This is the sixth excerpt from Alma Salm’s POW memoir. It picks up where the fourth excerpt ends — with the POWs leaving Corregidor island. The fifth excerpt was Salm’s flashback to his pre-capture time on the USS Canopus.

Fortunately we who were on Corregidor escaped the infamous “Bataan Death March.”

However we soon learned the Japs were not without their plans for us also.

1. Japanese ships dumped the POWs in the water

Instead of warping our ships alongside the piers of Manila they headed five miles south and anchored two miles off shore from the Manila suburb of Paranaque. We disembarked into small troop landing barges used principally in amphibious operations.

When we were about two to three hundred feet away from the beach, we were ordered to jump into the bay. The gunnels of the boats were up to our breasts so we had to disembark out over the lowered ramp in the stern.

There was only room for about four or five to leap off at one time, and as the barge began to drift seaward caused with the motion of disembarking men, the last occupants (and I was one of them) who jumped overboard were in water nearly six feet deep. That just about left the top of my head out of the water.

Most belongings became wet, although, with good fortune, one in the shallower water could hold their bag of belongings above their heads as they descended into the brine. It was a particular hardship for those who were sick among us, but the heartless Jap took no cognizance of that.

The bay bottom here was muddy and sandy.

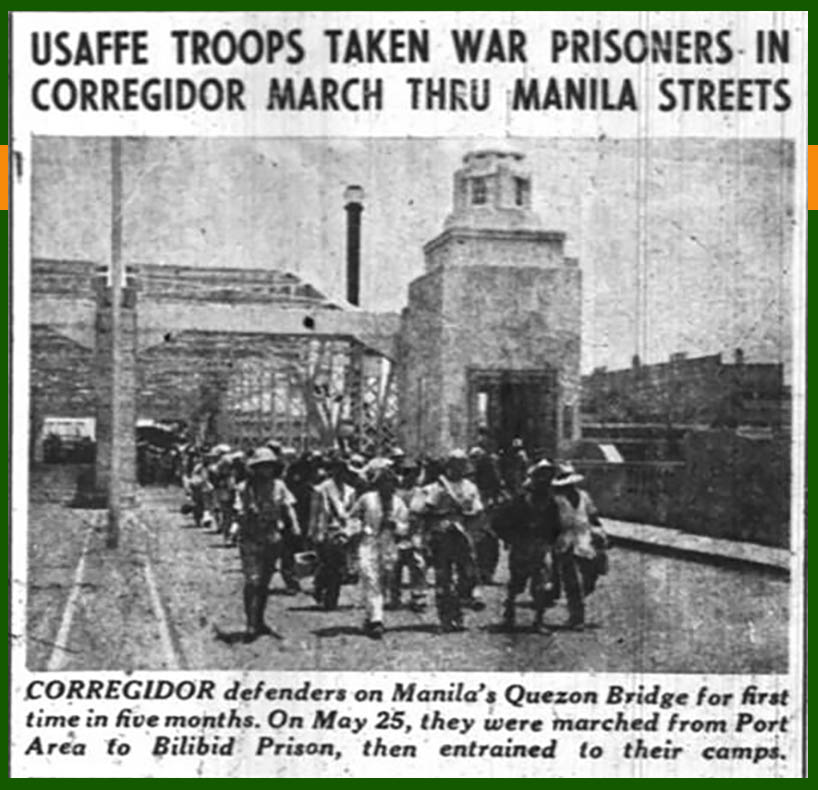

2. They paraded the dirty, exhausted, starving POWs through Manila

After all emerged from the waters of Manila Bay everyone was immediately formed into columns. We were a weary, hungry, bedraggled lot of humanity; unshaven, unkept, and dirty. Just precisely as the Nips wanted us, as part of a diabolical Japanese plan.

This was to be a parade of humiliation for the beaten white race.

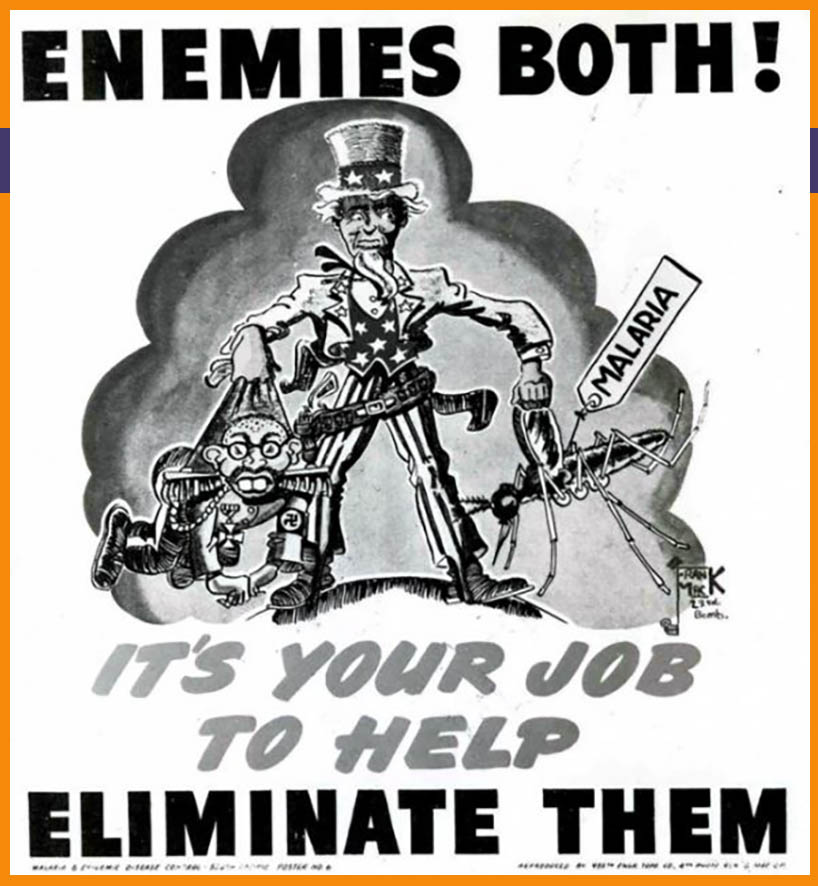

It was now about high noon, and we almost wilted in the torrid heat. An ideal condition to cause those previously infected to have the dreaded and recurrent malaria which happened in numerous cases during that never-to-be-forgotten march.

In our sand-filled soggy shoes, we began our long hot trek up the famous Dewey Boulevard, thru the streets of the city of Manila to the old Spanish Bilibid Prison about eight miles away.

During the period from early morning of the day before when we “broke camp” at the 92d Garage until now the Japs gave us no food or water whatsoever, although there was a little tepid water available on board the ship via an old spigot. This combined with little sleep the two previous nights, we were additionally weakened and very tired.

3. Japan officials lined Manila’s streets to gloat over the beaten enemy

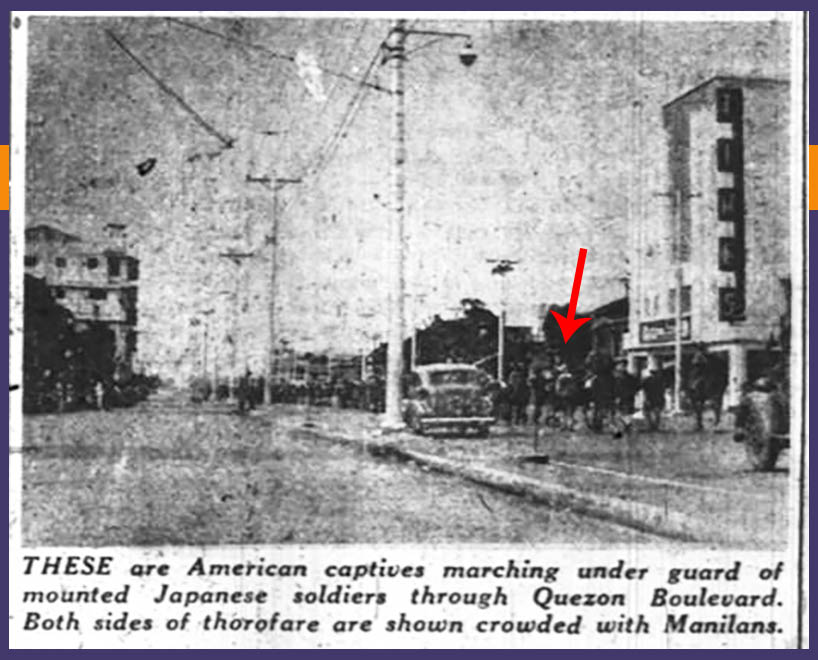

As the long column moved on, we were flanked at intervals by gloating Japanese guards on horseback. This spectacle was enjoyed in the manner of a Roman holiday to the Japanese High Command, Army officers, officials, Jap soldiers, and civilians who turned out with pleasant anticipation to view the hated fallen American gladiators.

This parade was to indicate the supreme power and might of the Emperor and Nippon before the Filipino people and to show and impress them with the beaten Americans in utter and ignominious defeat and loss of prestige (“loss of face”), in which the Jap places so much pride invoking on his conquered enemy.

4. They ordered Filipinos to watch the POWs march

In their show of arrogance and utter contempt of us, the Japanese expected to convince the Filipinos — who had been ordered to review us — that they were the all-powerful rulers henceforth.

But the Japs misunderstood the Filipino character and his loyalty, for the most part, to the American regime. Japanese control during these five months had not convinced the Filipinos. The liberty he enjoyed under America was now strangely missing. He realized he had lost that, and it soured the Filipino.

As the motley throng of captive American troops were prodded along, many fell, but the Jap guards ruthlessly prodded them to their feet with their bayonets and sabers.

If Japan thought the moral effect of the Filipinos upon seeing us so degraded would be regarded in the manner they anticipated, they were very much mistaken. The understanding and kindly Filipinos did not smile or jeer nor scorn us, but rather they had the look in their eyes and on their countenances of sorrow and sympathy for us.

Many of them openly wept.

Others made the “V” sign with their fingers when the guards were not alert.

We marched by, doing a pretty good job of holding up our heads, and, with pride, I noted it was going to take more than a Jap bayonet to wipe that courageous grin off the American face. In view of our temporary defeat, this was about all we could offer in return for the gallantry of those loyal Filipinos.

We remembered then, and so did the Filipinos now looking upon us, that for every white soldier on the “Bataan Death March,” just seven weeks before, there were about nine Filipino soldiers by his side. And together they all endured the brutal punishment and the lash and venom of the Jap conqueror, and in hundreds of cases endured until death mercifully rescued them.

5. Japan forced malaria-ridden POWs to march

At intervals some of those who suffered with sickness and other afflictions, unable to move further on foot, fell down and remained down.

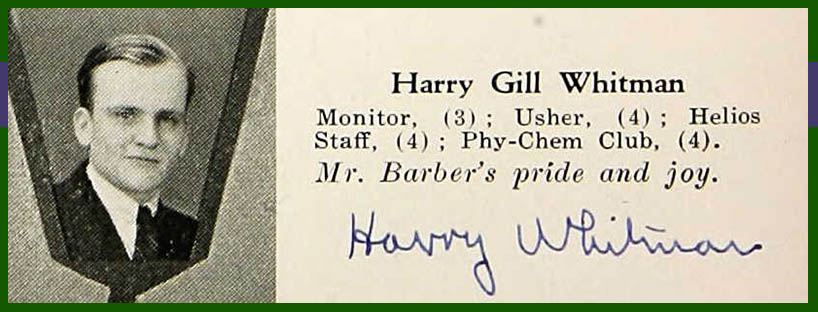

When the column I was marching in neared the heart of the city, Ensign Harry Whitman, USNR, who had been with me on Corregidor and who was my marching buddy, had recurrent malaria induced by exposure to the blazing sun. He began to stumble along, and the only help I could give was the small relief of carrying his burlap sack containing his worldly belongings. This eased things for him a little.

The added burden of carrying his baggage began telling on me, but after another mile he steadily became worse and his fever was so high he was almost delirious.

What to do?

I wasn’t any too sure what the unpredictable Jap guard might do. I wasn’t so valiant I could withstand the jab of a sharp bayonet with calm. Another look at his face however, and I dragged him out of the column beside the road, and quickly covered him with an old rain coat we had salvaged on the “Rock” (as Corregidor was commonly referred to out here). I fed him ten or fifteen grains of quinine, which I had on me.

6. The Japanese offered no first aid for sick POWs

Soon he was shivering violently with the chills that alternate with the fever of a malaria-ridden victim. We both were drenched with perspiration, and I had reached a stage myself where I couldn’t travel much further without a respite after the five miles that lay behind us.

Almost immediately a couple of Japanese guards and a Jap policeman were upon us.

I expected and was prepared for the usual violent physical treatment. However, even the Japanese know the sickening and debilitation effect of malaria through their own experience with it. They felt my tomodachi’s (friend) hot feverish brow as he lay with closed eyes and colorless face and, wonders of wonders, they actually left us alone.

We won a round, and I felt a little relieved for both our sakes. He lay there and by and by opened his eyes.

I spied a Filipino pushing an ice cream wagon. Although I knew the Jap did not permit speech or contact with Filipino civilians I managed to purchase several paper envelopes of mango sherbet. I couldn’t be sure how sanitary the ice was, but it was cold. I fed some to my shipmate who began to recover. The cold sherbet, together with quinine and rest of an hour, helped him.

7. They offered American POWs only minimal, primitive shelter

Later a Jap truck came along and picked us up along with other casuals who had fallen out previously and took us to the entrance of Bilibid Prison. We were soon inside the ancient limestone walled enclosure.

As all the spaces in the old prison buildings were now occupied by our troops who had preceded us, so we lived outside on the ground. Those existing inside had dirty concrete floors to sleep on as there were no accommodations or facilities in those buildings whatsoever.

We decided the only edge they had on us was a roof over their heads during this rainy season.

We had a couple of pieces of Marine Corps canvas shelter halves, and these we rigged over us utilizing the old twelve-foot block limestone wall of the prison death chamber as protection. There was a little patch of green grass here, so the two of us were relatively comfortable with the two blankets we had between us for our mattress and a light blue Navy spread over us.

It rained again that night.

8. They provided little-to-no food for their prisoners

There was fresh water with the inevitable water line, but we didn’t have to wait more than an hour here to have the luxury of an open shower. We washed our odorous bodies, and with a bucket we were able to get fresh water and wash our dirty, stinking clothes.

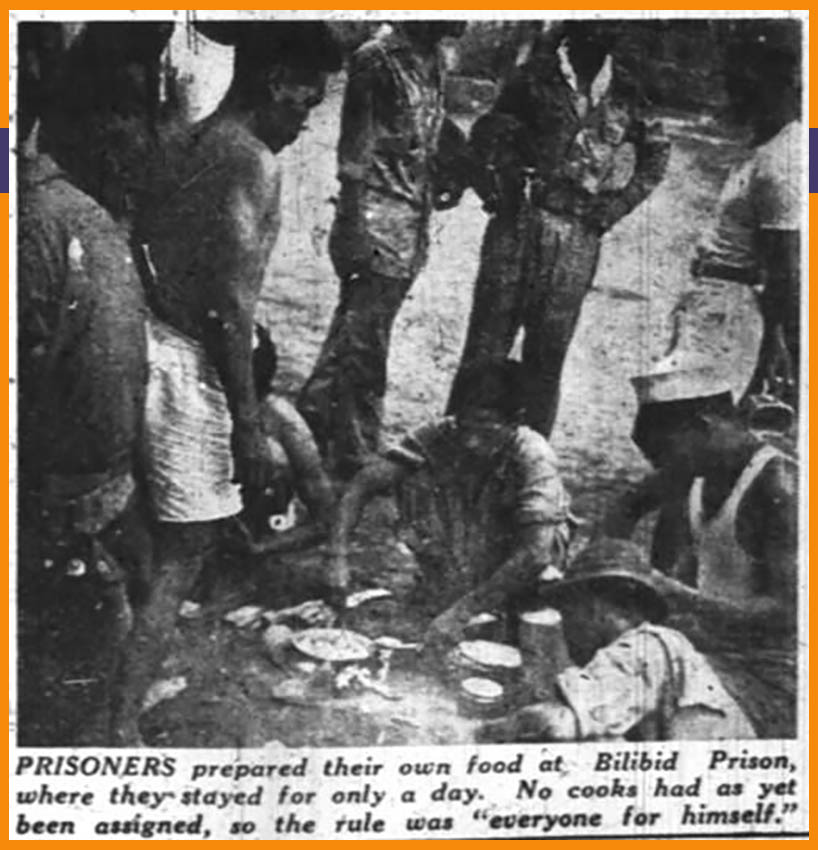

On January 2, 1942, nearly five months previous, when the city of Manila fell to the hordes from the land of the Rising Sun, a number of our forces consisting of hospital personnel were trapped inside the city. Having resided in the Bilibid Prison since then, they had some large-sized cast-iron rice pots and were cooking rice for us on the open ground.

Cooking was done by digging a hole in the ground and fitting in it the blunt conical shape of the bottom of the rice pot.

We were so tired that we were happy just to enjoy the luxury of being able to drop to the ground and rest in the fiery sun.

Could I ask a favor?

The story of the Corregidor POWs and their march thru Manila is being lost to history. Although it’s just one event in an immense world war, it’s something that should be remembered. If you know any one who might be interested in this story, please this post with them. Every share keeps this memory alive. Thank you!

Read Next

Images

- Image 1. “Troops Inspect captured Japanese barge on Guadalcanal 1942,” World War Photos, found online at https://www.worldwarphotos.info/gallery/usa/pacific/guadalcanal/troops-inspect-captured-japanese-barge-on-guadalcanal-1942/, accessed 15 October 2019.

- Image 2: Map of route from Corregidor to Cabanatuan, created by Anastasia Harman.

- Image 3. POWs on Quezon Bridge. From “USAFFE Troops Taken War Prisoners in Corregidor March thru Manila,” The Sunday Tribune, Manila, Philippines, 7 June 1942, page 3, found online at Pinterest, https://www.pinterest.com/pin/120682464999523850/?nic=1, accessed 15 October 2019. Note: This was a Japanese-controlled newspaper.

- Image 4. POWs on Manila street. From “USAFFE Troops Taken War Prisoners in Corregidor March thru Manila,” The Sunday Tribune, Manila, Philippines, 7 June 1942, page 3, found online at Pinterest, https://www.pinterest.com/pin/120682464999523850/?nic=1, accessed 15 October 2019.

- Image 5. Harry Whitman. Harry Whitman in Central High School Yearbook, 1934, Grand Rapids, Michigan, Ancestry.com. U.S., School Yearbooks, 1900-1999 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010, accessed 15 October 2019.

- Image 6. Malaria Poster. “Japs, Japes And Dr Seuss: US Anti-Malaria Warning Posters From World War 2,” Flashback, found online at https://flashbak.com/japs-japes-and-dr-seus-us-anti-malaria-warning-posters-from-world-war-2-36536/, accessed 15 October 2019.

- Image 7. Bilibid Prison. “Bilibid Prison, Manila, Philippines, Feb. 1945,” uploaded by John Tewell, Flickr, found online at https://www.flickr.com/photos/johntewell/6058065261, accessed 15 October 2019.

- Image 8. Cooking at Bilibid Prison. From “USAFFE Troops Taken War Prisoners in Corregidor March thru Manila,” The Sunday Tribune, Manila, Philippines, 7 June 1942, page 3, found online at Pinterest, https://www.pinterest.com/pin/120682464999523850/?nic=1, accessed 15 October 2019.

![8 Horrific Things Japan Did to the Corregidor POWs in Manila [Memoir #6]](https://www.anastasiaharman.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/March-thru-Manila-Featured-image-367x658.jpg)

My father was on Corregidor. He said that he fell within site of Bilibid and never understood why the Japanese guard didn’t kill him. He was also in Cabanatuan before being sent to Camp Hoten in Mukden (now Shenyang), Manchuria. Thanks you for this. I now understand more why Dad hated the beach.

Wow, Susan. What a horrific thing for your father to have gone through and to remember. The Corregidor POWs were already sick and starving when they surrendered. And the marches they went on, although not nearly as long adn horrendous as the Bataan Death March, were disastorous for many of them. Thank you for sharing, I so much appreciate connecting with people who’s family also were on Corregidor and at Cabanatuan. Hoten was no joy ride either. I’m working on a bio for a POW who was released from Hoten at war’s end.

IN case you’re interested, here’s a link to a website with info about that camp: http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/china_hk/mukden/hoten_main.htm

And here’s a website with several picutres from that camp: https://bataanproject.com/hoten-camp-mukden-manchuria/

Thank you again for connecting!

My DAD, Sam Car, was taken at CORREGIDOR.

This was what he wrote later in his life & very hard to read. I found it going through his papers written on yellow legal size paper.

We went to many of the ADB&C REUNIONS in Fontana Dam, NC. I met many of PWs growing up most from Corregidor & then at NATIONAL ADB&C REUNIONS. The one thing my wrote of was when they’d “reach Billibid Prison he had the most good he’d in months on the rock”. I heard similar comments made by others. They were down to half rations supposedly but those ended up being even less then that before being taken PW by the japs.

Edythe, Thank you for sharing this. I am so grateful to connect with you and others whose family are connected to Corregdior. The conditions on Corregidor were so bad by the time the Americans surrendered. I’ve read the same things that you’ve heard in regard to that. The men were sick and starving. So sad. I just looked up your dad in the POW databases I use, and he was definitely captured on Corregdior. The database says he was a Private in the Coast Artillery Corps. He was rescued from the Fukuoka Japan “Pine Tree Camp.” Your father likely also spent time at Cabanatuan Camp with the other Corregdior POWs.

Here’s an article I wrote about a POW captured on Corregidor and who was released from the Pine Tree Camp in Fukuoka, like your father: https://www.anastasiaharman.com/2020/06/12/benjamin-rush/

Thank you again for sharing. I’m grateful for the opportunity to connect with you!

Hello Anastasia…

A decently written article, I’ve been an amateur WW2 historian for 40 years and I lived in the Philippines for 2 years and traveled around Luzon visiting all the WW2 sites. Some atrocities, even more horrific, Japanese “soldiers” would go around Manila looking for young women for sex, when the girl refused, the entire family was tied up in their house and was then set on fire. In Lipa, 400 villagers were executed and the bodies dumped in the village well. At the San Fernando cemetery, US POW’s were forced to dig their own graves, the POW’s were then ordered to kneel down at the grave and then were beheaded. Thrown in the grave….I could go on and on….all these cruelties the Japanese are responsible for, and not just in the Philippines is why I have NO sympathy for last 8-10 months of the war with the US carpet bombing Japan, the sustained air offensive and the atomic attacks were payback for Japan’s swath of terror and theft and expansionism that killed 10 million and for the 138,000 allied POW’s that never returned from Jap prison camps…

Hi Woody, The actions of Japanese during WW2 are often staggeringly horrifying to me. I think it’s important that people know and remember and learn from this history — so that, hopefully, we will not have to relive such atrocities. WW2 is also a passion of mine. Some day I, too, hope to visit Luzon and see all the places I’ve been researching the past couple of years. I am envious of you. This particular article is part of my great-grandfather Alma Salm’s memoir. He was a POW on Corregidor and then at Cabanatuan. He wrote his memoir when he returned home. I’m slowing publishing that memoir — with explanations of historic context and pictures that I find. I’m also researching the lives of the POWs he mentions, then sharing their stories. As time goes on, their stories are being forgotten, and I hope to not let that happen. Thanks for reaching out.

My namesake uncle, Hubert Grabski, was taken with the fall of Corregidor. His journey took him to Bilibid, Cabanatuan, Mukden and finally Kamioka. (He was one of the Mukden 150 prisoners that were transfered to the lead mines for sabotage.) He never made it home as his repatriation flight crashed in Formosa enroute to Nichols Field killing all aboard.

Bert, thank you for sharing about your uncle. How tragic that he would have survived ALL of that, and then perish in a plane crash.