- Benjamin A Rush. Ancestry.com. California, Death Index, 1940-1997 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2000. Original data: State of California. California Death Index, 1940-1997. Sacramento, CA, USA: State of California Department of Health Services, Center for Health Statistics. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- Benjamin A Rush and Violet J Fowler, Ancestry.com. California, Divorce Index, 1966-1984 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007. Original data: State of California. California Divorce Index, 1966-1984. Microfiche. Center for Health Statistics, California Department of Health Services, Sacramento, California. Accessed May 15, 2020.

- Benjamin A Rush and Violet J Hale, Ancestry.com. California, Marriage Index, 1960-1985 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007. Original data: State of California. California Marriage Index, 1960-1985. Microfiche. Center for Health Statistics, California Department of Health Services, Sacramento, California. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- Benjamin A Rush, U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2005. Original data: National Archives and Records Administration. Electronic Army Serial Number Merged File, 1938-1946 [Archival Database]; ARC: 1263923. World War II Army Enlistment Records; Records of the National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 64; National Archives at College Park. College Park, Maryland, U.S.A. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- Benjamin A Rush, Ancestry.com. World War II Prisoners of War, 1941-1946 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2005. Original data: National Archives and Records Administration. World War II Prisoners of War Data File [Archival Database]; Records of World War II Prisoners of War, 1942-1947; Records of the Office of the Provost Marshal General, Record Group 389; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. Accessed 4 May 2020.

- Benjamin Andrew Rush, Ancestry.com. Texas, Birth Certificates, 1903-1932 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2013. Original data: Texas Department of State Health Services. Texas Birth Certificates, 1903–1932. iArchives, Orem, Utah. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- Benjamin Andrew Rush Sr, obituary, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Fort Worth, Texas, 25 Apr 1928, page 9, Newspapers.com, accessed 12 May 2020.

- Benjamin Rush, U.S., Department of Veterans Affairs BIRLS Death File, 1850-2010, database online, Ancestry.com, Original data: Beneficiary Identification Records Locator Subsystem (BIRLS) Death File. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, accessed 15 May 2020.

- Cleta McDow, Facebook conversations with Anastasia Harman, May 2020, archived on Facebook.

- Col. Wibb E Cooper, “General Review of the Entire Period”, “The Medical Service on Corregidor,” and “Fukuoka,” Medical Department Activities in The Philippines from 1941 to 6 May 1942, and Inclusing Medical Activities in Japanese Prisoner of War Camps, Office of the Surgeon General, 23 April 1946, found online at http://mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/philippines/cooper_med_report.html#GENERAL_REVIEW, accessed 10 June 2020.

- “Dallas Sister Hears Jap Prisoner Moved,” Dallas Morning News, 8 June 1945, page 12, found on Newspapers.com, accessed 15 May 2020.

- Mrs. Viola Rush obituary, Lawton Constitution, Lawton, Oklahoma, 30 August 1961, page 14, found on Ancestry.com, accessed 10 June 2020.

- “Fightin’ Men: News of Texans in US Service,” Dallas Morning News, 6 April 1942, page 6, found on Newspapers.com, accessed 15 May 2020.

- “Twice Told Her Brother Lost, Woman Learns He’s Prisoner,” Dallas Morning News, 30 August 1943, page 6, found on Newspapers.com, accessed 15 May 2020.

- “The WW2 Medical Detachment Infantry Regiment,” US WW2 Medical Research Centre, found online at https://www.med-dept.com/articles/the-ww2-medical-detachment-infantry-regiment/, accessed 10 June 2020.

Images

- Image 1. Corporal Rush portrait. “Twice Told Her Brother Lost, Woman Learns He’s Prisoner,” Dallas Morning News, 30 August 1943, page 6, found on Newspapers.com, accessed 15 May 2020.

- Image 2. Tule Canyon. “Briscoe County Butte in Tule Canyon, Texas,” taken by Leaflet, June 2004, Wikimedia, found online at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Briscoe_County_Butte_in_Tule_Canyon,_Texas.jpg.

- Image 3. Malinta Tunnel hospital. US Army Signal Corps, public domain, found online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Angels_of_Bataan#/media/File:Malinta_Tunnel_Hospital.jpg, accessed 1 June 2019.

- Image 4. Army 92nd Garage. POW tents at the 92nd Garage. Found online at “Report of American Prisoners of War Interred by the Japanese in The Philippines, prepared November 1945, http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/philippines/pows_in_pi-OPMG_report.html, accessed 6 Aug 2019.

- Image 5. POWs at Cabanatuan drawing. By former POW Ben Steele.

- Image 6. Dallas Morning News article. “Dallas Sister Hears Jap Prisoner Moved,” Dallas Morning News, 8 June 1945, page 12, found on Newspapers.com, accessed 15 May 2020.

- Image 7. Map. Created by Anastasia Harman, October 2019.

- Image 8. Pine Tree Camp. “Prisoner of War Camp #1: Fukuoka, Japan,” found online at http://mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/fukuoka/fuk_01_fukuoka/fukuoka_01/Page01.htm#Locations, accessed 11 July 2019.

- Image 9. Benjamin and Viola. Picture courtesy Cleta McDow. Shared with Anastasia Harman, May 2020.

- Image 10. Benjamin’s grave marker. Taken by O. Morgan, Benjamin Andrew Rush memorial, Find A Grave, found online at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/190059999, accessed 11 June 2020.

This is amazing

I am Ben’s oldest granddaughter Donna. I loved him so much. I didn’t know much of this. I lived with him and my grandma, Viola. He never talked about any of this. He was a wonderful man.