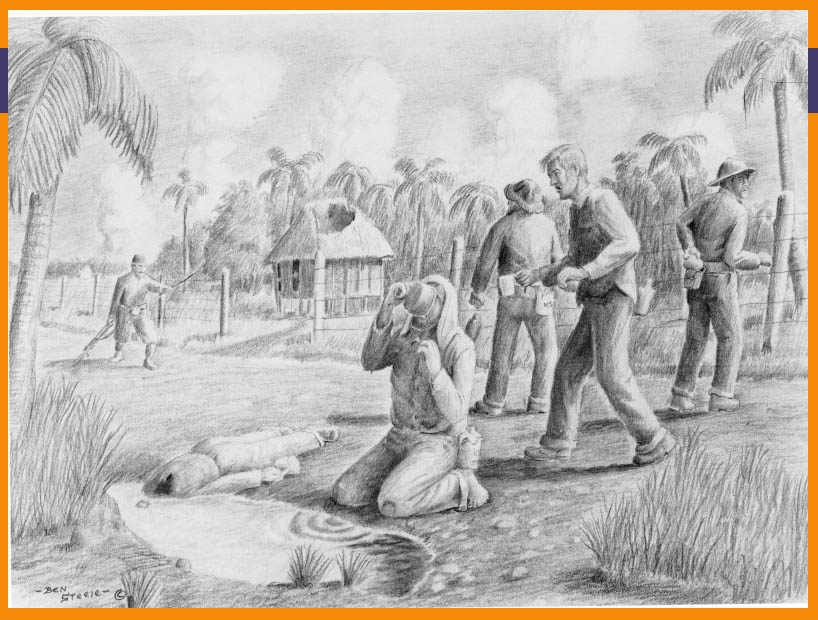

This post is part 8 of Alma Salm’s memoir of being a POW in The Philippines during WW2. You can read from the beginning here. Also, this post contains some mildly graphic descriptions of war-time treatment of POWs during an event similar to the Bataan Death March.

It was just dawn when we began the last of our weary trek to prison camp Number Three, twenty-one kilometers away.

As we marched out of the city to the eastward, the sun had just risen above the mountains.

The path of our march led directly into the sun, and it wasn’t long before we felt the effects of old sol who was radiating his blasts of heat from the “old stand.” Soon we were perspiring freely as one does so quickly and so easily in the humid tropics after little physical exertion.

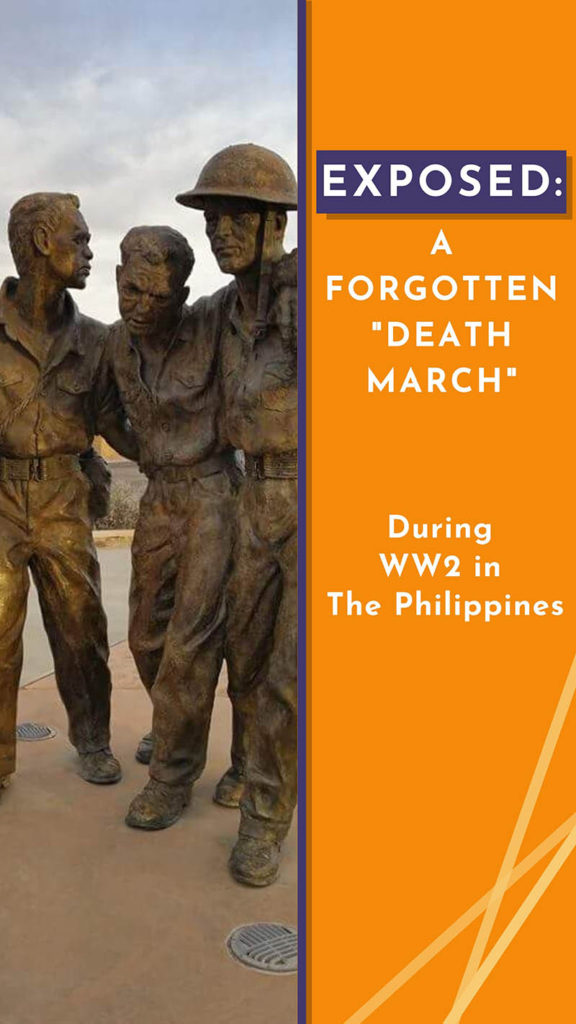

After a couple of kilometers we felt the effort of walking and our light packs of belongings hung heavily on us indeed. As before, some of the weaker men commenced to fall by the wayside but were brutally prodded to their feet by bayonets fixed on their rifles.

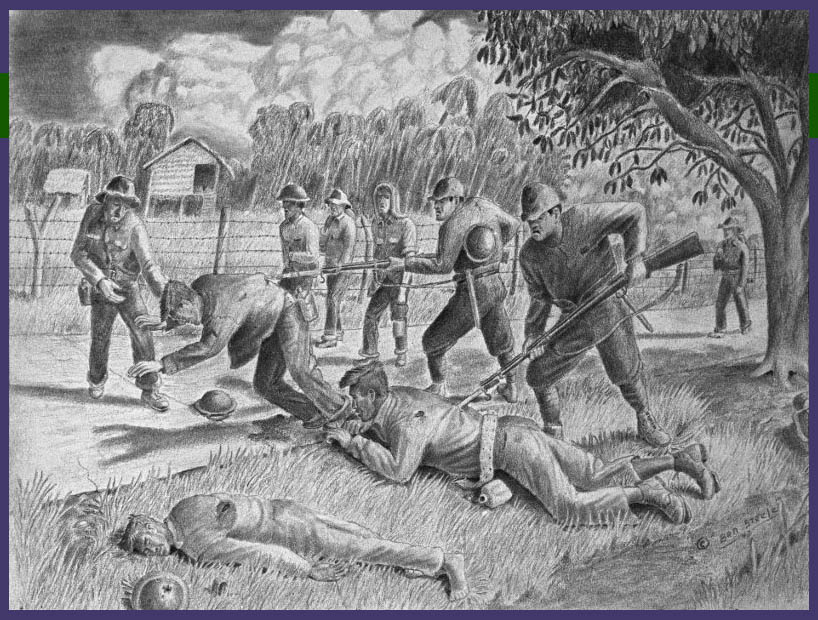

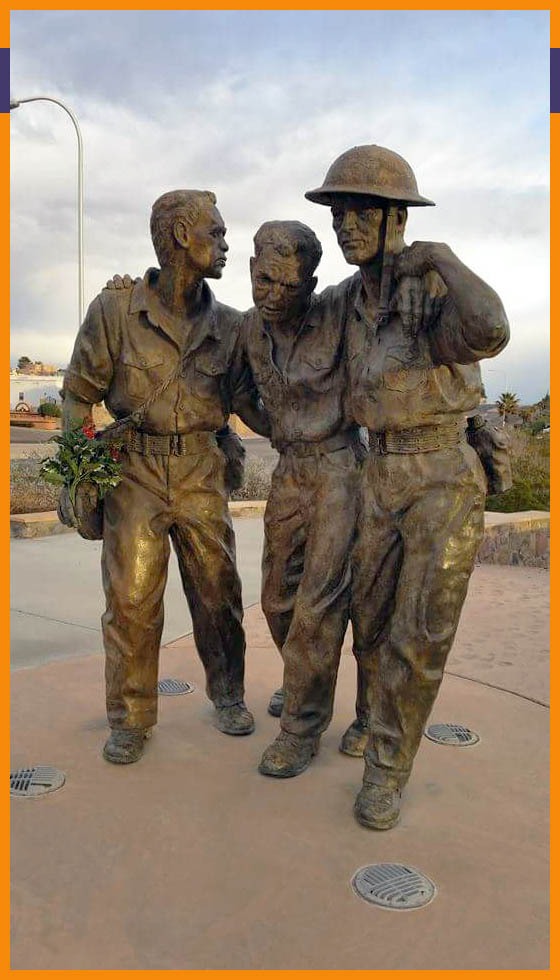

We were fearful as to what [the Japanese] would do if our weaker fallen comrades did not get up again because past practices of the Japs were to bayonet or shoot to death those who could not survive to continue the march (as [the Japanese] had so ruthlessly done to our predecessors on the “Bataan Death March” some seven weeks before).

There were those who were footsore, weak, and suffering from malarial fever who were oblivious as to what was going on about them as they tottered along.

Thirst — A death march killer

After walking sever kilometers [about 4.33 miles], the column was ordered to halt for a change of guards. We utilized this stoppage by dropping alongside the road for a rest. By this time we had perspired so freely since the march began that our clothes were drenched and steaming hot.

We gazed about for a little drinking water to fill our canteens.

All we could find was a small ditch alongside the road that looked like it contained stagnant water and which was used by the native carabao (water buffalo) in which to wallow. In addition we found a small, shallow well out in an open rice field. But the water therein appeared to the same as that in the ditch reaching there as seepage.

We were cognizant of the fact that drinking this apparently polluted water without boiling under these conditions might cause dangerous infection to us especially that of the widely prevalent dysentery in these areas.

But it was indispensable that we have water to quench parched throats.

Fortunately some of us still had a ten percent solution of iodine in alcohol and a tiny tin of chlorine. These we mixed freely with the water and let stand for about fifteen minutes before drinking it. Of course, it tasted bitter, like some poison, after being so doctored, and it was very unpalatable but it gave our wrung-dry systems a little badly needed moisture.

A disheartening sight

Just a stone’s throw from us was a large compound containing many large and small empty thatched-roof nipa buildings and which later on became Prison Camp Number One.

We thought our journey was ended but soon learned we were to continue another fifteen kilometers [9.3 miles] to Camp Number Three. This disheartened all of us considerably and just about took all the “starch” out of us.

Stabbing sick men too weak to continue marching

Very shortly the new Jap guards barked and screamed their orders with vehemence to start moving again and every step was painful with raw open blisters now on our feet to add to our other physical deficiencies.

More men collapsed by the wayside.

Occasionally a Jap guard would let one lie when it filtered through his sluggish brain that the man was indeed too sick to stand on his feet, but others almost as bad who fell out were treated badly because the particular guard thought they were merely tired. These he would continually prod with his bayonet, and they would rise again with the help of their comrades to stumble along for a short distance only to drop again shortly afterward.

The process in some cases was repeated again and again. At times the guard drew blood when jabbing his bayonet a little too hard. It was pitiful to see, and our feelings alternated with sympathy for the victims and resentment toward our Jap guards, but we knew we could do almost nothing to alleviate the suffering.

Malaria — another death march killer

There was not a breath of air stirring.

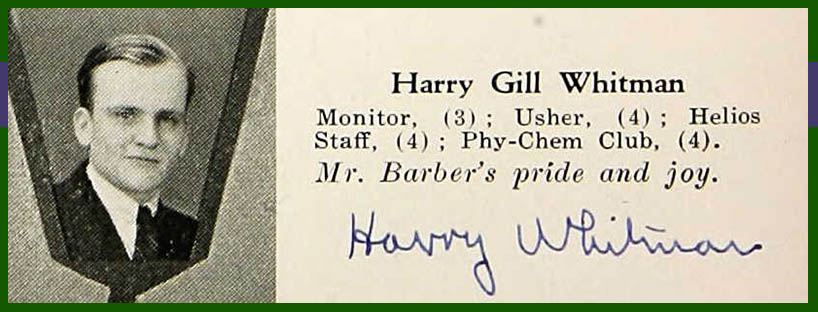

Marching in the direct rays of the sun which hung like a hot molten ball in the cloudless sky, Ensign Whitman beside me had another attack of malaria. His fever rose rapidly as it invariably does when this happens. He likewise could hardly stand on his feet.

I attempted to carry his belonging again in addition to my own so he would not lose them.

My companion began to waver and finally to lean on me.

With each step, the jungle fever sapped more of his waning energy. He was a large husky fellow, a former champion swimmer, and sustaining his weight plus carrying two packs was a little more than I could maneuver in my exhausted condition. But at least, I thought, I didn’t have five degrees of fever as he had walking along in that torrid heat.

I tried to explain to a very surly guard we were unfortunate to have flanking us, that my companion was too sick to walk further. I said “malaria” and touched Whitman’s forehead to indicate fever. I didn’t know anything about the Japanese language then as I did later. Perhaps if I had known how to say gaitai (meaning “sick in the head”) it might have made a little impression.

The guard just scowled, looked at me fiercely, and very menacingly pointed his bayonet at me in answer.

Painful Japanese-language lessons

We were both on the verge of a black out. Realizing something had to be done to ease the load, I reluctantly discarded our baggage containing all our blankets and all of Harry’s worldly belongings along the side of the dusty road.

In those belongings, we owned between us about a dozen bananas and mangoes — precious food which we lost. That indeed was sorely grieved us.

Finally my companion just slithered from me as I was unable to support him any longer. The guard attempted to make him get up with the prick of the bayonet, and I was fearful the treatment might result in something less playful.

I mustered all my remaining strength, and with the help of another man, himself in difficulties, we lifted [Whitman] up. In a semi-conscious state, we half dragged him for about a block.

The guard pointed forward with his gun and said, “house-o.”

When he said, ”Hous-o” we thought he meant a small nipa hut a short distance away in a rice paddy and assumed it to be, perhaps, a First Aid Station.

I was wrong in my conclusions for as we broke from the column and started down the little path toward the bahay, it was only too evident we did the wrong thing.

The Jap guard came screaming at us. He was very wrathful as he approached. With bayonet fixed to his rifle he made a lunge at us. We both felt the impact of cold steel. As I felt its meaning prick, I half pulled, half dragged my companion and myself back in the column again being banged intermittently with the butt of his weapon.

A comrade falls on this death march

By the will of God we traversed another two hundred yards, but each new step became a distinct and contemplated torture for us. Then, at the foot of a hill, our strength came to an end.

I arose and tried to pull him up. It was no use. Whitman had slipped into merciful unconsciousness.

At last the unfeeling guard let him lie in the deep grass bordering the road and planted a tall spiked bamboo stick to which was attached a piece of white muslin painted with Jap Kanji characters. indicating that a recumbent form lay at its base.

So many others in the column near us were weak or half sick from malaria or dysentery, and it was all they could do to stand on their own feet, so help could not be expected from them.

I felt pretty rotten about leaving Harry there, but I knew a truck would pick him up eventually.

He was a splendid fellow, and I enjoyed my associations with him thru the months at Camp Number Three and on the Nichols Air Field detail. His hobby was “small” boat building, and I sincerely hope he may return safely and enjoy the fulfillment of his plans of which he spoke to me often.

How a smile almost led to certain death

Later that day when a truck brought the casuals of that march to Camp Number Three, Whitman told me that after he came to his senses, he looked up and saw a Jap guard nearby who was attracted to him when he began to stir.

Harry said he looked up with a pleasant look and slight smile on his face. He was naturally a good-natured individual.

The guard mistook this as an indication that he had been playing opossum and apparently thought a person who is sick is certainly not able to smile about it. Whatever passed thru that Oriental mind, Whitman told me that the Nip was just about to slash him with that bayonet he held poised above him and sensing a crisis tapped his head whereupon the guard realized he was a sick man.

It was a tense moment. That well-intentioned smile was almost his nemesis.

Continuing on alone

I half remember slowly inching toward the crest of the rise. After we ascended we could see eastward far over the countryside to the definite dividing point between plains and the mountainous regions.

For many kilometers this hill and bench country stretched away on three sides heavy with tall cogan grass, brush, and forestation. Beyond rose the high mountain ranges of eastern Luzon and beyond that the Pacific Ocean.

This mountainioun area is the home of the Ifagaos, Colingas, and other pagan mountain tribes living in what the cartographers indicate on their maps as “Unexplored Territory.” This vast region is heavy in tree growth, interlacing vines, and an inpenetrable jungle. Few explorers have penetrated here and know little about those extensive virgin regions or the tribes who inhabit them. The aborigines of this archepelago are not related to the Filipinos who emigrated to this land centuries before from the Malayan Peninsula.

Blackout – Alma Salm succumbs to the march

Upon attaining the top of the knoll, guards were changed and fifteen minutes’ rest period was proclaimed. At this point, I suffered a complete blackout from heat prostration.

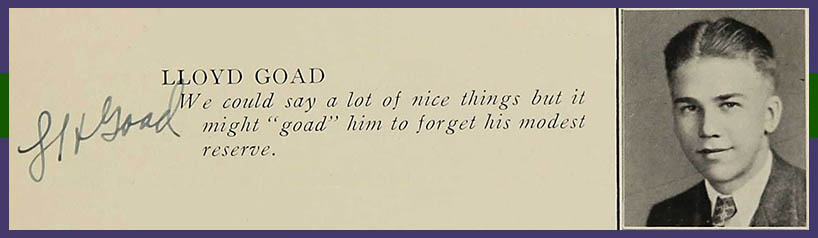

I recovered consciousness with Captain [Lloyd H.] Goad, Army Medical Officer, kneeling by my side. He had a small pocket medical kit for personal use and revived me with some preparation he administered.

The column had disappeared up the dusty road and were out of sight. He had been permitted by one of the new guards to remain with me.

About a half an hour later, a truck came along [and picked us up]. I was relieved to find Whitman among several casuals aboard.

Death march ends; camp life begins

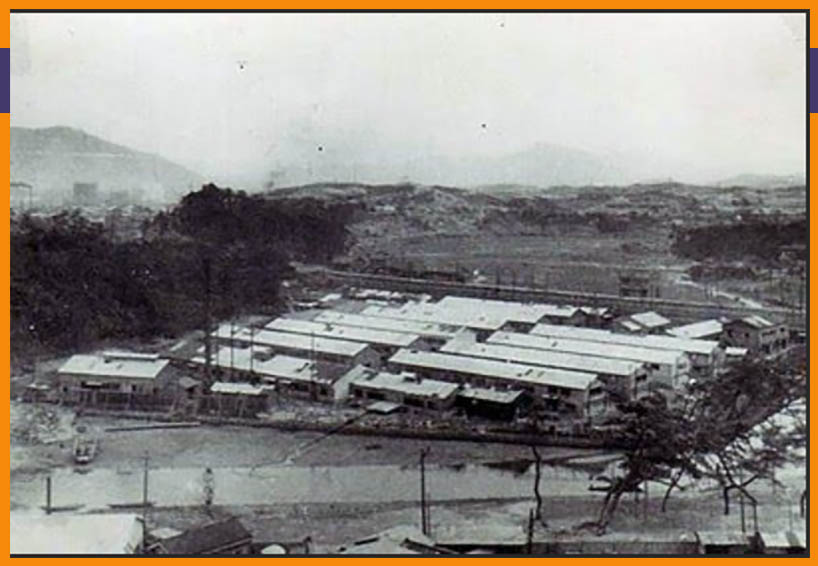

This truck passed the marching brown column [of POWs] and dumped us off at Prison Camp Number Three, where we sank on the ground under a small tree.

A U.S. marine lying on his back beside me shoved his hat off his face and — glancing toward the Jap Army flag, its red ball blazing from a white field, flying from the sequestered Jap area across the road from us — blurted out, “Hell, I never dreamed when I came out here for service under the ‘Stars and Stripes’ I’d ever be doing my cruise under the ‘Fiery Soul of Japan.’”

Yes this was it.

How long were we to serve under this banner of [Japan’s Emperor] Hirohito, “the August Son of Heaven,” before our tanks and guns and fighting Americans would arrive, I thought as I watched a detachment of our men who had proceeded us in to camp the day previous and were now erecting six-foot-high prison walls of barb wire to lock us in from the outside world.

Read Next

Images

- Image 1. Cabanatuan scenery. Image from Adobe Stock photos.

- Image 2. Carabao in rice field. Image from Adobe Stock photos.

- Image 3. Drinking from mud puddle. Drawing by Ben Steele, from Tragedy of Bataan, found online at http://www.tragedyofbataan.com/bsteele/, accessed 16 October 2019.

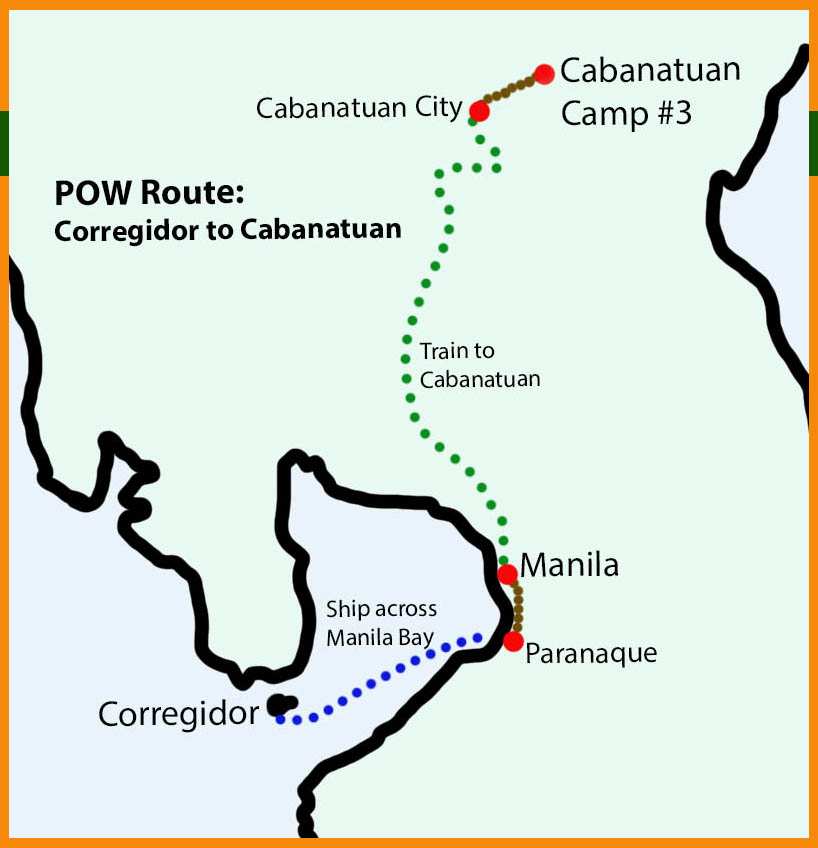

- Image 4. Map of march route. Created by Anastasia Harman.

- Image 5. Bayonetting a straggler. Drawing by Ben Steele, from Tragedy of Bataan, found online at http://www.tragedyofbataan.com/bsteele/, accessed 16 October 2019.

- Image 6. Harry Whitman’s yearbook photo. Harry Whitman in Central High School Yearbook, 1934, Grand Rapids, Michigan, Ancestry.com. U.S., School Yearbooks, 1900-1999 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010, accessed 15 October 2019.

- Image 7. Bataan Death March Memorial Statue. Taken by Kris Punke, Wikimedia Commons, found online at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bataan_Death_March_Memorial_Las_Cruces_NM.jpg, accessed 16 October 2019.

- Image 8. Nipa in The Philippines. Image from Adobe Stock photos.

- Image 9. Philippine countryside. Image from Adobe Stock photos.

- Image 10. Lloyd H. Goad yearbook photo. Lloyd Goad in Mann High School Yearbook, 1931, Gary, Indiana., Ancestry.com. U.S., School Yearbooks, 1900-1999 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010, accessed 16 October 2019.

- Image 11. Cabanatuan POW Camp. Pinned by Tony Austria, Pinterest, found online at https://www.pinterest.com/pin/535365474427503687/?lp=true, accessed 16 October 2019.

![Exposed: A Lesser-Known WW2 “Death March” [Memoir #8]](https://www.anastasiaharman.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Bataan-Death-March-Memorial-Statue-367x590.jpg)